Today is the anniversary of Jimmie Rodgers’ passing on May 26, 1933, and therefore we wanted to celebrate him with this blog post by volunteer Ed Hagen – including a short lesson in Rodgers’ iconic guitar style! Ed moved to Bristol last summer, and he soon joined us at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum as a Gallery Assistant. He has played guitar for many years, mostly jazz, but he has been working hard on the rudiments of country and bluegrass since moving to Tennessee. As Ed says, “There is no better place to start than with the guitar style of Jimmie Rodgers!”

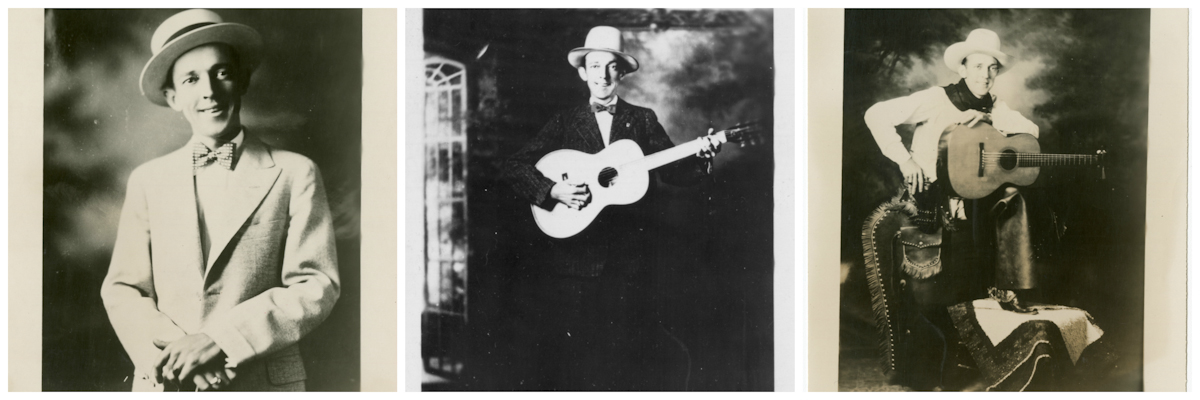

Jimmie Rodgers

