Connections between the Hunger Games and Appalachian Traditions and Music in the Hunger Games

By Erika Barker, Curatorial Manager

Sometimes people discover new passions in unexpected places. The 2023 release of the movie adaptation of The Hunger Games: A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, is helping introduce new audiences to Appalachian culture and country music. Although it might be surprising that a dystopian young adult novel about children being forced to fight to the death could even loosely be based on real cultural and physical landscapes, this is not the first time a Hunger Games book has sparked a conversation about Appalachia.

The first Hunger Games book was released in 2008 and spent more than 100 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Since then, the series has been translated into 52 languages and sold over 100 million copies worldwide. The first three books have won a combined 77 literary awards with the film series grossing over $3.3 billion worldwide and is the 20th highest-grossing film franchise of all time. The books are about a totalitarian country that forces two teenagers from each of its subjugated districts to fight as tributes in a highly publicized battle to the death called the Hunger Games. The Hunger Games are an annual reminder of the Capitol’s power and the failed rebellion of previous generations from the districts. Although the series is fictional, through the popularity of these books, and their respective movies, a wider audience has been subtly introduced to some of the places, people, and music that makes Appalachia unique.

So, how does the Hunger Games make people think about Appalachia? Well, Suzanne Collins’s fictional country of Panem is set in North America at an unspecified date in the future after an apocalyptic event has left the continent with little resemblance to the Americas we know today. The country is divided into a Capitol and 13 districts. Each district has a distinctive export that symbolizes that region, such as luxury items, textiles, grain, livestock, fishing, or electronics. Katniss Everdeen, the protagonist of the original trilogy and Lucy Gray Baird, a protagonist in the prequel, A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes are both from District 12, a district centered around coal mining. These two characters give us a glimpse at the fictionalized traditions inspired by real Appalachian people. Here are just a few examples of real Appalachian music, landscape, and cultural connections found in the world of The Hunger Games.

Mining and southern stereotypes

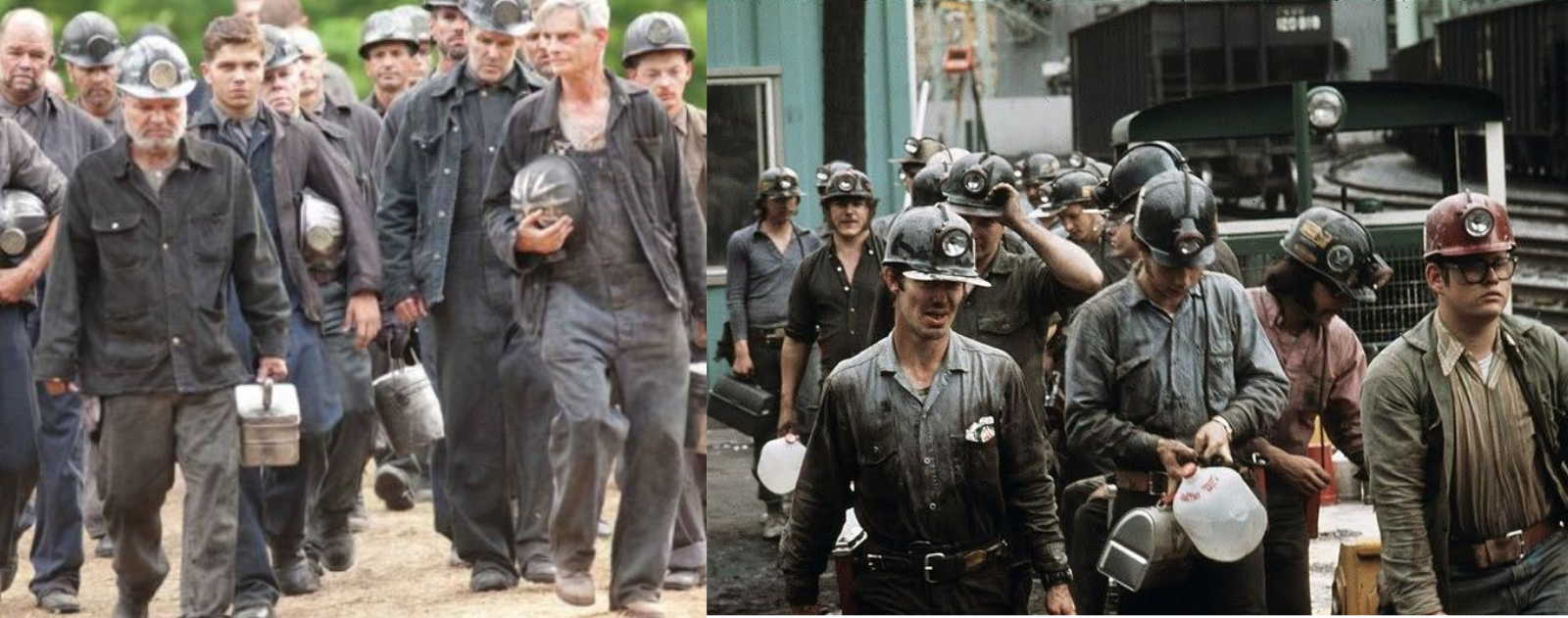

District 12 is based in the southern Appalachian region, an area that has historically produced and exported coal as a resource across the country. Several movie scenes were filmed in North Carolina where interested fans and movie buffs can visit those locations and experience the natural beauty of the region firsthand. Although Katniss and Lucy Gray both think fondly of the woods and natural landscapes of the district, they are not blind to the plight of the people living there.

