By Julia Underkoffler, Collection Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum

Happy spooky season! This time of year, many people seek out ghost tours and other spooky adventures, many of which take place in cemeteries. People who visit cemeteries for specific or unique tombstones are called “tombstone tourists.” But did you know you can also learn a lot about history in a cemetery?

Originally founded by Jim Tipton in 1995 to document where famous people were buried, Find a Grave soon opened up to allow a passionate online community to document, recover, and preserve the history held in cemeteries worldwide. Over 250 million graves have now been documented. Anyone can create an account to contribute to this open resource! You can also build “virtual cemeteries” with collections of gravesites from different cemeteries. I have done one for my ancestors on both sides of my family tree and one for the 1927 Bristol Sessions!

So far, there are 43 members in the Bristol Sessions Virtual Cemetery and graves in 7 different states – Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, Mississippi, New Mexico, and California. As you explore the cemetery, you will notice that most of the artist’s gravestones are not particularly ornate; they are just simple markers, and some are not marked at all. Now, let’s explore exactly where the session artists are buried!

- Ralph Peer

- Buried next to his wife Monique, who accompanied him on his Bristol Sessions trip, in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California.

- Ernest “Pop” Stoneman and his wife Hattie

- Buried together in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Nashville, Tennessee. Five of their fourteen children are also buried there (Patsy, Scotty, Oscar “Jimmy,”Roni, and Van Haden).

- The Stonemans invited nine of their friends and family members to record with them at the Bristol Sessions.

- Pop Stoneman’s older brother George Stoneman

- Buried in McKenzie Cemetery in Grayson County, Virginia.

- Hattie’s twin siblings Bolen and Irma Frost

- Buried in Ballard Cemetery in Galax, Virginia.

- Kahle and Edna Brewer

- Buried in Felts Memorial Cemetery in Galax, Virginia.

- Iver Edwards

- Buried in Monta Vista Gardens in Galax, Virginia.

- Pop Stoneman’s older brother George Stoneman

- Alexander “Uncle Eck” Dunford

- Buried in Old Quaker Cemetery in Pipers Gap, Virginia

- Ernest Phipps and his Holiness Quartet all stayed near Corbin, Kentucky, and are buried within a four-mile radius of each other.

- Ernest Phipps and A. G. Baker

- Buried in Pine Hill Cemetery in Corbin, Kentucky.

- Rolan Johnson

- Buried in Felts Chapel Cemetery in Corbin, Kentucky.

- Ancil McVay

- Buried in Rest Haven Cemetery in Corbin, Kentucky.

- Ernest Phipps and A. G. Baker

- John Preston (J.P.) Nester

- Buried in Cruise Cemetery in Hillsville, Virginia.

- Norman Edmonds

- Buried in Gardner Memorial Cemetery in Hillsville, Virginia.

- The Bull Mountain Moonshiners

- Charles M. McReynolds, the grandfather of Jim and Jesse McReynolds

- Buried in Hazelton Stallard Cemetery in Coeburn, Virginia.

- William McReynolds

- Buried in Hazelton Stallard Cemetery in Coeburn, Virginia.

- Howard Greear

- Buried in the Greear Family Cemetery in Flatwoods, Virginia.

- Charles Greear

- Buried in Greenwood Memorial Gardens located in Coeburn, Virginia.

- Bill Deane.

- The only member of the Bull Mountain Moonshiners I have not yet been able to find is Bill Deane.

- Charles M. McReynolds, the grandfather of Jim and Jesse McReynolds

- The Carter Family,

- Alvin Pleasant Carter, and his wife, Sarah

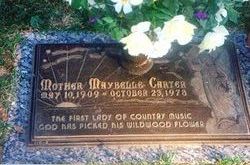

- Sarah’s cousin, Maybelle Carter

- Buried in Hendersonville Memory Gardens in Hendersonville, Tennessee, next to her husband (and A.P.’s cousin) Ezra. Their three girls, Helen, June, and Anita, are buried there as well. And yes, June is buried next to Johnny Cash.

- Two members of The Alcoa Quartet are buried in cemeteries that are about five miles from each other. I have been unable to identify stones for the other two members, the brothers John Edgar and James Herbert Thomas.

- William Burrell Hitch

- Buried in Mount Lebanon Cemetery in Maryville, Tennessee

- John Leonard “Lennie” Wells.