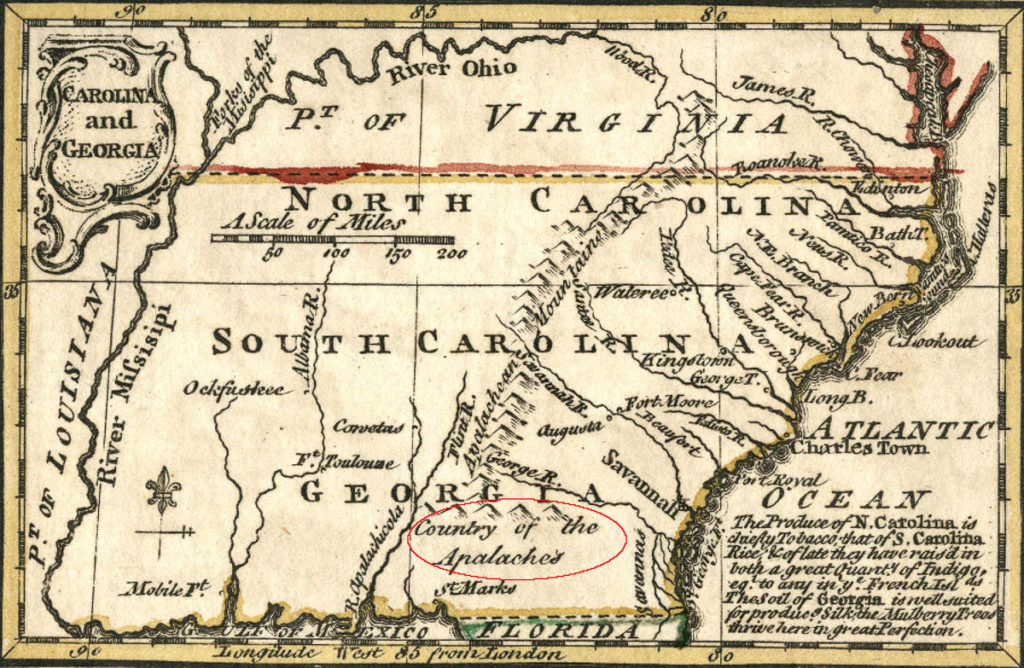

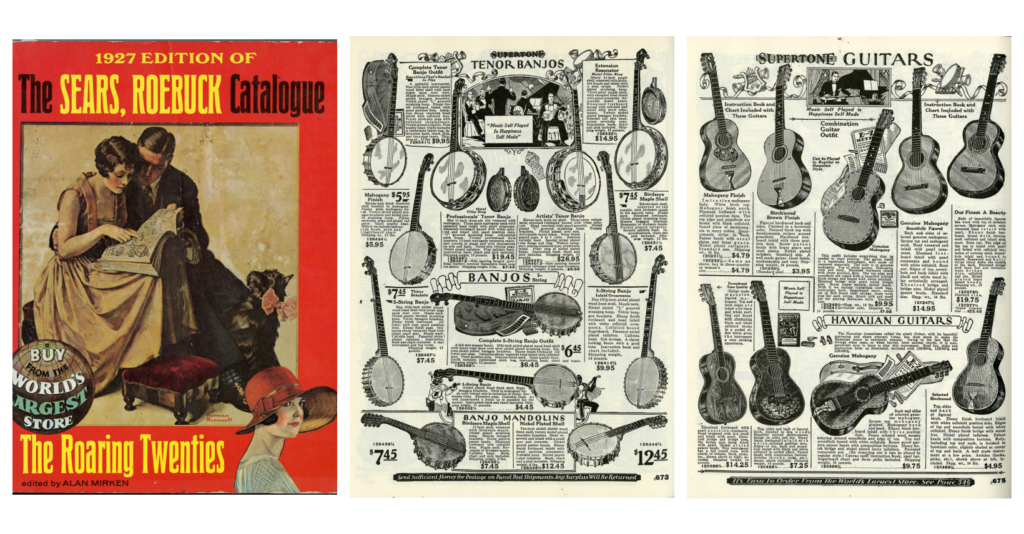

Jimmie Rodgers was born in 1897 in Meridian, Mississippi, and he learned to play guitar while working on the railroad as a water boy and brakeman. He was influenced by the music played and the songs sung by the African American railway workers he met at the railway yard and around town – their call-and-response singing style during work and the blues songs they sang made a distinctive mark on Rodgers’ sound. He also spent time in Meridian’s opera house, vaudeville theaters, and hotels where he heard jazz, parlor music, and popular tunes, all of which also provided inspiration.

