By Ed Hagen, volunteer gallery assistant and guest blogger at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

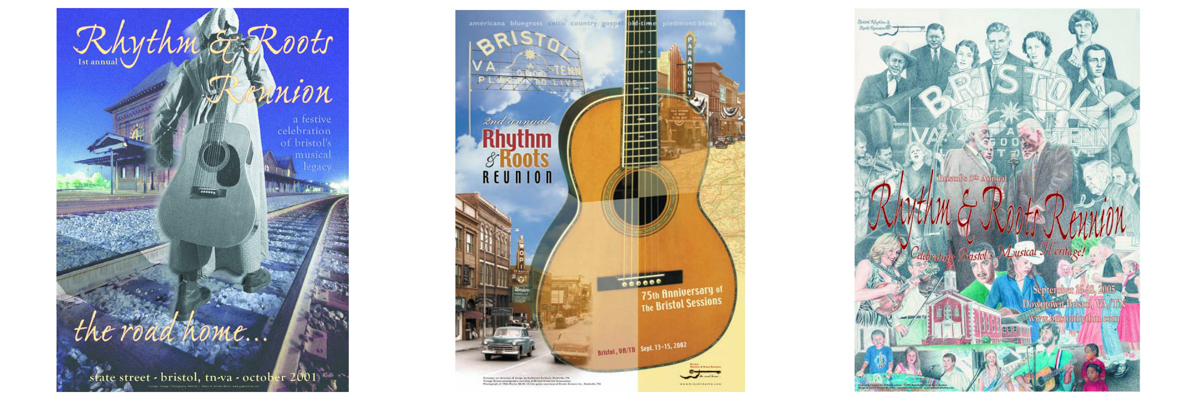

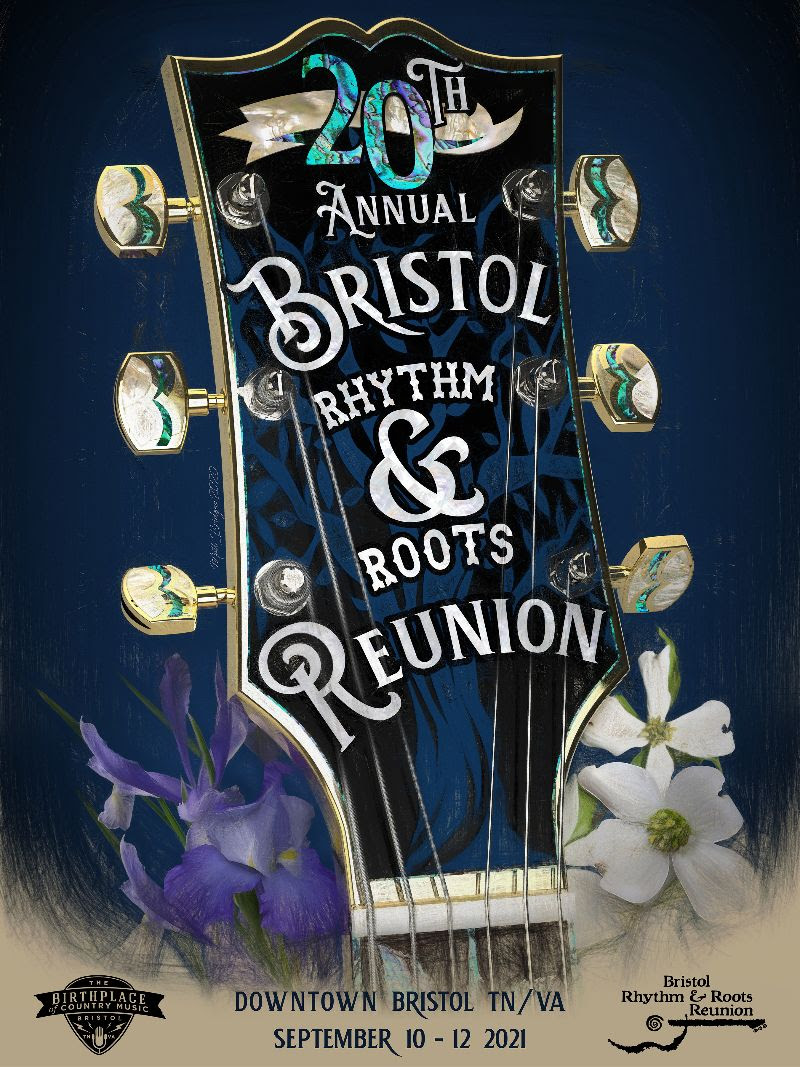

The Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol, Virginia celebrates Bristol’s rich musical heritage surrounding the 1927 Bristol Sessions, a series of recordings that launched the careers of the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers. With April being “International Guitar Month”, this two part blog post will take a deep dive into the guitars of these famous musicians and stories surrounding these instruments.

