Radio Bristol’s “The Root of It” is a series connecting today’s influential musicians to often lesser known and sometimes obscure musicians of the early commercial recording era. The sounds and musicians we hear today on platforms like Radio Bristol can often be traced back to the sounds of earlier generations. What better way to discover these connections than to talk to the musicians themselves about some of the artists that have been integral in shaping their music? These influences, though generally not household names, continue to inspire those who dig deep to listen through the scratches and noise of old 78s, field recordings, and more, finding nuances and surprises that inevitably lead them on their own unique musical journeys.

For this installment of “The Root of It,” we spoke with legendary old-time musician Bruce Molsky. He spent much of his early life traveling through Appalachia learning knee-to-knee from legendary musicians and masters of various regional styles who are now long gone. Though Molsky’s music has undoubtedly been shaped by those important encounters, he has never been limited by specific regional music traditions; instead he has been able to develop his own unique style of playing helping to further traditions that are influencing generations of musicians that now follow in his footsteps.

Though best known for his mastery of the fiddle and banjo, Molsky began his career as a guitar player. His latest project Everywhere You Go captures his musical journey through guitar, highlighting some of the instrument’s innovators and those that have served as inspiration to his playing. Molsky was kind enough to share some thoughts with Radio Bristol about a musician who has inspired him throughout the years – guitar virtuoso Joseph Spence.

Bruce Molsky: Bronx-born, self-described “street kid,” now a legendary old-time musician.

Credit: Michael O’Neal

Bruce Molsky:

The early 1970s was a very strong time for all kinds of folk music around Ithaca, New York. After a summer of work as a hand on a dairy farm, I settled into a job washing dishes in Ithaca’s Collegetown at Johnny’s Big Red Grill, the epicenter of jamming and gatherings many nights of the week. A musically hungry 18 year old, I just wanted to be around some of the great players who were regulars there. Sitting across the table from Howie Bursen made me want to play the banjo. Likewise, the great guitarist John Miller was there, and used to play “The Titanic,” kind of a poignant mainstay – “It was midnight on the sea, the band was playing ‘Nearer my god to thee…’”

Guitar was my only instrument at that time, and somewhere in that (now fuzzy) overwhelming miasma of styles and people, a copy of the LP The Real Bahamas came into view. It was Joseph Spence and his wife Edith Pindar, along with others in their community, singing God’s praise and about other things, too. We sang the last track over and over, “I Bid You Goodnight,” a most beautiful call-and-response song usually reserved for funerals. Spence’s guitar playing there was heavenly, like a full calypso band all on one instrument, with all the moving bass lines and gospel chord movement. And the RHYTHM of it all! My god, you just conjure the ocean listening to “Out on the rolling sea, Jesus speak to me.” As culturally foreign as it was for me, it took a deep hold. Spence’s unique and utterly brilliant musical voice still floats in and hovers around my own guitar playing. I only wish I had had the chance to meet him and watch him play.