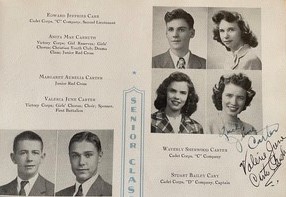

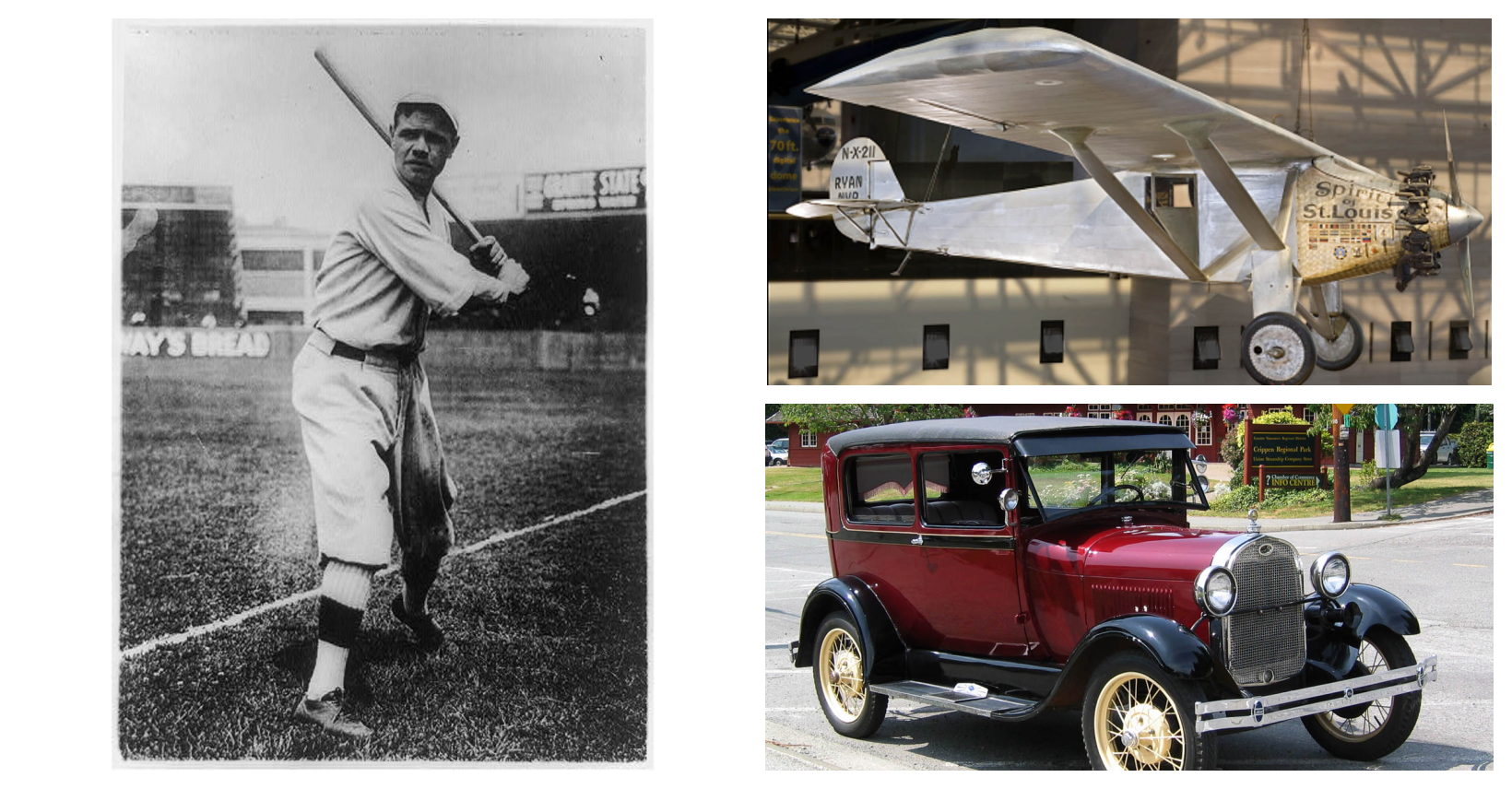

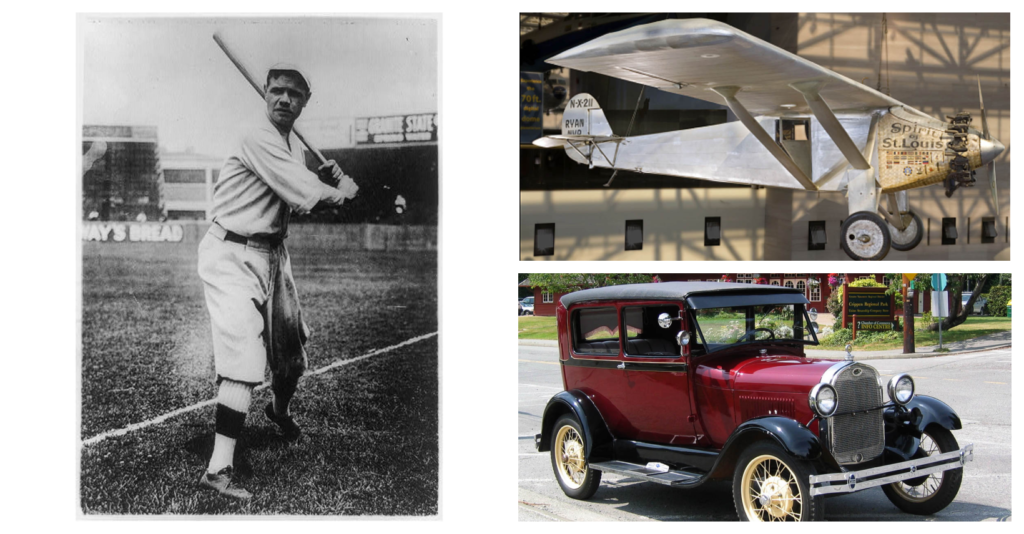

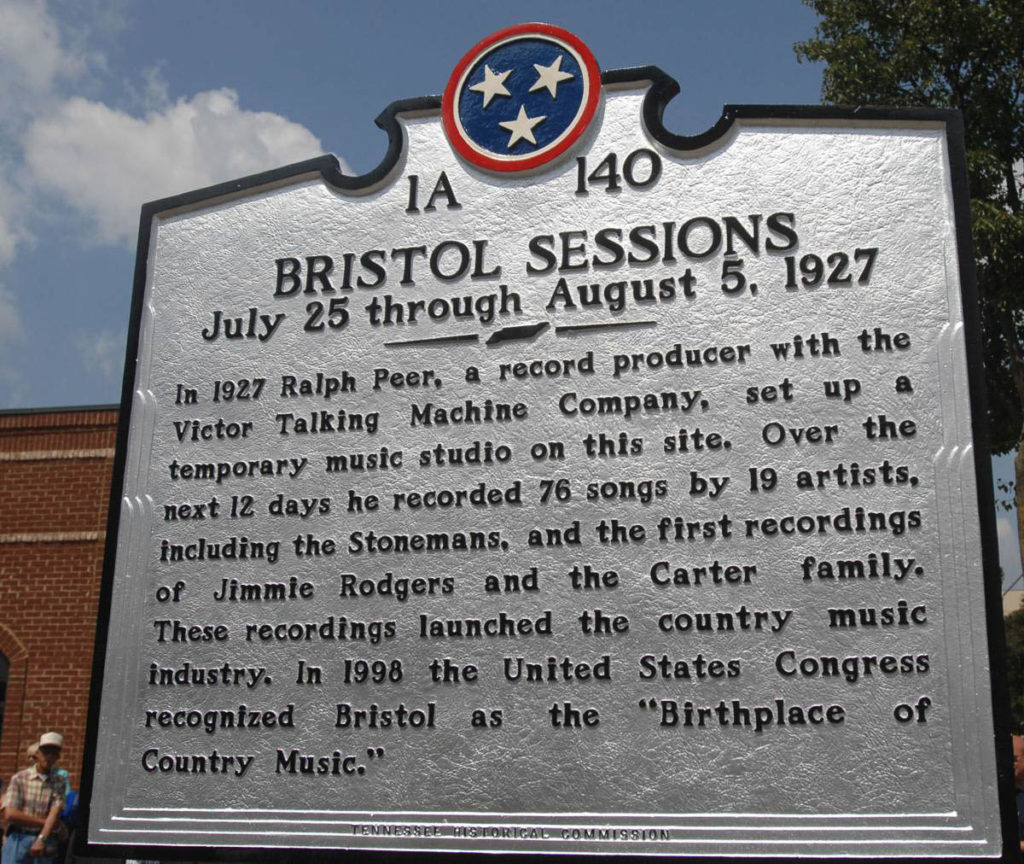

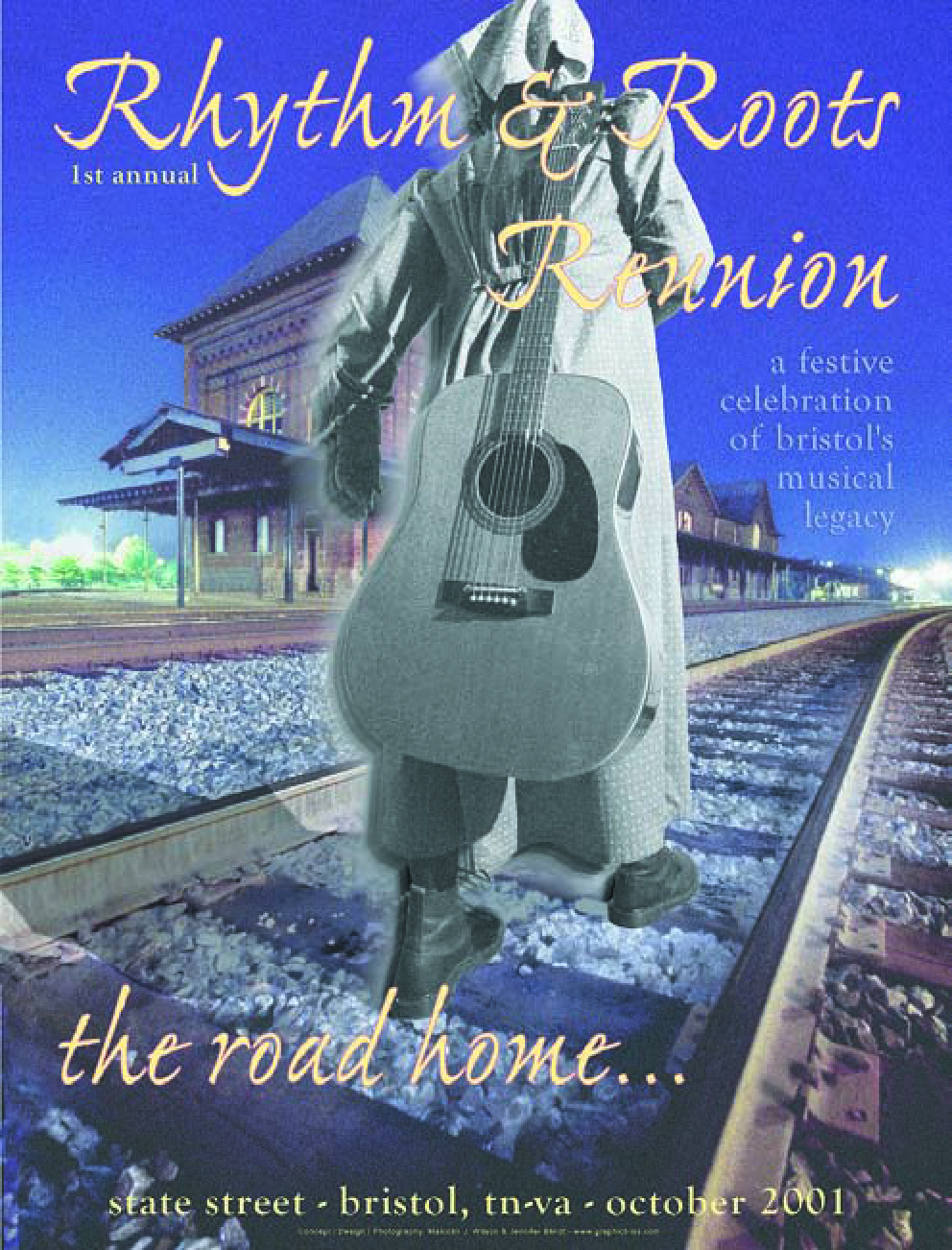

In 1927 he moved to Ashville, North Carolina, where he started playing on the local radio station with a small band made up of three musicians from Bristol, Tennessee-Virginia. Later that year they heard about recording sessions that were going to be held in Bristol conducted by the Victor Talking Machine Company, and so they traveled up to audition. These were the famous “1927 Bristol Sessions” that we celebrate at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum today. After arriving in Bristol for their audition, Rodgers and the band ended up recording separately, with speculation attributing this to an internal squabble or a change made by producer Ralph Peer. For Rodgers, this led to a recording contract and huge success as a recording and performing artist – though for only six short years before his death from tuberculosis in 1933 – and he is now celebrated as the “Father of Country Music.”

