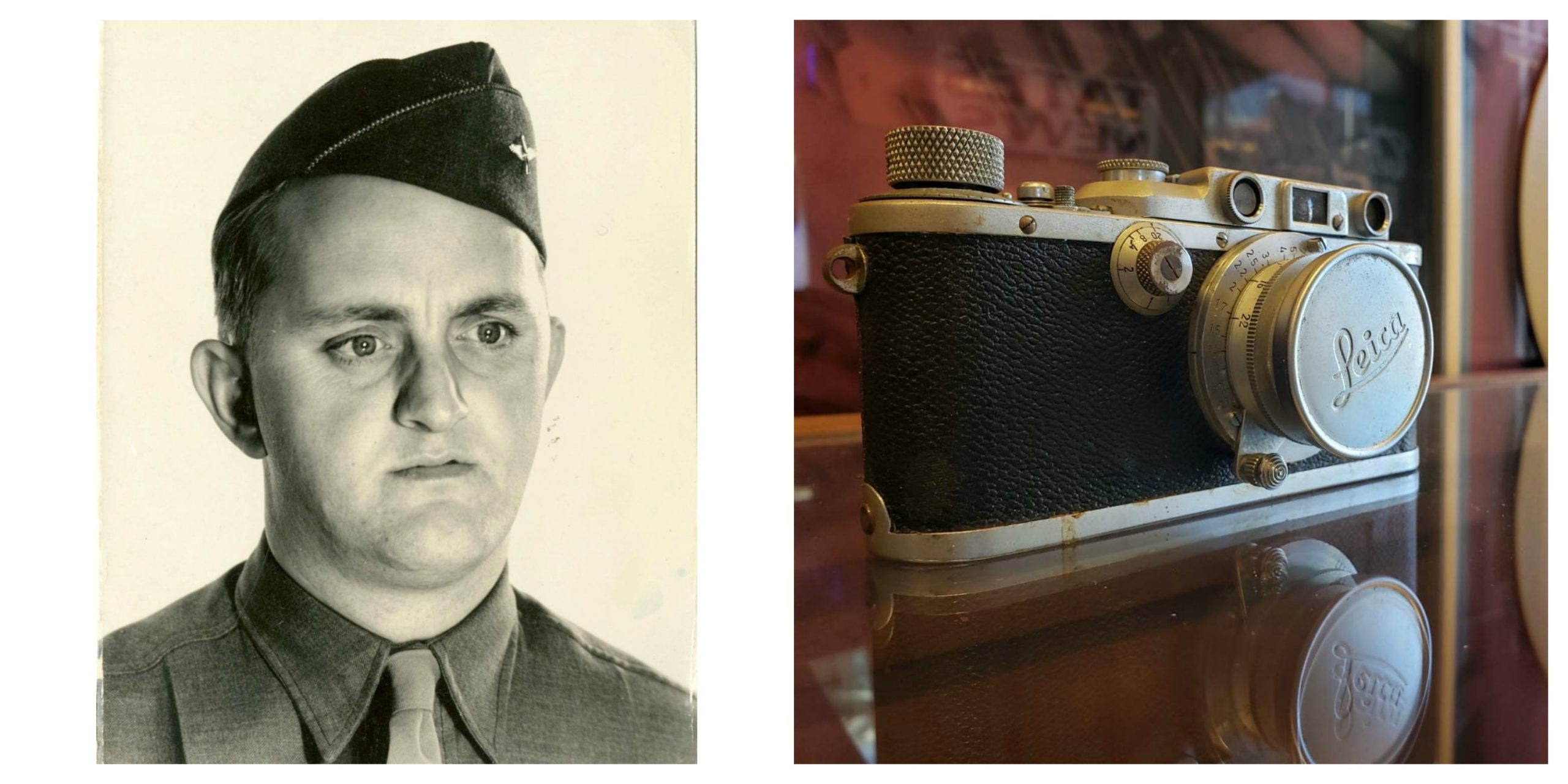

When you think of a specific site associated with country music, the first place that comes to mind is more than likely the Grand Ole Opry. In 2018, Lawrence Inscho, one of our regular contributors to Radio Bristol, donated a personal connection to this iconic venue to the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

But first some background: Lawrence’s father William Lawrence Inscho Sr. served in World War II as a staff sergeant. After Pearl Harbor, he was stationed in Fairbanks, Alaska – with the Alaskan Aleutian Islands as early targets of the enemy, the US military’s position there played a strategic role in the defense of the country. He was eventually stationed in Memphis, Tennessee, and during his service, he went to Nashville for a needed surgery. He met a young woman there and later married her.

