This month is African American Music Appreciation Month, to celebrate, I want to shed some light on a particularly underappreciated artist. As time passes, some artists are forgotten for their achievements until someone rediscovers them. One of these artists is Linda Martell, the first commercially successful Black female artist. A self-titled website calls her the “unsung hero of the genre,” and a Rolling Stone article refers to her as “Country’s Lost Pioneer.” Recently, Martell has reentered the public radar after being mentioned in Beyonce’s album Cowboy Carter, specifically on two songs, “Spaghetti” and “The Linda Martell Show”. After the release of the album, magazines such as The Rolling Stone soon began publishing articles with titles of “Beyoncé’s ‘Cowboy Carter’ Includes a Shout-Out to Linda Martell — Who Is She?” Let’s find out!

Linda Martell was born Thelma Bynem on June 4, 1941, in Leesville, South Carolina. She was one of five children to parents Willie Mae and Clarence Bynem. Her mother worked in chicken slaughterhouses, while her father was a sharecropper and preacher in a Baptist Church. Her church life influenced her love of music, and her gospel roots can be heard on later recordings. She recalled that growing up, her family would listen to the radio station WLAC which was based in Nashville and played country music. Her father’s favorite song was “Your Cheatin’ Heart” by Hank Williams, and he would sing it around the house often.

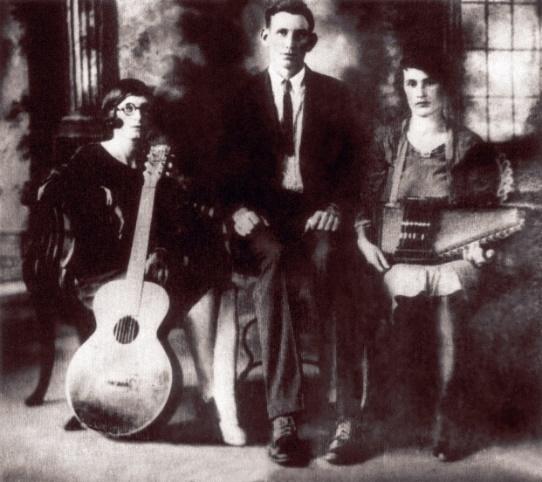

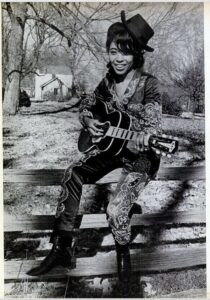

In her teenage years, she formed an R&B trio with her sister and their cousin, creating “Linda Martell and the Anglos” (later spelled “Angelos”). By the early 1960s, she was touring with the group and performing at clubs. They caught the attention of a local DJ named Charles “Big Saul” Greene, who suggested Bynem use the name Linda Martell. He wrote her a note stating, “Your name is Linda Martell. You look like Linda. That fits you.” The group soon disbanded, but only after recording a few singles with reputable labels.

Bynem, now going by Linda Martell, continued as a solo act performing in nightclubs. While singing on a Charleston Air Force base in 1969, the crowd begged her to perform a few country songs and heard by William “Duke” Rayner. He offered to buy a tape of her performing. Originally, Martell thought Rayner was a “kook” and ignored him, but eventually decided to hear him out. He then introduced her to Shelby Singleton Jr., who was involved in the Nashville music industry.

During her first meeting with Singleton, he shocked her by asking her to sing country. She recounted later that she had performed mostly pop up to that point. At this point, Black country musicians, especially female ones, still had a lot of trouble getting signed onto labels and performing. Singleton signed on both black and white performers but considered Martell a risky move because she was a woman. All Black country artists who were successful up to this point were men. Nevertheless, Martell signed a management deal on May 15, 1969, and a record deal.

The next day she recorded a cover of “Color Him Father” by the Winstons. It was originally in the funk and soul style, but Martell transformed it into a mix of country and R&B. But more importantly, she focused on the storytelling aspect of the song. At the height of the Vietnam War, this song resonated with people. It is a story from a boy’s perspective after his father died during the war. His widowed mother remarried, and the song tells the boy’s view of this new father figure in his life – a very harsh reality for many in the years surrounding the song’s release.