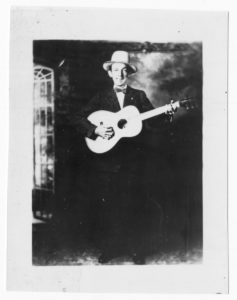

Promotional portrait of Jimmie Rodgers. From the John Edwards Memorial Foundation Records, #20001, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Jimmie’s Guitar Style

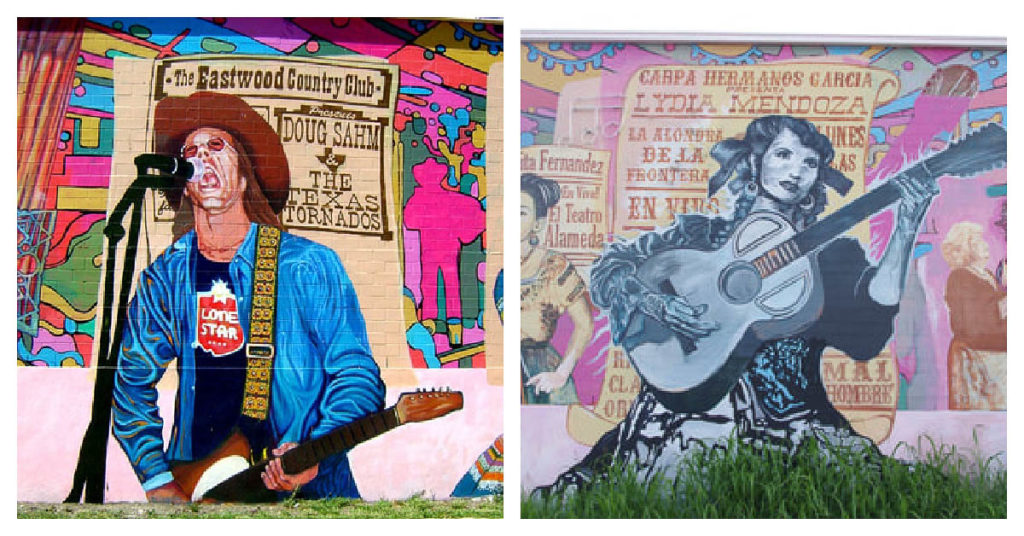

Jimmie Rodgers’ guitar style is iconic and made a huge impact on country music musicians and beyond – numerous artists have copied and embellished it for their own music playing throughout the years. It is based within a traditional style of guitar playing, but he is one of the most successful and well-known performing and recording artists to play in this style, and he certainly knew how to make it his own!