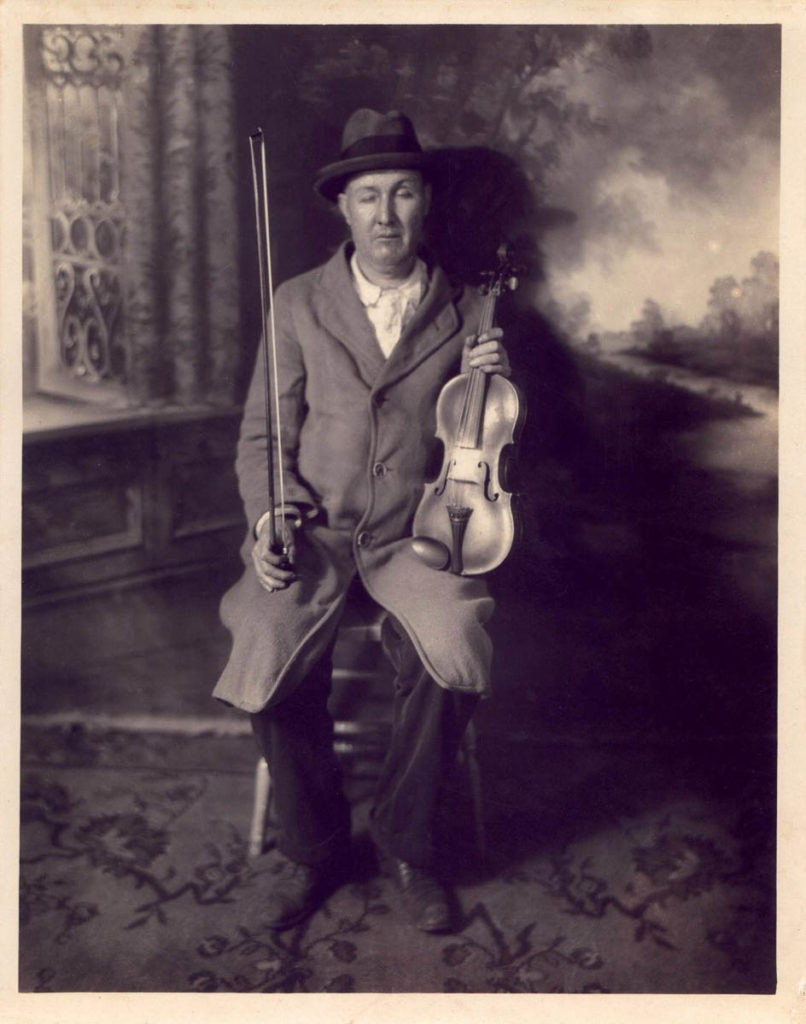

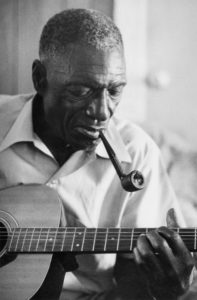

Joseph Spence was a unique Bahamian guitarist and singer who was hugely influential though his recordings are somewhat obscure. Source: This photograph was taken by A. R. Danberg, and a copy can be found in the Ralph Rinzler Archives of the Smithsonian Institution

Thankfully Spence was recorded on several occasions, including the aforementioned The Real Bahamas by Jody Stecher and Pete Siegel around 1968. But I believe it was Sam Charters who put out the first Spence recordings in the late 1950s on a Folkways LP. Once I had that one in my clutches, I learned several of the pieces (and later recorded “Bimini Gal”). Spence’s music was so open and straightforward that I thought if I tried hard enough, I could maybe crawl inside his head somehow and feel what he was feeling when he played, feel his vibe, with that pipe between his teeth and a jaunty hat on his head. Of course, that was not to be. But that feeling of simple beauty and rhythmic pulse stuck. Fifty years later, I still listen to those recordings for a spiritual pick-me-up and a personal trip back in time.

Smithsonian Folkways very recently released some up-to-now unpublished Spence recordings on a CD titled Encore. It’s a great addition to an already really interesting discography. And if you search on YouTube, you can find Spence’s utterly crazy rendition of “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town.”

Just be forewarned: once you’ve heard Joseph Spence, you can’t un-hear him. That was one of the best musical things that ever happened to me.

Molsky performing “Boogie Woogie Dance,” a song adapted from Tampa Red’s original tune.

To check out Molsky’s latest project Everywhere You Go or to find his latest tour dates, visit www.brucemolsky.com. Look for Molsky touring in various acts, including Molsky’s Mountain Drifters, Bruce Molsky and Tony Trischka, and as a solo performer.

Everywhere You Go, Bruce Molsky’s latest project, highlights his love of the guitar, which was also his first instrument.

* Radio Bristol would like to thank Bruce for sharing with us some of the sounds that have helped to shape his inspiring musical journey. Radio Bristol Program Director Kris Truelsen worked with Molsky to create this blog post. Kris also performs in the band Bill and the Belles.