Music and work have always gone hand-in-hand. Songwriters often use their craft to reflect the realities of day-to-day life – and for most of us, a big piece of our lives is given over to the time we spend doing our jobs. Therefore, it is no surprise to find songs across genres that tell stories of labor.

Our current special exhibit – The Way We Worked, here at the museum from the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service for just a few more days! – inspired the curatorial team to explore the connections between work and music, and in the process gave us a really wonderful playlist of labor-related songs. Check out some of these connections with the songs below and dig a bit deeper into this history with us!

The Way We Worked on display in the museum’s Special Exhibits Gallery. © Birthplace of Country Music Museum

Songs that reflect different forms of labor or jobs are common in early hillbilly music, as well as in contemporary country. The songs are often particular to the time period in which they were written or look back on the past with nostalgia. Several different types of labor are commonly reflected in hillbilly music – especially farming, timber and lumber work, coal mining, and work on the railways – and those themes are also found in later country music.

Farming

At the turn of the 20th century, almost half of all Americans lived on farms. Farm work and a rural lifestyle was a major part of their lives, though farming for subsistence or profit was – and still is – difficult and uncertain. Artists like Ernest Stoneman sang about that uncertainty. For instance, his 1934 recording “All I Got’s Gone” reflected the impact of the Great Depression on rural people who had bought more than they could afford before it hit, only to lose everything once the stock market crashed so that they had to go back to subsistence farming or survive without much else to support them.

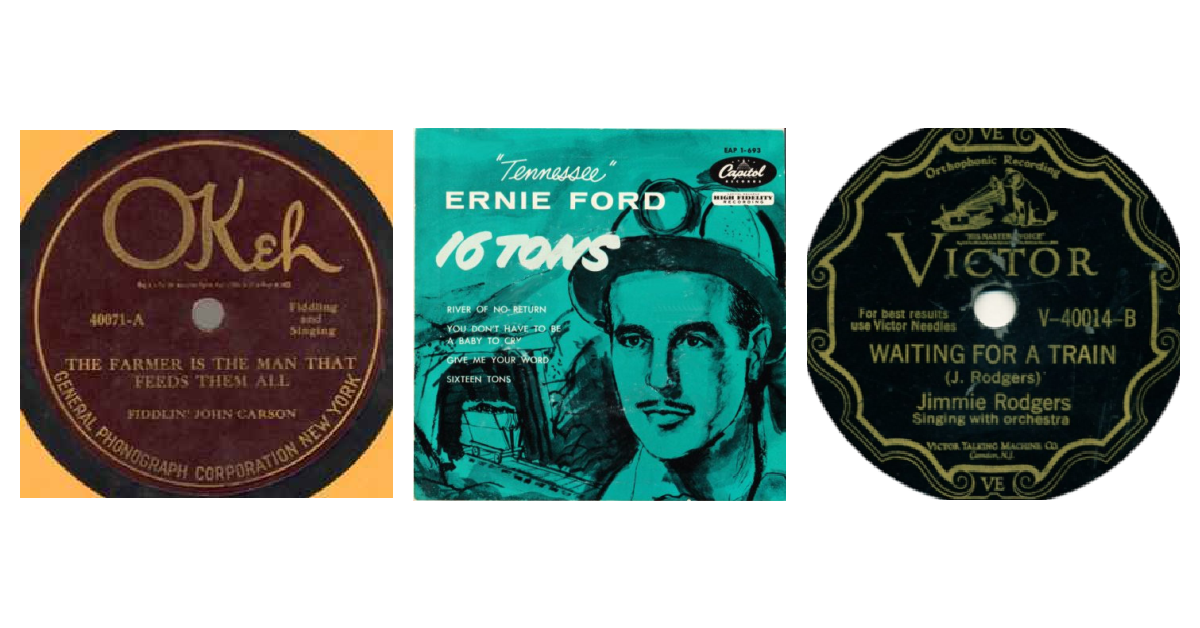

Other songs of the era focused on both the importance and the precariousness of the farming life, songs like Fiddlin’ John Carson’s “The Farmer is the Man (That Feeds Them All)” (1924) and “The Honest Farmer” (1925). Carson’s 1924 recording was later taken up and sung by Pete Seeger as a protest song. One of The Carter Family’s songs – “The Homestead on the Farm” (1929) – is told from the perspective on a man who has left his family farm behind to make his way in the world and remembers it fondly with lyrics like “You could hear the cattle lowing in the lane / You could almost see the fields of bluegrass green.” Many modern country songs hearken back to the farming days with nostalgia and also celebrate the work that farmers do – for example, “International Harvester” by Craig Morgan (2006) and even “She Thinks My Tractor’s Sexy” by Kenny Chesney (1999)!