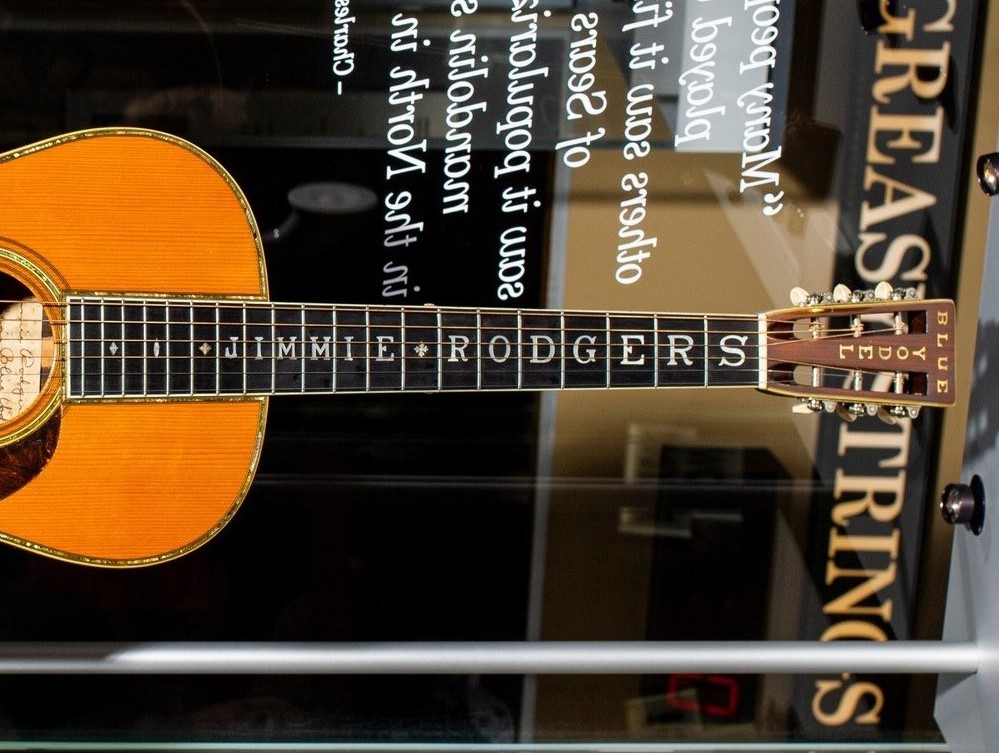

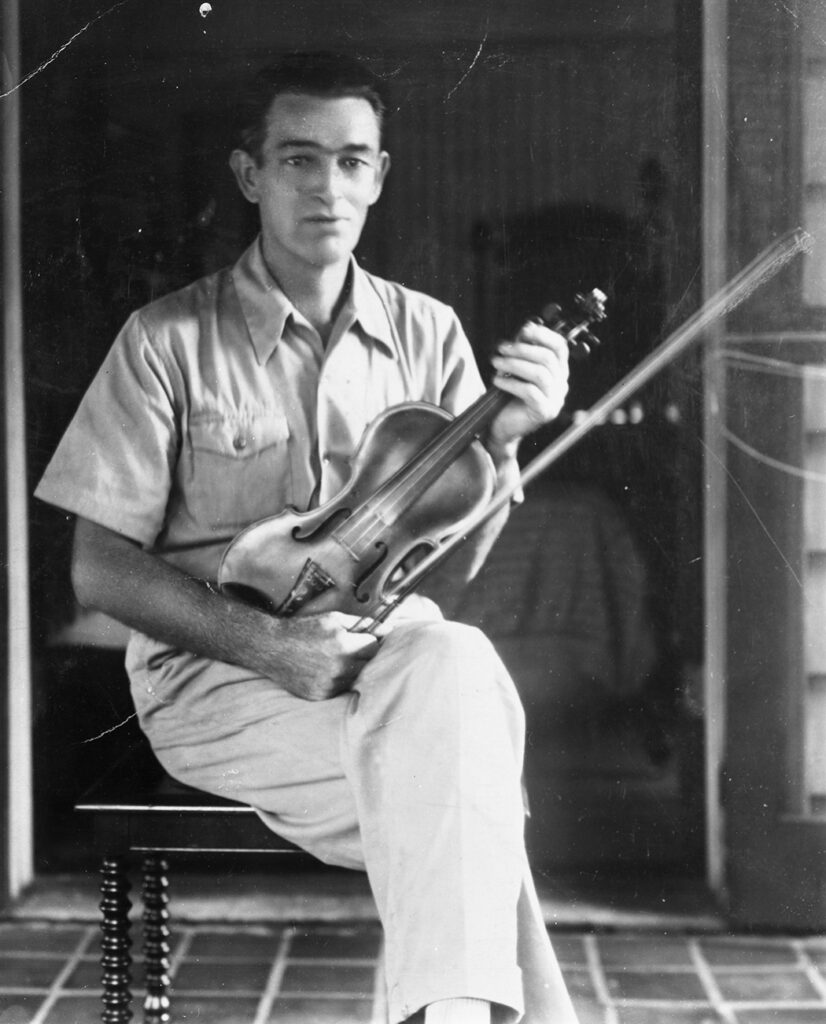

Jimmie Rodgers’ Oscar Schmidt Guitar

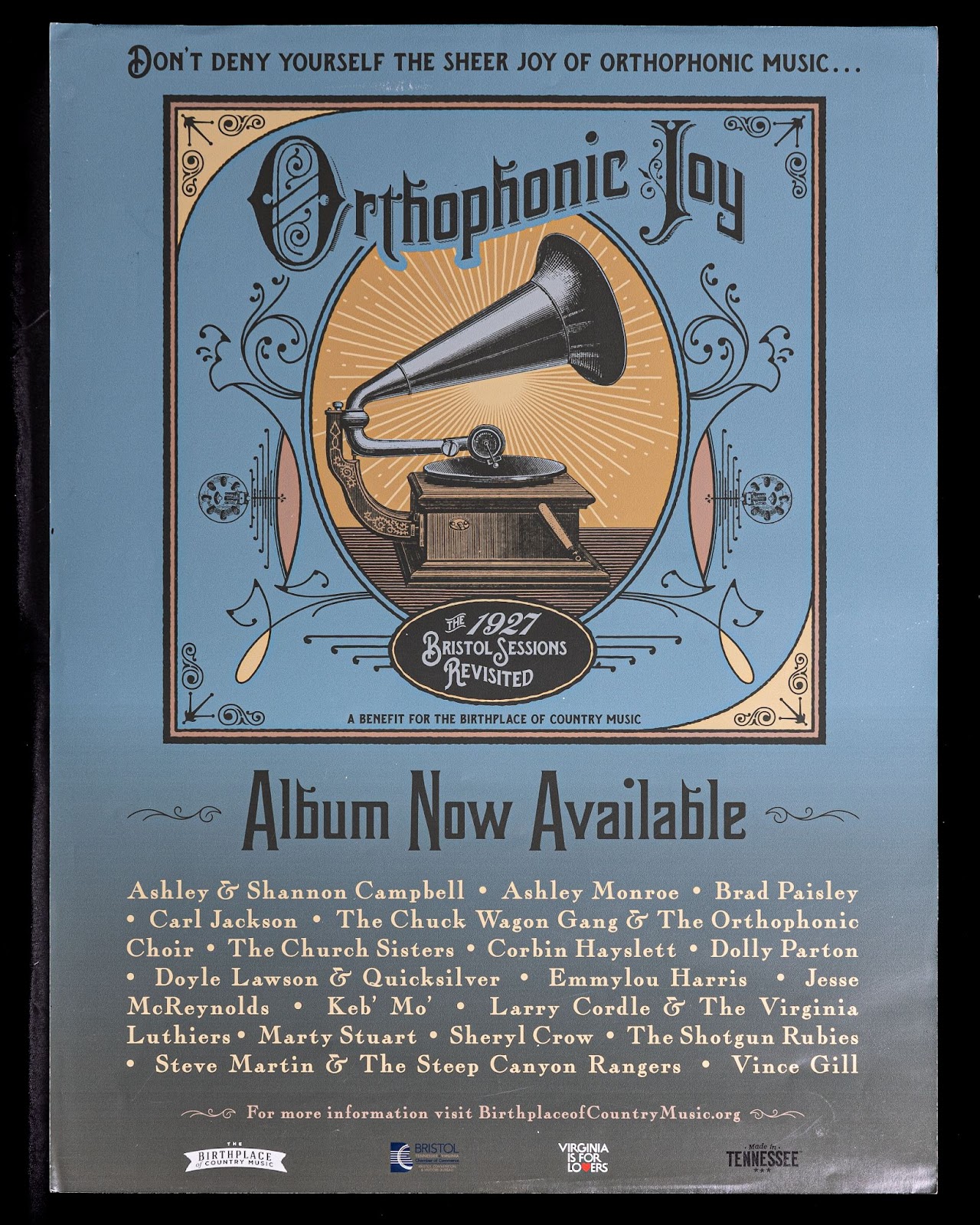

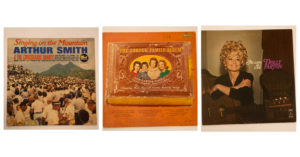

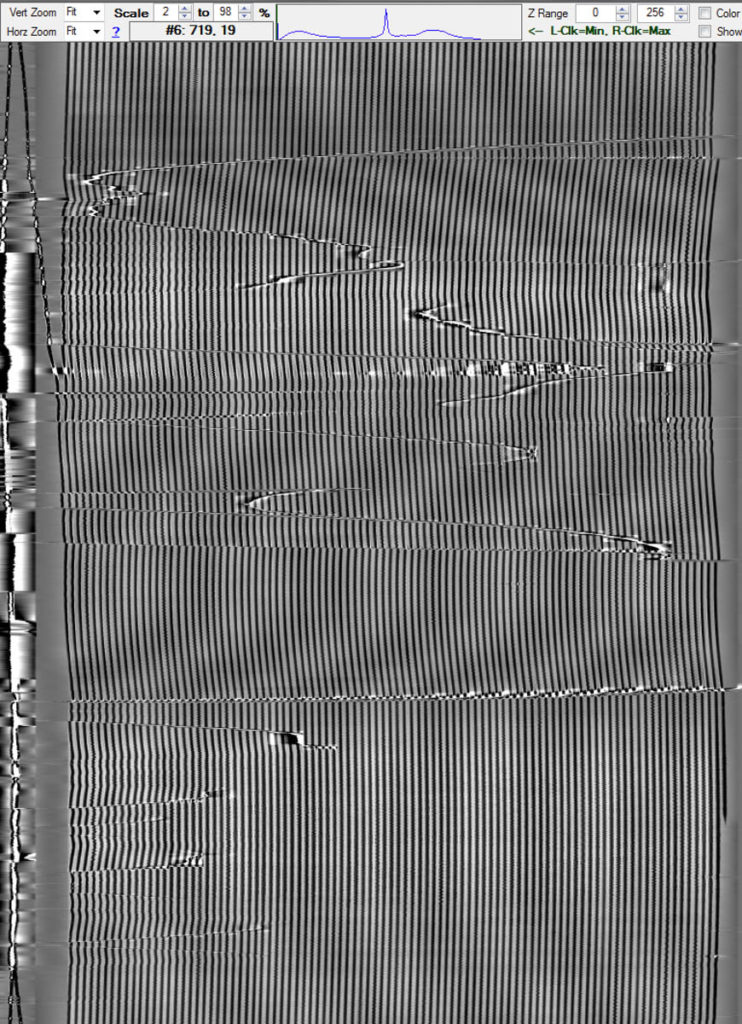

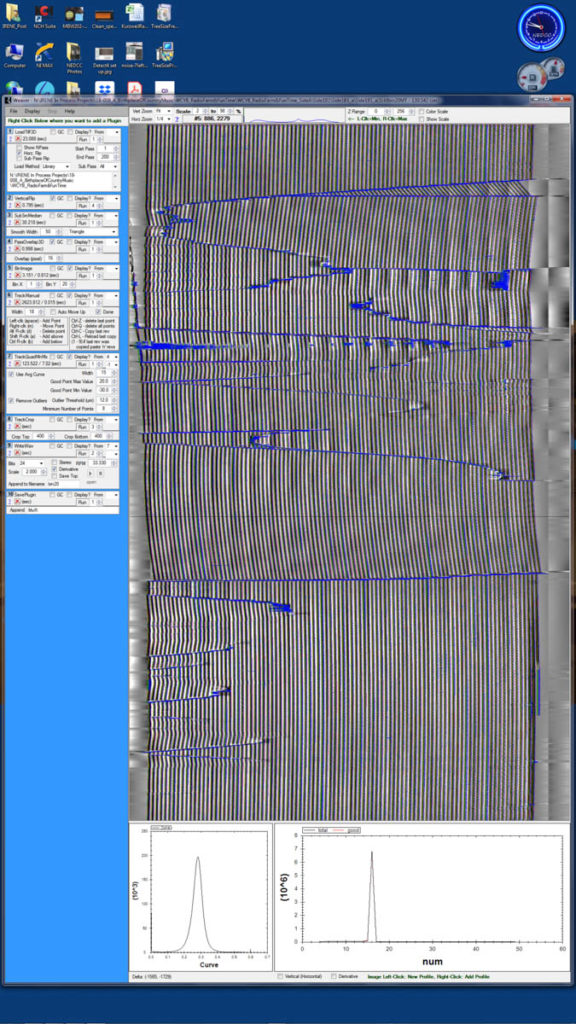

