If there are two things you might think would never go together, they would be Country Music and Disney Theme Parks. Well, since 1971, Country Music has been present in both The Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, and, since 1972, at Disneyland California, though the one in California closed in 2001. And now, for a short time, there will be an absence of Country Music at the Magic Kingdom as Grizzly Hall, home of the Country Bear Jamboree and the place to go to hear Country Music at the most magical place in the world, has closed its doors as it goes under a refurbishment. When Grizzly Hall opens back, the much enjoyed songs from the past 53 years will no longer be heard, and instead, guests will hear their favorite bears singing their favorite Disney songs in a Countryfied way.

Now, by this point, you are probably wondering why this strange attraction of singing bears at a Disney theme park is even remotely relative or how it even has ties to the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Well, when you have a show full of singing animatronic bears, you’ve got to have someone as the voice behind the machine. The show was originally developed not long before Walt Disney passed away. It was in the early days of his “Florida Project,” and Walt also wanted to build a Ski Resort in Northern California. At this resort, he wanted a show with animatronics made up of wildlife animals as the main cast, such as you see in The Enchanted Tiki Room. Walt recruited Imagineer Marc Davis to help with this project and put him in charge. Davis brought in Al Bertino to help, and together, they created the idea of a Mariachi Band of Bears, a Marching Band of Bears, Dixieland Bears, and more. Davis and Bertino eventually decided that the bears needed to have a “Country Twang” about them. Sadly, Walt passed away before he could see the Ski Resort, the bears, and the Florida Project come to fruition. Out of the three, only two made it past the drawing boards.

Davis and Bertino found a way for the bears and their show to live on. They decided that with the Florida Project still going strong, the bears would find a home there, and they did. All twenty-one of the wildlife critters found their way home to Grizzly Hall, where they would croon and serenade guests daily. But Davis and Bertino still needed someone to bring these bears to life, and they found the perfect group of people. A good majority of the bears and critters are voiced by The Stoneman Family. And while it has neither been confirmed nor denied, the bear named Ernest may or may not have been named after Pop Stoneman himself (I’ll just let myself keep believing that it is until someone tells me otherwise). Unfortunately, the Stonemans never received proper accreditation to lend their voices to the bears, but, Roni Stoneman herself once told me about the experience of recording the original songs with her sister Patsy and their father. She even sang my favorite song from the show to me! I also learned that the Stoneman family were not the only Country Music artists involved with the show. Many other country music artists also lent their voices to these loveable bears, such as Tex Ritter and Cheryl Poole. In 2002, the bears hit the silver screen, and though none of the songs from the show at the Magic Kingdom made their way into the film, other famous musicians such as Willie Nelson, Bonnie Raitt, Elton John, and Wyclef Jean made cameos in the film.

Grizzly Hall is now temporarily under refurbishment as the bears are planning a new show for their fans. At Disney’s D23 Expo in September 2023, they announced that when Grizzly Hall re-opens, the new show will include all the sounds of Nashville as the bears bring on their interpretation of classic Disney songs such as The Bare Necessities. Guests will see these classics played in many different country sub-genres, including bluegrass and Americana. And though there will be plenty of references to the original show, the songs will be gone, though there may be room for a beloved song from the original show (my bets on Big Al coming in singing Blood on the Saddle). And while I will miss the original show, I am excited to see how Disney reincorporates Country Music into their shows once again. Maybe we’ll hear a bit of my favorite yodeling cowboys, Riders in the Sky, singing some of my favorite songs from Toy Story and other PIXAR tunes. If you find yourself at the Magic Kingdom after Grizzly Hall reopens, be sure to find your way there and watch the show, and then maybe grab you something good to eat next door at Pecos Bills. I can guarantee you will have a good time and a good laugh. Y’all come back now, ya hear?

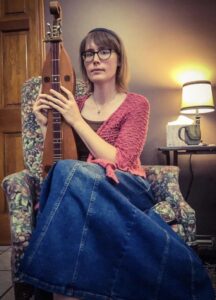

About the author: Myrissa Pierce is the Assistant Museum Manager and Volunteer Coordinator at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum. She’s also a full time Graduate Student at The University of Oklahoma (Boomer Sooner!), and loves all things Disney, Marvel, Anime, Taylor Swift, music, her dog, and her four cats.

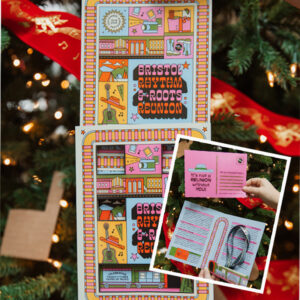

The Live performances are the main attraction at Bristol Rhythm and Roots Reunion, there is something for everyone. This year’s artist lineup consists of some big names such as

The Live performances are the main attraction at Bristol Rhythm and Roots Reunion, there is something for everyone. This year’s artist lineup consists of some big names such as  Some of my favorite things about the festival are not necessarily going to all the live performances with my friends but everything else Bristol Rhythm has to offer also. Bristol Rhythm has so much more to offer than the live performances. Some of my favorite things to do at the festival other than the live performances consists of walking the streets and seeing downtown Bristol decorated for the festival, hanging out with friends at Cumberland Square Park, stopping by all the food trucks and trying new food, making new friends, and shopping on the streets of downtown just to name a few things. Although I am not of age anymore to participate in Children’s Day I still have very fond memories of the event. Children’s Day is held on Sunday in Anderson Park from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.. There you can expect to see food trucks, arts and crafts, and live entertainment. For more information on Children’s Day you can click

Some of my favorite things about the festival are not necessarily going to all the live performances with my friends but everything else Bristol Rhythm has to offer also. Bristol Rhythm has so much more to offer than the live performances. Some of my favorite things to do at the festival other than the live performances consists of walking the streets and seeing downtown Bristol decorated for the festival, hanging out with friends at Cumberland Square Park, stopping by all the food trucks and trying new food, making new friends, and shopping on the streets of downtown just to name a few things. Although I am not of age anymore to participate in Children’s Day I still have very fond memories of the event. Children’s Day is held on Sunday in Anderson Park from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.. There you can expect to see food trucks, arts and crafts, and live entertainment. For more information on Children’s Day you can click