Timber

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, abundant and rich natural resources, coupled with low land costs, made Appalachia the site of a major boom in the logging industry. This brought huge changes in land ownership and usage – with land being taken over by outside investors and corporations – and often had devastating environmental and social effects on the region. And it wasn’t just the Appalachians that saw the growth of timber work; other areas of the country (and beyond) have a similar history, and as with farming, songs were sung about this common labor. For instance, the lyrics to “Once More a-Lumbering Go” was written down by a New England lumberman named John Springer in the 1850s, and several versions of the song were later recorded in the field by song collectors and ethnomusicologists. Smithsonian Folkways produced an album in 1961 called Lumbering Songs from the Ontario Shanties, and the library at the University of Wisconsin-Madison created a K-12 lesson plan about Wisconsin’s lumberjack songs. Later artists have also recorded songs about the timber industry, including Johnny Cash’s “The Timber Man” from his 1975 children’s album and Bill Stains with “The Logging Song” (1979).

Coal Mining

Coal mining has been a major part of Appalachian communities for over a century and holds a special place in the economic and environmental history of this region. Therefore, it is only natural that working in coalfields and living in coal towns has provided a source of musical inspiration for many, including songs about the hazards and dangers of this labor and the conflicts between workers and the coal companies that employed them. Blind Alfred Reed’s “Explosion in the Fairmount Mines” (1928) and Hazel Dickens’ “Black Lung” both highlight the very real dangers miners faced, both deep in the mines and after they’ve left them behind.

One of our favorite songs about coal mining is “Sixteen Tons,” written by Merle Travis and recorded by Bristol’s very own Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1955, along with a host of other artists over the years. Travis’s lyrics reflected the bravado of the men who toiled underground in dangerous conditions and then later sometimes came to blows in their down time, but most importantly it also focused on the struggles that miners and their families faced living in a company town and owing their bosses their wages to survive. With lines like “You load sixteen tons, what do you get / Another day older and deeper in debt” and “I owe my soul to the company store,” those economic hardships certainly become clear to the listener. Songs like Florence Reece’s “Which Side Are You On?” Joe Hill’s,” Hazel Dickens’ “They’ll Never Keep Us Down,” and numerous songs about union activist Joe Hill underline the struggle workers’ too often faced for safe working conditions and livable wages.

Railroads

Railroads were also a major industry – and hugely important to the transportation of resources like timber and coal – in the United States in the mid- to late-19th century and early 20th century, and large numbers of Americans worked for the railroad. Train songs were particularly popular in the early 20th century and covered a wide variety of subjects, including railroad construction and changing technology (for example, various songs about John Henry, the “steel-driving man”), rail travel, train bandits, the wandering hobo living life on the rails (Jimmy Rodgers’ “Waiting for a Train,” 1929), and even as a spiritual metaphor within sacred and gospel music (The Carter Family’s “The Little Black Train,” 1937). And sometimes songs turn the usual story on its head – for example, Amythyst Kiah recently recorded “Polly Ann’s Hammer,” a song based on the John Henry tale, though this time told from the perspective of Henry’s wife.

However, railway songs very often focused on train wrecks – an all-too-frequent danger of the early railroading years. Some lamented passengers who lost their lives, but most of them memorialized the crewmen killed in the line of duty on the rails, along with celebrating their heroism. Songs like Henry Whitter’s “Wreck of the Old 97” (1923), Blind Alfred Reed’s “The Wreck of the Virginian” and Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Baker’s “The Newmarket Wreck,” both recorded at the 1927 Bristol Sessions, and “Engine 143” by the Carter Family (1929) share the news of these tragedies in chorus and verse form. Later artists hearken back to these days in song too – for example, “The Great Nashville Railroad Disaster (A True Story),” recorded by David Allan Coe in 1980.

A train wreck near Benhams, Virginia, in the 1920s. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Bristol Historical Association

Work and Music

This post just touches on the tip of the iceberg for songs about work – there are so many out there, and so many themes and topics explored in those songs that there’s not room in one post to cover them all! For instance, just a few include Hattie Burleson’s “Sadie’s Servant Room Blues” (1928), which notes the indignities of work when you are required to work long hours for low pay, while being treated with little respect due to race; Dollie Parton’s “9 to 5” (1980), a beloved movie theme song that was inspired by a women’s activist movement that fought for equal pay and treatment in the workplace; Johnny Paycheck’s “Take This Job and Shove It” (1977), chronicling the frustration of a man who worked for years for little reward – and then, being a country song, he also lost his girlfriend or wife; and Sam Cooke’s “Chain Gang” (1960), a song that reflects the harsh realities of Southern justice through unpaid labor in the Jim Crow era.

You can check out the Virtual Speaker Series presentation we did on this topic in December here, along with three related playlists: here, here, and here! I hope this post and the music it celebrates give you a starting point for exploring the history of work through song!

The Way We Worked special exhibit is on display at the museum through Sunday, January 23 so come see it while it is still here! And tune into our Radio Bristol Book Club show on Thursday, January 27 at 12:00pm as we continue our exploration of work history through a discussion of Denise Giardina’s Storming Heaven, followed by an interview with the author.

René Rodgers is Head Curator at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum. Erika Barker is the museum’s Curatorial Manager.