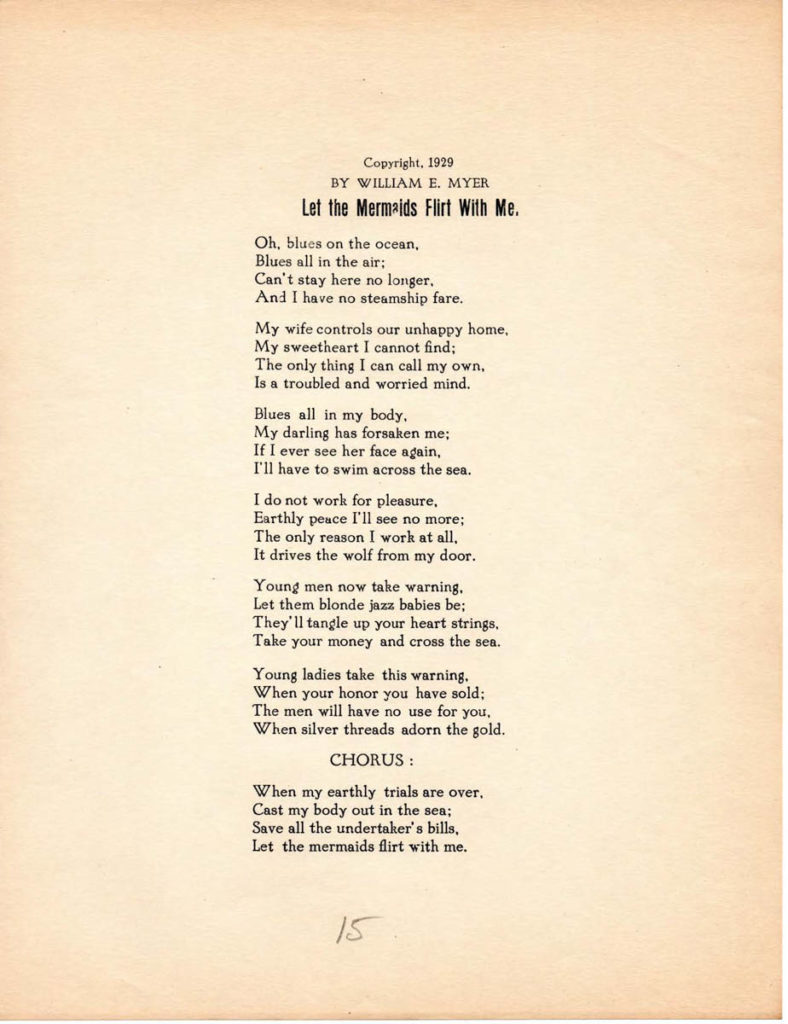

Jimmie Rodgers was the biggest solo star to emerge from the 1927 Bristol sessions. The Birthplace of Country Music Museum is proud to exhibit the three “Jimmie Rodgers” guitars pictured above. The most famous guitar by far is the one on the right, the “Blue Yodel” 1928 Martin 000-45 (read a previous blog post about this guitar here). The guitar on the left, a Martin 2-17 parlor guitar, was not owned by Rodgers but closely resembles the guitar Rodgers played at the Bristol sessions (the actual Bristol Sessions guitar is in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville). The one in the middle, an Oscar Schmidt model with fancy “tree of life” inlay on the fingerboard, is one of Rodgers’ guitars (it has his signature). It is no doubt the guitar with the best stories.