The Grand Ole Opry has played host to so many greats of country and bluegrass music over the years, almost too many to count. In the summer of 1945, Inscho Sr. took a series of photographs at the revered Grand Ole Opry stage. The younger Lawrence likes to imagine that these photos were from his parents’ honeymoon.

For us, the photos taken by Inscho Sr. are a true treasure trove, documenting performances from the heyday of the Grand Ole Opry and country music. Some of the most well-known musicians that played at the Opry, like Bill Monroe and Uncle Dave Macon, have their likenesses preserved in these images. Others not quite as famous, like Zeke Clements, are remembered here as well. It’s a real thrill to see these important musicians as we take a gander at some of the photograph collection!

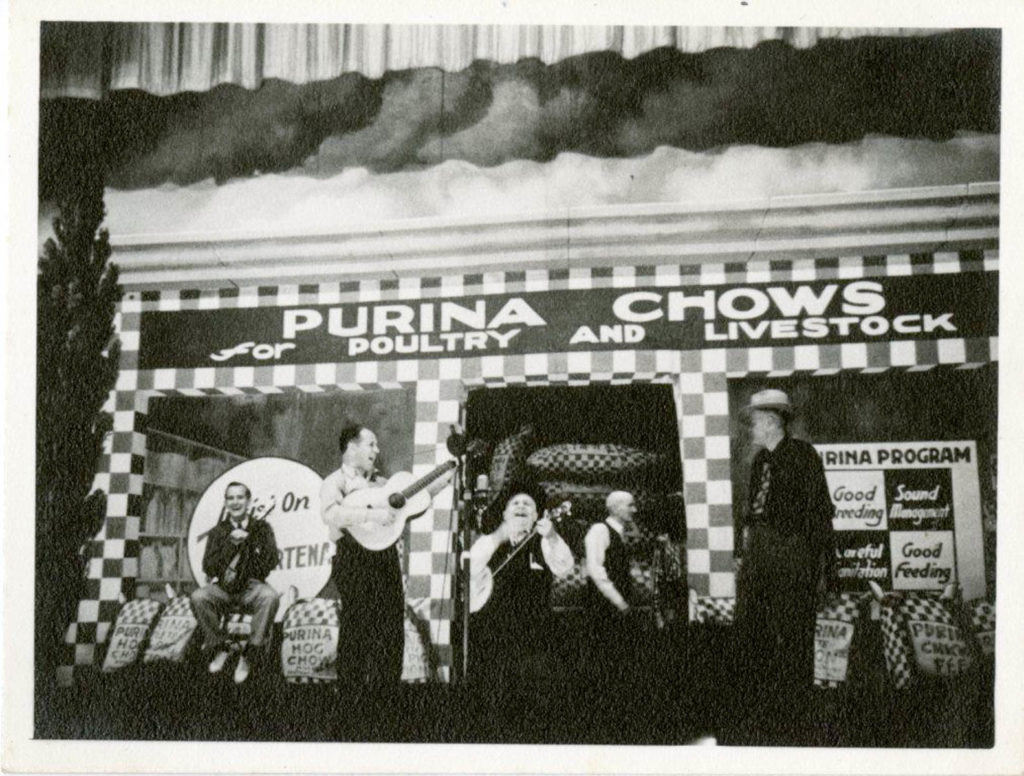

One of the lesser known monuments of country music and the Grand Ole Opry was Pee Wee King, seen here on the far left. Despite his Polish-German musical heritage (he was born Frank Julius Anthony Kuczynski), he co-wrote “The Tennessee Waltz,” which became a standard of the country music genre, and toured and made movies with Gene Autry. King joined the Opry in 1937, and he brought a rebellious side to this traditional venue by defying the Opry’s ban on drums, horns, the accordion, and electrical instruments. In doing so, he was one of the first people to introduce those instruments to country music at the Grand Ole Opry. He also wore the flamboyant, rhinestone-covered suits of Nudie Cohn, introducing this style to many country music artists. These suits became very popular within the genre, and the likes of Elvis Presley also later wore them. Pee Wee King was truly one of the great pioneers of country music.

One of the more unusual musicians featured in these photos was Benjamin Francis “Whitey” Ford, known on stage as The Duke of Paducah. A banjo picker, he founded the Renfro Valley Barn Dance stage and radio show with two other musicians. But he was also a well-known country comedian whose tagline “I’m goin’ back to the wagon, boys, these shoes are killing me!” became a standard. His jokes also influenced the classic country TV show Hee Haw. The Duke later shared the occasional show bill with none other than Elvis Presley.