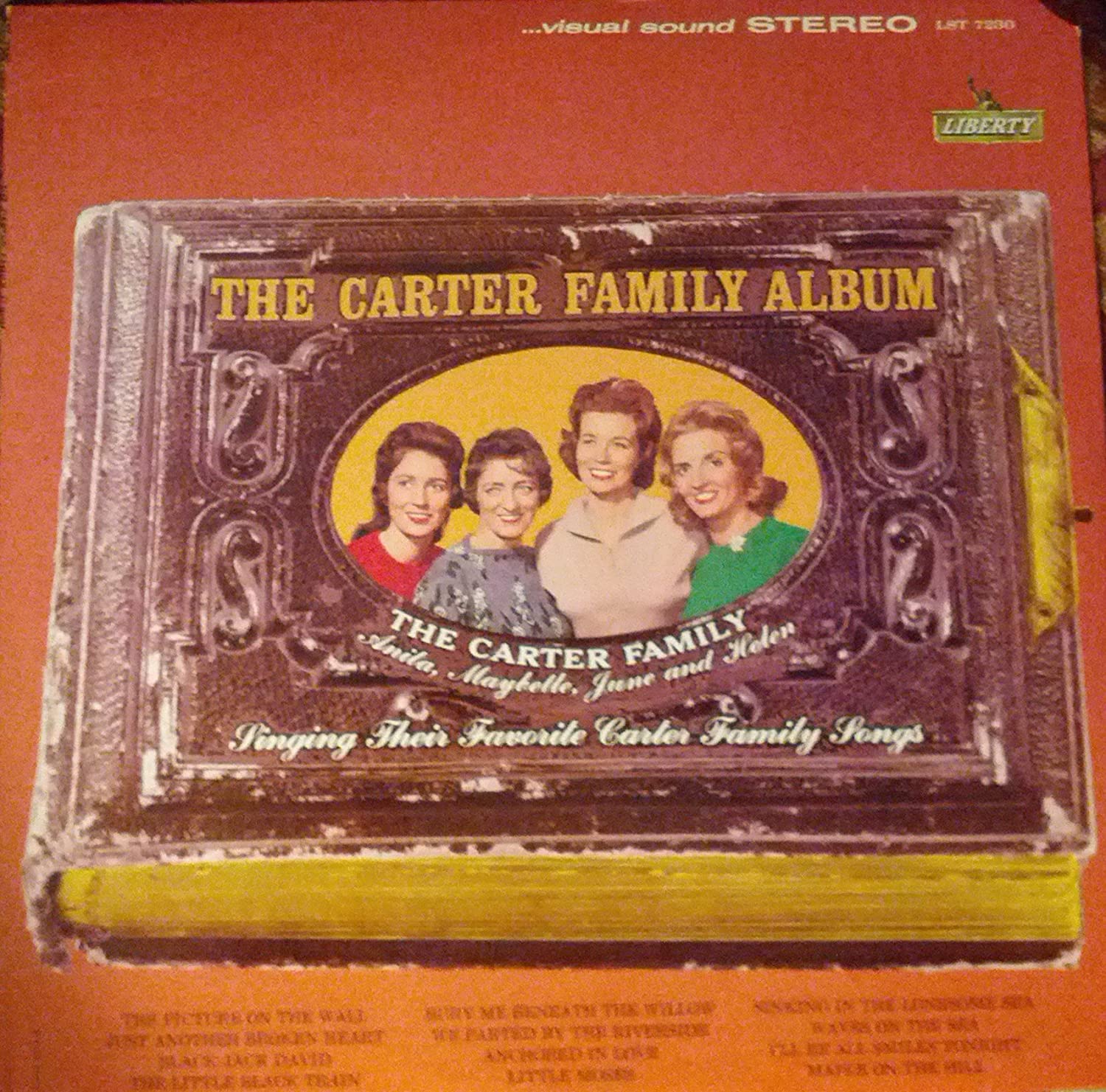

For guitar players, it’s a great style to learn because it is so versatile. As the bartender in the Blues Brothers would put it, the style works for both kinds of music, country and western. You can slow it down for a Hank Williams’ ballad, or swing it hard for a Bob Wills’ two-step. You can use it to play Gene Autry cowboy tunes or just about any Merle Haggard or Buck Owens tune. And once you master it, the style gives you the foundation to play the related but more challenging guitar styles of Maybelle Carter, Merle Travis, and Chet Atkins.

Playing Guitar Jimmie Rodgers-Style

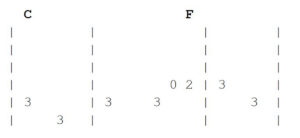

Before we can play this guitar style, we need to begin with short introduction on how to play traditional country bass, because that is the foundation of the style. For the most part, traditional country bass players play the root note of the chord on the first beat of the measure, and the fifth note of the chord’s major scale on the third beat. The fifth can either be played above or below the root. Playing behind a C chord, these notes would be C and G. This is called playing “one five.”