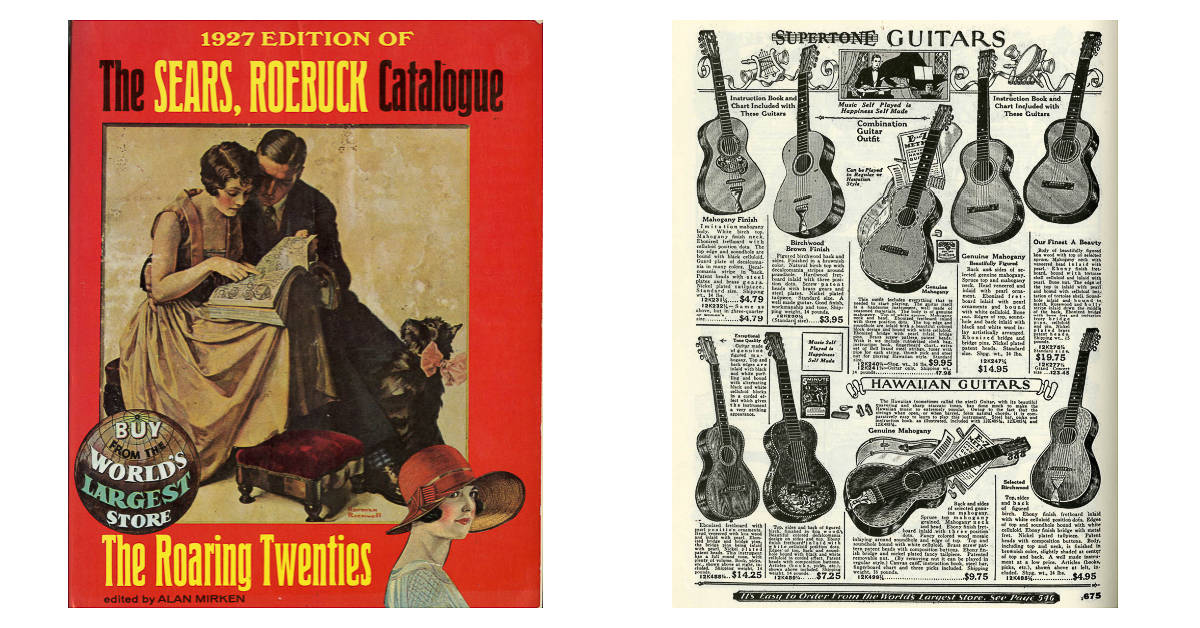

The original Oscar Schmidt company, founded in 1871, sold guitars at prices most people could afford. By the 1920s it was manufacturing 150 different instruments at five different manufacturing plants under its own and a number of other brand names (notably the Stella brand; Maybelle Carter played a Stella at the Bristol sessions). Rodgers’ Oscar Schmidt was a fancy one, likely purchased in 1928 after his career started to take off.

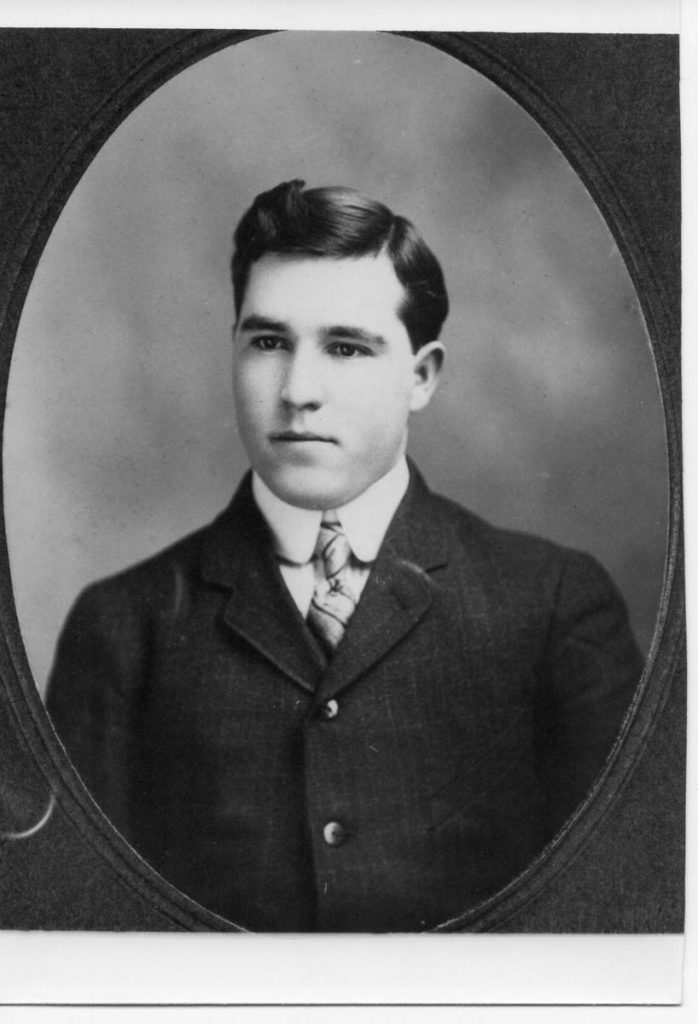

In February 1929 Jimmie Rodgers, headlining a tent show touring the South, played his hometown, Meridian, Mississippi. A 17-year-old Western Union messenger boy named Bill Bruner was in the audience. Bruner was a Jimmie Rodgers fanatic who bought all of Rodgers’ records when they came out. He would spend hours learning the songs note by note and copying Rodgers’ guitar and vocal style, and sometimes played them at a local café.