- Buried in Grandview Cemetery in Maryville, Tennessee.

- William Burrell Hitch

- The Shelor Family stayed in the Meadows of Dan area and were buried in cemeteries about three miles from each other.

- Joe Blackard

- Buried in the Joseph Blackard Cemetery in Meadows of Dan, Virginia.

- Joe’s daughter Clarice, her husband Jesse, and Jesse’s brother Pyrhus are all buried in the Meadows of Dan Baptist Church Cemetery in Meadows of Dan, Virginia.

- Joe Blackard

- Couple James Whiley and Flora Baker are buried in Baker Cemetery in Dungannon, Virginia.

- Red Snodgrass and His Alabamians

- Thomas P. Snodgrass and his brother Ralph Campbell Snodgrass are buried in Sunset Memorial Park in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

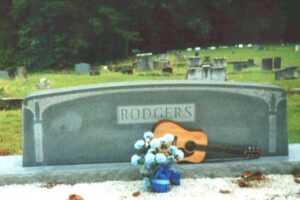

- Jimmie Rodgers

- Buried in Oak Grove Baptist Church Cemetery in Meridian, Mississippi.

- Tenneva Ramblers

- I believe I have found Jack Pierce (Shelby Hills Cemetery) and Claude Slagle (East Hill Cemetery) in Bristol, Tennessee. However, I have not yet been able to locate Jack’s brother Claude or James “Jack” Grant. Except for Jimmy Rodgers, The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers (soon to be called the Tenneva Ramblers) were all from Bristol. A chance visit to their hometown gave this Asheville-based band an opportunity to audition for the Bristol Sessions.

- The West Virginia Coon Hunters

- Wesley’ Bane’ Boles

- Buried in Zion United Methodist Church Cemetery in Nebo, Virginia, and his place of rest is unmarked.

- Vernal Vest

- Buried in Trail Cemetery in Princeton, West Virginia.

- Clyde S. Meadows

- Buried in Big Run Cemetery in Diana, West Virginia.

- It is not easy to say for sure where Joe Stephens and Fred Belcher have been laid to rest. Several possible locations have been identified, but with no birth or death dates to go off of, we can’t say for certain.

- Wesley’ Bane’ Boles

- The Tennessee Mountaineers was a church group of around twenty people from Bluff City, Tennessee. Here is where three of the members I have identified so far are buried:

- Roy Hobbs, the brother-in-law of A. P. Carter

- Buried in Blue Ridge Memorial Gardens in Roanoke, Virginia.

- Father and daughter duo George and Georgia Massengill (Warren). At 12 years old, Georgia was the youngest participant in the sessions and the only one still alive when the museum opened in 2014.

- Buried in Morrell Cemetery in Bluff City, Tennessee.

- Roy Hobbs, the brother-in-law of A. P. Carter

- Blind Alfred Reed

- Buried in Elgood Cemetery in Elgood, Virginia.

- B. F. Shelton

- Buried in Corinth Cemetery in Corbin, Kentucky.

- Alfred Karnes

- Buried in McHargue Cemetery in Lily, Kentucky.

- Henry Whitter

- No stones have been found using what we believe are Whitter’s birth and death dates. However, it is not uncommon for the dates on older graves to be slightly off, and this stone, located in Eden Cemetery in Summerset, Kentucky, is assumed to be Whitter’s most likely resting place.

Lastly, there are five artists – Walter Mooney, Tom Leonard, Paul Johnson, Charles Johnson, and El Watson – whom we know virtually nothing about beyond their names and that they played at the Bristol Sessions. Hopefully we will find their final resting places one day as we continue to research.

I have always had an interest in cemeteries, the artistry behind making gravestones, and the preservation of them. I even decided to write my master’s thesis on the similarities between public history practices and cemeteries! Creating a virtual cemetery for the Bristol Sessions artists was a passion project that allowed me to view the content of the museum where I work through my favorite historical lens and it doesn’t stop here! If you are interested in exploring more virtual cemeteries, check out the other two I have made: BCM VIPs – people who have carried on the musical tradition and innovated the sounds of Bluegrass, Country, and American, and Women in Old-Time – a special cemetery dedicated to the women who were featured in our special exhibit, I’ve Endured: Women In Old Time Music, which is now traveling. All of these virtual cemeteries are updated regularly as I continue to research, so stay tuned for more!