A triplet (that is, three notes played where a quarter note would ordinarily be played) can be played on the fourth beat of a measure, especially before a chord change. This triplet anticipates the chord that is played in the next measure, either ascending or descending to the root of the target chord. The three notes in the triplet are the three tones just above or below the root of the target chord. For example, if ascending from a measure of C to a measure of F, the triplet at the end of the C measure would be the fifth, sixth, and seventh tones of the F major scale.

If descending from a C measure to a G measure, the notes of the triplet would be the fourth, third and second tones of the G major scale.

Alternatively, a bass player will sometimes play a third on the third beat, especially if that note is a seventh of the target chord (the chord to be played in the next measure). If moving from a C to an F, for example, the third in C (E) is the seventh in F. Or sometimes, just to keep it simple, the bass player will play the root on the third beat.

Rodgers does all of this on the guitar rather than on a bass. He plays a bass line on his guitar by fingering a first-position chord with his left hand, which will typically have the first and fifth notes of the major scale on the bottom three (EAD) strings. Just like any country bass player, he’ll “one five” it, playing the first and fifth tones on the first and third beats of the measure, mix in triplets, and occasionally drop in a root or third on the third beat. While doing this, he’ll strum the treble strings on the other beats. This allows him to effectively play bass and guitar at the same time.

This is sometimes called a “boom chuck” rhythm, similar to a military band’s “oom pah” or a stride piano player’s left hand. The “boom” is the bass note, and the “chuck” is the strum. Sometimes, to spice it up, a down-up strum is added to the chuck, creating a “boom chucka” (sometimes called a “church lick”). So the last beat of a measure might be a “chuck,” a church lick, or a triplet.

A brief note about the strum: These first position chords typically include open strings, and no particular effort is made to dampen them. It is not essential to play every string on every chord; the treble top notes (the B and E string) are often omitted.

There are no strict rules about any of this, except that it all has to done with confidence and a swing feel. You should be able to sing, play the bass and chords, and drop in a triplet or church lick as the mood strikes you. This all comes with practice.

The exercise below will get you used to playing ascending and descending triplets. Start slow and play it until it becomes second nature.

Providentially, Rodgers made The Singing Brakeman, a short sound film released in 1930 where he plays guitar and sings three songs, so you can see exactly how he plays. The film is available on YouTube. You’ll need to take one precaution if you are playing along with the video. The guitar in the film is tuned a half step high, so to play along you’ll have to tune your guitar up a half step or put a capo on the first fret. When we talk about these tunes below, we’ll do so as if the recording was in standard tuning, that is, when he fingers something that looks like a C chord in the film, we’ll call it that, even though we are hearing a C# chord on the soundtrack.

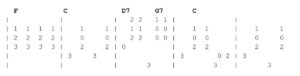

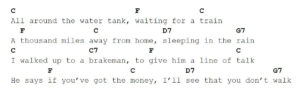

With all this in mind, let’s take a look at the first song in The Singing Brakeman, “Waiting on a Train.” Rodgers begins by imitating a train whistle, and then sings some nonsense syllables over this short guitar opening:

The partial F chords in the first bar are played as four simple down strokes on the four beats. The second bar is a boom chuck, playing the root instead of the fifth on the third beat. The third bar is two church licks. He ends the fourth bar as a triplet leading into the first bar of the chorus, which is played “one five.”

I’m not going to tab out the rest of the song. It goes against the spirit of how these songs are played. Players are free to sprinkle triplets and church licks wherever they like. Jimmie Rodgers likely never played the same song the same way twice. But to get you started, the chords for the first verse go like this:

This is just a start for aspiring Jimmie Rodgers-inspired players, but it should give you a good place to begin as you explore the wonderful musical world of “America’s Blue Yodeler,” “The Singing Brakeman,” and the “Father of Country Music”!

![The photograph show a display mannequin showcasing a grey t-shirt, red scarf, and musician brooch. The t-shirt has the word [app-uh-latch-uh] on it.](https://birthplaceofcountrymusic.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Appuhlatchuh-tee-768x1024.jpg)