District 12 is the poorest district, with industry centered on coal mining. Throughout all three Hunger Games books and the prequel, many citizens of Panem look down on District 12. Outsiders talk about the district in ways that resemble the real-life negative stereotypes often placed on the people of Appalachia.

In Appalachia, the coal industry has sustained mountain communities for over a century despite being a notoriously dangerous profession. In addition to being an intensely physically demanding job, occupational hazards such as collapses, explosions, accidents, and ailments like Black Lung disease have ensured coalfield communities are consistently among the least healthy. Oppressive business practices, like those portrayed in the Hunger Games reflected in the Capitol’s treatment of District 12, led to even worse living conditions and quality of life for coal miners and their families.

Beyond the surface-level similarities between the fictional and real-world regions, there is also a strong underlying similarity in the history of resilience and resistance found in the people of Appalachia. It is fitting that the location of the West Virginia Mine Wars was the inspiration for the birthplace of the girl who was brave enough to defy the Capitol with compassion and spark a revolution.

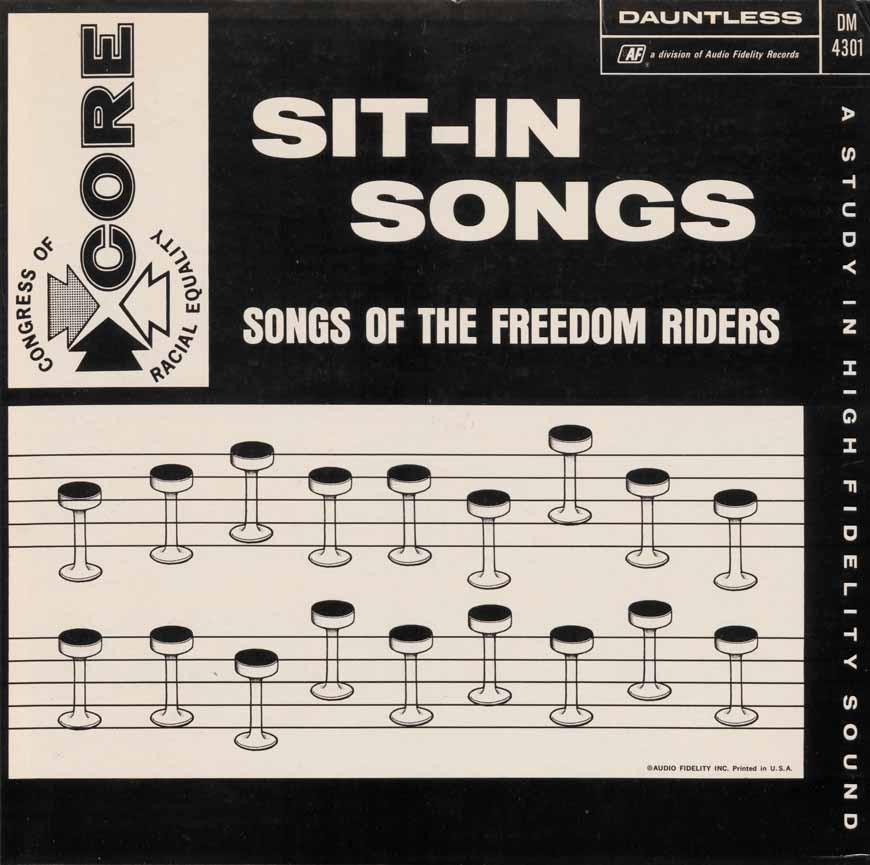

Protest Music

Appalachia has a strong tradition of turning current events, especially tragic events, into songs. In A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Lucy Gray Baird writes a song after witnessing a hanging. Lucy Gray’s “The Hanging Tree” is reminiscent of Florence Reece’s “Which Side Are You On,” which Reece wrote after a raid on her house during the Harlan Country Wars. The song became a popular protest song and has been used for many causes since. In the same way, Katniss Everdeen sings Lucy Gray’s “The Hanging Tree” over 60 years later, turning the tune into the anthem of a revolution. Just like how music reaches people on an emotional level, often inspiring them to action in the books, music has been used as an outlet for frustrations and a rallying cry for solutions throughout much of Appalachian’s history.

Video: Black Lung was written by Hazel Dickens about her brother’s struggle with the miner’s disease.

Balladry

Murder Ballads are one of the most popular forms of balladry in folk music today. Ballads are a narrative form of songwriting that tells a story, in this case, one of murder. The book, A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, is written in much the same way as a traditional murder ballad and explores many of the same themes commonly found within the genre. Murder ballads often expose the weakness of humanity in much the same way Coriolanus Snow realizes the brutality of hunger games in the books.