Zeke Clements, also known as “The Dixie Yodeler,” had some fascinating ventures during his lifetime. One of the bands he was in, Otto Gray and his Oklahoma Cowboys, was the first nationally famous cowboy western band. And one of his most prominent successes was writing the song “Smoke on the Water.” Clements also took acting roles as singing cowboys in multiple B-Western films in the 1930s and 1940s. He even voiced one of the yodeling dwarfs in the 1937 Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. He was quite the character in early country music!

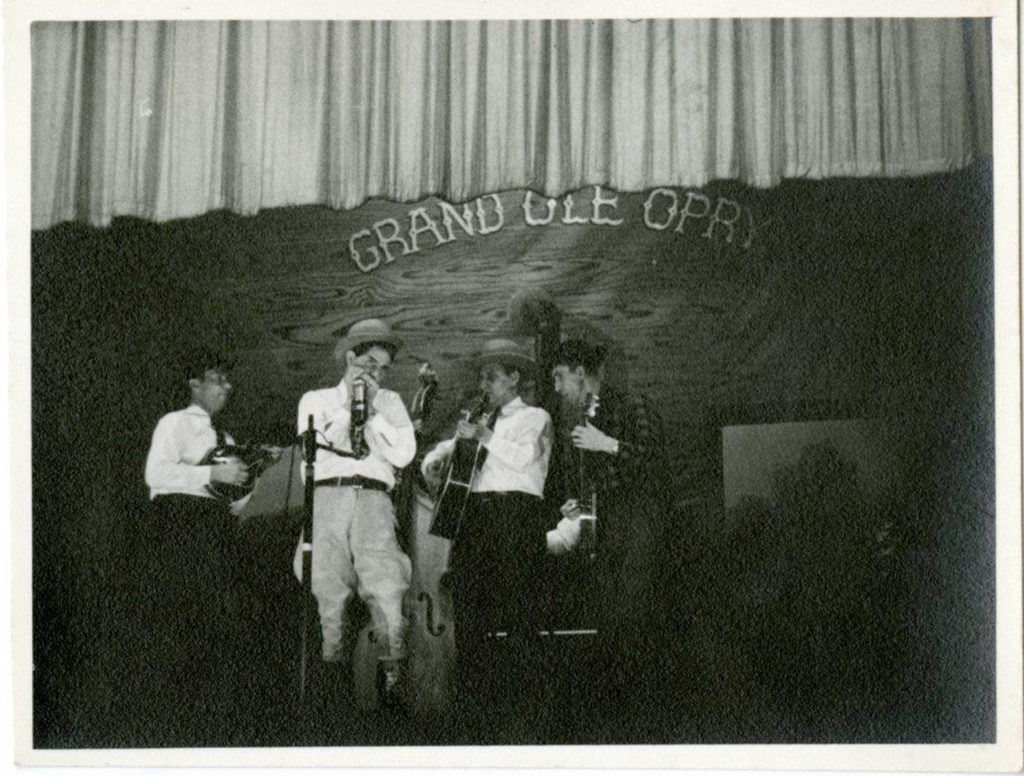

When people think of bluegrass, they think of Bill Monroe, one of the greatest bluegrass musicians that has ever been. This rare early photo of Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys is significant for a few reasons. First, it shows the group before Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs joined. It also shows Monroe playing his Gibson F7, an instrument he played before he turned to his iconic 1923 Lloyd Loar-signed Gibson F5. Further, this is the only known performance photo of the man playing the harmonica, Curly Bradshaw. He only performed shortly with Monroe, and before the discovery of these photos, the only known photo of him with Monroe was a 1944 publicity photo.

At this time, the man on the right, David Akeman, better known as Stringbean, was also a member of the Bluegrass Boys. A banjo player and in the cast of the Hee Haw television series, Akeman was later famously murdered, along with his wife, in his home near Ridgetop, Tennessee, due to a hidden sum of money that was rumored to be in the home. This photo is one of the most fascinating in the Inscho photograph collection.

This last photo shows an old-time element of the show Inscho Sr. saw at the Grand Ole Opry in 1945. It features Dorris Macon playing the guitar and Uncle Dave Macon sitting in the middle with his banjo. A vaudeville performer, Uncle Dave Macon was known for his lively and lengthy performances, which led to him becoming the first star of the Grand Ole Opry.

These photographs by Inscho Sr. reveal a once-in-a-lifetime experience where he and his wife got to see a great show with musicians of huge talent and fabled status perform. This experience was special to Inscho Sr., and the memories and record of them are now special to his son. We feel very privileged that Lawrence chose to share these photographs with us – it is personal stories and objects like these that make up a truly special part of the museum’s collections.

* If you want to hear more from Lawrence Inscho, check out Kris Truelsen’s On the Sunny Side show on Wednesdays. From 10:00 to 11:00 AM every Wednesday, Lawrence shares music primarily from his personal collection, a significant portion of which came from his father.