Rodgers suffered from the tuberculosis that would take his life just four short years later. There were good days and bad days, and this was one of the bad days. He collapsed in his dressing room and the owner of the show would have to tell an unhappy crowd that Rodgers was ill and could not perform.

But here is where things get interesting. It turns out that a tent show clown had heard Bruner play at the café, knew that he was in the audience, and told the show owner that the kid was pretty good. Much to Bruner’s (and his date’s) astonishment, Bruner was escorted backstage and given cab fare to go home and retrieve his guitar.

So after the audience was told about Rodgers being too sick to play, the show owner told them that “we have another Meridian boy who is also a fine entertainer. He sings and plays in Jimmie’s style, and we think he deserves a chance to show what he can do.” The crowd was restive. Then he told the crowd that anybody who wanted to could have their money back if they were dissatisfied after hearing “Bill Bruner, the Yodeling Messenger Boy.” This settled things down a bit.

You can guess the rest. Bruner gave a sensational performance, was called back for six encores, and nobody asked for a refund. The following evening he was invited to Rodgers’ dressing room, where Rodgers gave him $10, decent money in those days. Bruner started to leave but was summoned back, and Rodgers gave Bruner the autographed Oscar Schmidt guitar.

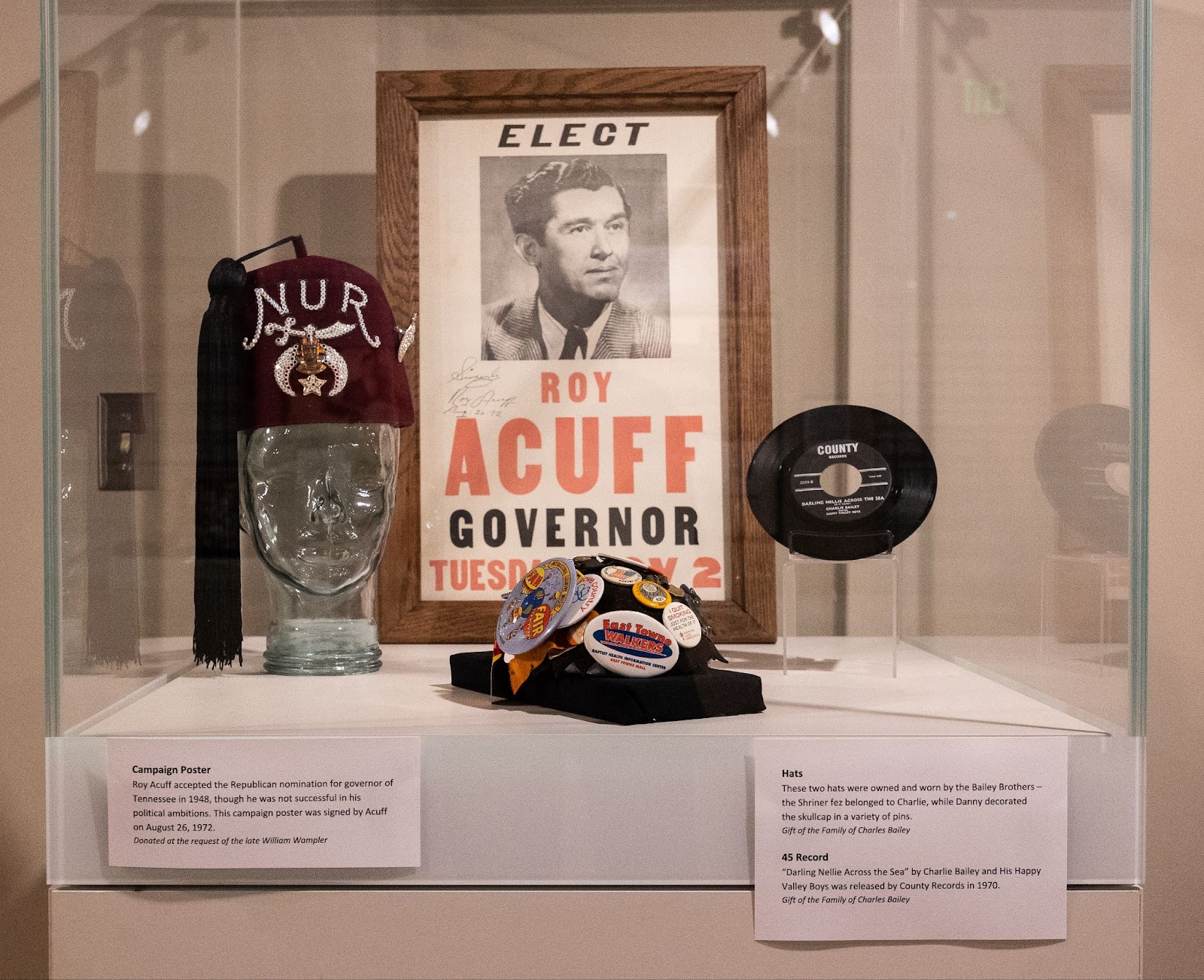