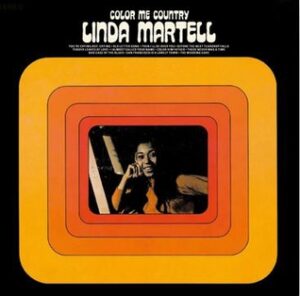

They finished the album in a single 12-hour recording session. The album, called Color Me Country, included eleven songs, but “Color Him Father” was released on the record and as a single. It reached #22 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, the highest a Black female country artist had reached until the release of Cowboy Carter by Beyonce earlier this year. Martell soon appeared on TV, in live shows, and even at the Grand Ole Opry. She was the first solo Black female country singer to appear on the Opry stage and received two standing ovations.

She was also invited to perform on Hee Haw, a comedy and country music show. Despite her success, racism plagued her career. After hearing her during rehearsals, a show executive approached her and attempted to correct her pronunciation of her own lyrics. She did not listen and sang the words the way she always did. She later stated, “He wasn’t too happy about it. But I did anyway.” Charley Pride, a well-known Black country artist who had been performing for almost two decades at that point, gave Martell advice during a party: “Develop a thick skin and get used to the name-calling.” She tried to ignore it but never truly got used to it and refused to learn to tolerate how she was being treated.

In the South, she was advertised as the “First Female Negro Country Artist.” Her first gig after signing with Singleton was in Poplar Bluff, Missouri. She later recounted that night, “You’d be singing, and they’d shout out names, and you know the names they would call you.” There was another instance when a promoter in Beaumont, Texas, canceled her show after discovering that she was black. He claimed that her “Fans would tell her she didn’t sound black.”

Singleton recorded her record with a separate label from his regular SSI International label. This sister label was called “Plantation Records”. When she confronted Singleton about the racism behind that name, he denied it and said he chose it with no particular meaning. She stated in later interviews that she told him, “What you are telling me is that black people belonged on the plantation!” She recorded only one album with Singleton and Plantation Records.

In May 1970, Rayner sued Martell because he believed that he deserved a higher commission from her. Singleton managed to make the issue go away, but Martell had other concerns. Singleton was focusing his attention more on another artist named Jeannie C. Riley. This was not simply a suspicion but something Singleton himself told Martell he was doing intentionally. After her year-long contract expired, Martell left Plantation Records. However, when she attempted to record with a new label, Singleton threatened to sue them, causing her deal with them to collapse. This trend continued and she was effectively blackballed, her reputation ruined, and she was forced into an early retirement in 1970.

Despite her incredible achievements, her short career caused her to be largely forgotten in country music history. After her country music career ended, Martell spent the next two decades living a nomadic lifestyle, singing in bars and clubs, and on a cruise in California. At one point, she ran a record store in Bronx, New York, and at another, she was in Florida, where she joined an R&B cover band with her brother. Eventually, she returned to South Carolina to be with her family.

After her father’s death in 1991, she became a school bus driver and later worked in a classroom helping children with learning disabilities. She became a local hero to some, but others still had no idea who she was. When magazines reached out for interviews, many remembered her as a “kindly older lady who worked for the school system.” After being diagnosed with cancer in 2004, she retired from her job. Up until 2011, she performed with a band called Eazzy, which covered R&B songs. For years, she lived alone in a mobile home until her health decreased. After that, she moved in with her daughter Tikethia Thompson.

From time to time, she has come up in the media. She was mentioned in the 2013 film A Country Christmas Story starring Dolly Parton. It follows the story of a biracial girl who aspires to be a country singer. Parton tells her the story of black musicians in the genre, including Martell, showing her the LP cover of her only record, Color Me Country. A more recently successful black country artist, Rissi Palmer, named her podcast started in 2020 after Martell’s album and plays her music on the show. In 2021, Martell was nominated for and won the CMT Music Awards Equal Play Award. That same year, her filmmaker granddaughter Marquia Thompson started a GoFundMe in honor of creating a documentary about her grandmother’s story titled “Bad Case of the Country Blues.” And, of course, most recently, she was mentioned in two tracks off of Beyonce’s album Cowboy Carter.

Guest Blogger Donna Walker is a student at King University and a Birthplace of Country Music Museum Intern.