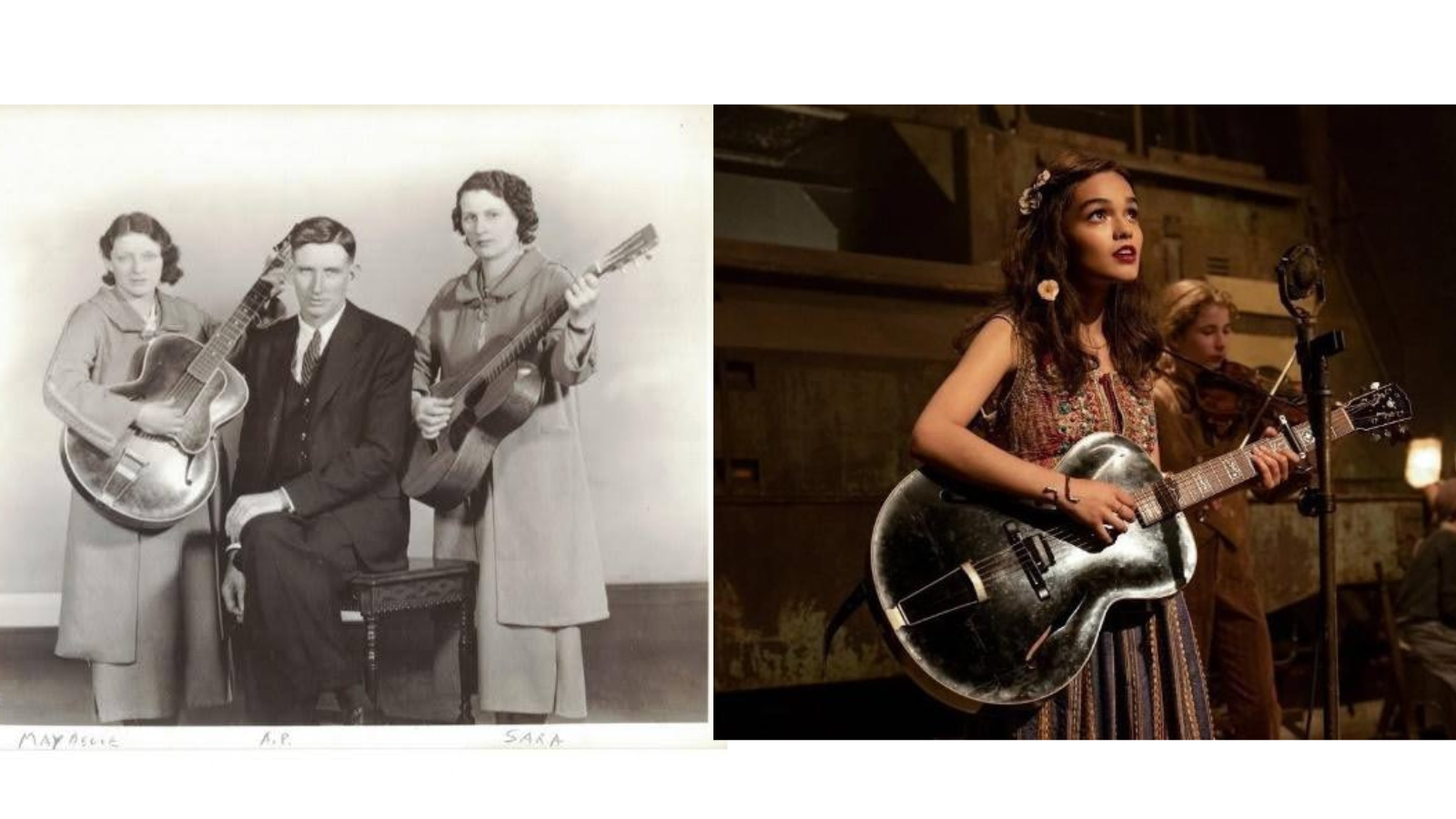

The Carter Family

The early country music scene of the 1920s and 1930s is easily spotted in the dance scenes at the Seam – referring to the most distressed area of district 12 – in A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes. Collins even pays homage to The Carter Family when Maude Ivory sings “Keep on The Sunny Side.” While many of the songs are inspired by the real music of Appalachia but written as originals for the books and movies, “Keep on the Sunny Side” is one of the few cover songs that make an appearance. Lucy Gray’s vintage Gibson L-10 guitar is another notable nod to the Carter Family. While Lucy Gray’s guitar may not be the exact same model, it is clear that an effort was made to match Mother Maybelle’s iconic guitar.

The soundtrack

Much like the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack from 2008, the 2023 soundtrack for A Ballad of Song Birds and Snakes is making waves and bringing new attention to country music styles. Many roots and Americana musicians are represented on the soundtrack including Billy Strings, Sierra Ferrell, Charles Wesley Godwin, Bella White. Molly Tuttle contributed her version of another Carter Family classic, “Bury Me Beneath the Willow,” which they first recorded at the 1927 Bristol Sessions! Tuttle also lends her guitar skills to the character of Lucy Gray. She and Dominick Leslie provided the guitar and mandolin parts for much of the film.

May the music be ever in your favor.

Erika Barker is the Curatorial Manager at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.