Bruner went on to have a minor vaudeville career and made a couple of records with his prized Jimmie Rodgers guitar. In 1953 Meridian put on a Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Day Gala. The concert featured performances by Country and Western stars Roy Acuff, the Carter Family, Lew Childre, Cowboy Copas, Jimmy Dickens, Jimmie Davis, Tommy Duncan, Lefty Frizzell, Bill Monroe, George Morgan, Moon Mullican, Minnie Pearl, Webb Pierce, Marty Robbins, Jimmie Skinner, Carl Smith, Hank Snow, and Charlie Walker. It was the final performance for the original Carter Family (A.P., Sara, and Maybelle).

Bruner appeared as well, playing the Jimmie Rodgers guitar. Caught up in the excitement of the event, Bruner presented the guitar to another 17-year-old singer, Jimmie Rodgers Snow, the son of country western star Hank Snow, “because I felt like that was what Jimmie would have wanted me to do.”

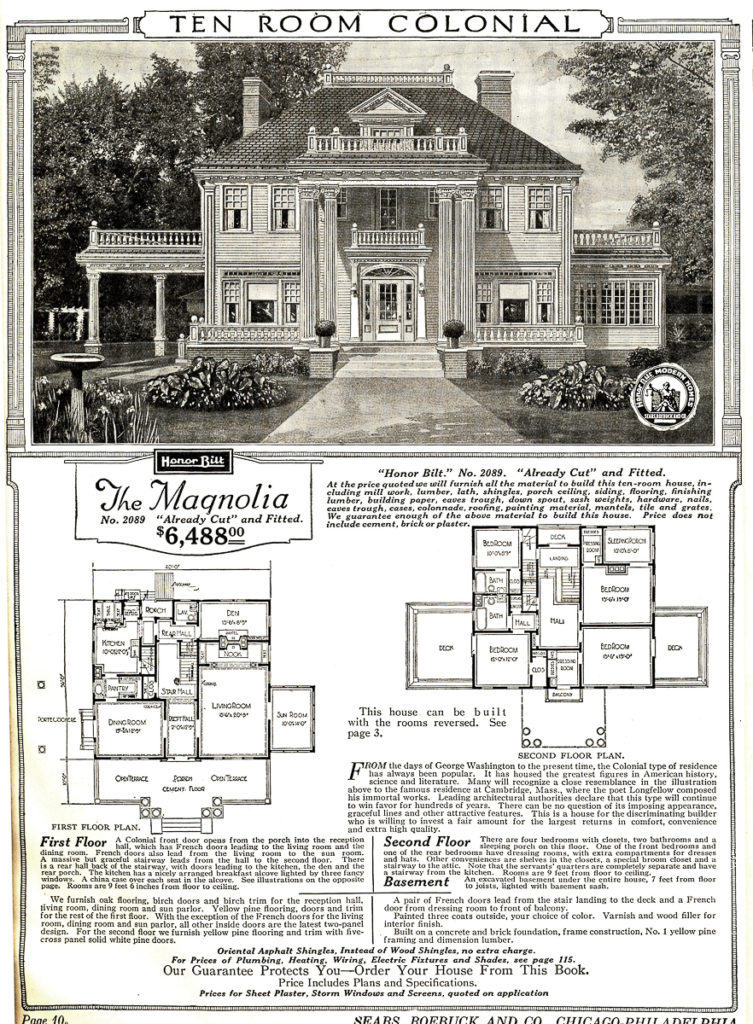

Jimmie Rodgers Snow went on to have a career as a country western star in the 1950s, palling around with folks like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, but gave it up in 1958 to study for the ministry. For many years he preached at the Evangel Temple in Nashville, often referred to as “The Church Of The Country Music Stars” (below is a short YouTube clip of Snow preaching about the connection between rock and roll and juvenile delinquency).

During all of this, the Oscar Schmidt guitar was displayed in the Snow home, nailed to a wall. Years later it was taken down, leaving an outline of the guitar on the painted wall.

The next time you stop by the Museum, take a close look through the sound hole at the back of the Oscar Schmidt. You will see a small shaft of light. The nail hole is still there!

This account was largely taken from Nolan Porterfield’s 1970s interview with Bill Bruner, recounted in Chapter 10 of Porterfield’s book, Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America’s Blue Yodeler.