While December 13 – today – is National Violin Day, here at the Birthplace of Country Music, we celebrate it as National Fiddle Day!

The violin or fiddle is believed to have originated in 16th-century Italy, though there are certainly earlier instruments, particularly from the Middle East, that are viewed as part of the fiddle’s “family tree.” Soon after its appearance or development in Italy, the modern fiddle began to move into other areas of Europe, including England, Ireland, and Scotland, and it was primarily immigrants from these areas, along with French settlers, who brought the fiddle across the Atlantic to North America.

As early as 1736, there are written accounts of fiddle contests in the South, and the fiddle was the primary musical instrument in southern Appalachia through World War II. It was often accompanied by the banjo, making them the foundational instruments for string band music. Despite the instrument’s common association with white rural musicians, a strong African American fiddle tradition developed in the 19th century and Native Americans and Mexican Americans also explored their own fiddle styles in the Southwest.

The four-stringed instrument is played with a bow, though it can also be strummed or plucked. People tend to use the term violin when the instrument is played for classical or chamber music, symphonies, or orchestras, while the term fiddle is associated with Cajun, Irish, bluegrass, folk, oldtime, and country music – tunes where musicians can really let loose and play! Historically, the fiddle was sometimes referred to as “The Devil’s Box” because many people associated the fiddle with dancing, drinking, and merry-making – activities viewed by some as improper.

Left: Blind Alfred Reed’s family brought the fiddle he played on the 1927 Bristol Sessions recordings to the museum’s 90th anniversary in 2017. In this photograph, it is being shown to Ralph Peer II. Right: Charles McReynolds was a part of the Bull Mountain Moonshiners who played at the 1927 Bristol Sessions. McReynolds was a lively fiddle player and a pillow had to be placed under his foot during the band’s 1927 recordings. His grandsons Jim and Jesse McReynolds became big stars on WCYB’s Farm and Fun Time, and Jesse can be seen her playing Charles’s fiddle on Radio Bristol’s revival of the show!

The museum is fortunate to have several fiddles within our collection:

The fiddle on display in the museum’s permanent exhibit was made in 1935. Several artists played the fiddle on recordings from the 1927 Bristol Sessions, including Hattie Stoneman, Blind Alfred Reed, Kahle Brewer, Jesse and Pyrhus Shelor of the Shelor Family/Dad Blackard’s Moonshiners, J. E. Green with Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Baker, Jack Pierce of the Tenneva Ramblers, Charles McReynolds of the Bull Mountain Moonshiners, Norman Edmonds, Wesley “Bane” Boyles of the West Virginia Coon Hunters, and Uncle Eck Dunford. Our display fiddle is very similar to the fiddles that would have been played at the 1927 Bristol Sessions.

This fiddle was owned and played by Herbert Sweet, who played with his brother Earl in the 1920s and 1930s. The inside of the fiddle’s case has handwritten details of several places where they played, including a Gennett Records session in 1928 with Ernest Stoneman and WOPI, a Bristol radio station. Herbert played this instrument well into the 1980s, as told by Ruth Roe, who donated the instrument to us.

A few years back, we received two fiddles from Tennessee Ernie Ford Enterprises. The fiddles belonged to Mr. and Mrs. T. C. Ford, the parents of Tennessee Ernie Ford. They lived in the area throughout their lives, and Ernie referenced his Bristol roots often in his radio and television shows.

This fiddle was owned and played by Charlie Bowman, an East Tennessee museum whose distinctive fiddling style was a major influence on early country music in the 1920s and 1930s. Inside the f-holes on the instrument, there are etchings of “Charlie Bowman” and “1934.” This fiddle is currently on loan to us from Bowman’s great-nephew Bob Cox.

Matchstick modeling has its origins as a pastime of prisoners during the 18th century. Many things can be built out of matchsticks – from architectural structures to tea cups. The museum has two matchstick fiddles in our collection where the bodies of the instruments are made completely out of matchsticks. Made by Wade Nichols and donated to the museum by Anita Morrell from her father Joe’s collection, it would be interesting to know how this unusual construction and wood source affected their sound!

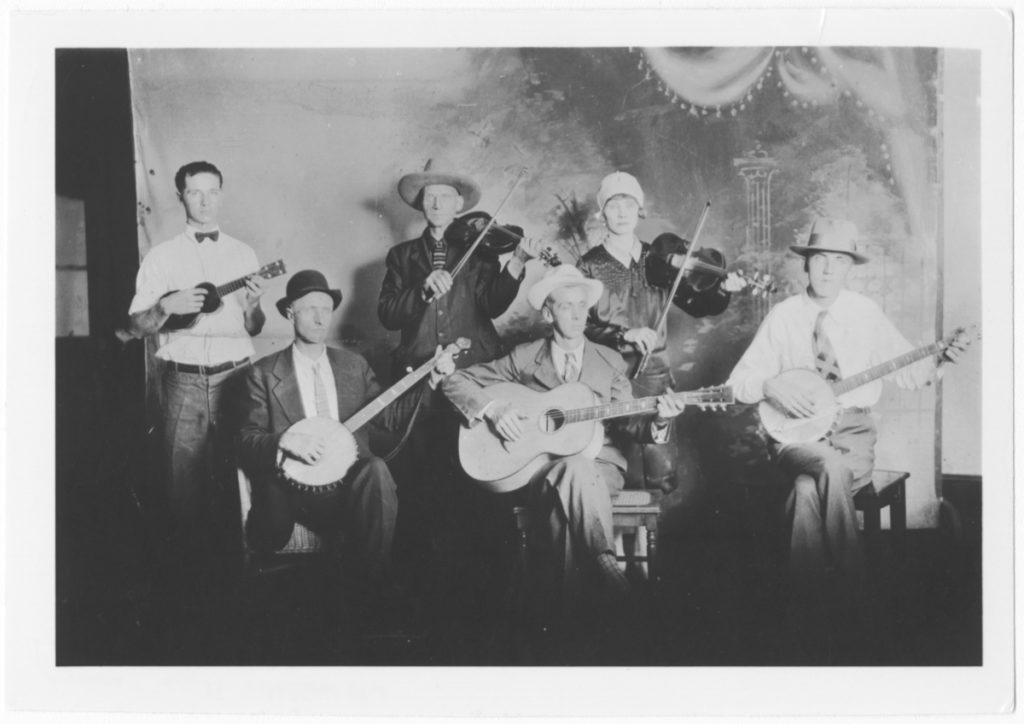

The image at the top of this page is of Ernest Stoneman’s band, known by different names including The Stoneman Family, the Blue Ridge Corn Shuckers, and Ernest V. Stoneman & His Dixie Mountaineers. Two fiddle players are seen on the back row: Uncle Eck Dunford and Hattie Stoneman. From the John Edwards Memorial Foundation Records, #20001, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Julia Underkoffler is the Collections Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.