By Sam Parker, Curatorial Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

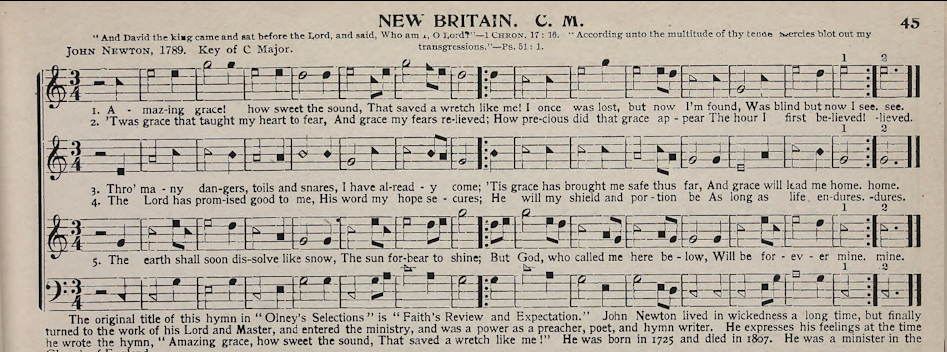

Around the time of the 1927 Bristol Sessions, it wouldn’t have been too out of the ordinary to find oddly-shaped musical notes in your church’s hymnal. In the United States, a lack of formal musical education led to the use of shape-note systems, which combined with Puritan religious traditions in the early frontier to create a unique form of vocal worship music, most commonly referred to as sacred harp singing. Some of the musicians who recorded at the sessions, like The Tennessee Mountaineers, were church groups who might have used shape-notes or began their interest in music with shape-note singing in church.

![The cover of the original "Sacred Harp" hymn book. It is old and worn, reading "The Sacred Harp, a Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes, Odes, and Anthems; selected from the most eminent authors, together with nearly one hundred pieces never before published. Suited to most metres, and well adapted to Churches of every denomination, singing schools, and Private [word obscured]. With Plain Rules for Learners. By B.F. White and E.J. King](https://birthplaceofcountrymusic.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/image11-300x199.jpg)

In these schools older rules of musical composition were ignored, allowing newer styles to flourish, but as those in the cities pushed back in an effort to cling to more traditional European-styled music, these newer styles moved south and west, finding fertile ground in the Appalachian region around the beginning of the 19th century.

At this time, a vital component of sacred harp music was adopted: the shape note. Assigning specific shapes to different notes assisted in sight reading for those new to music, and allowed music to flourish on the frontier where formal musical education was rare. Many books used these shape notes, but none would be so influential as the eponymous The Sacred Harp.

Printed in 1844, The Sacred Harp was originally published in Philadelphia, but it eventually found its way to Northern Georgia, where it spread along the Appalachian mountains along Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. George Pullen Jackson, a Musicologist specializing in Southern Hymns, surmised that at one point, besides the Holy Bible, The Sacred Harp was the most widely-owned book in the rural South.

The Harp itself was put together by two Georgia Baptists, Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha J. King, the latter of whom composed more songs inside the book than any other, and died the year it was published. White also founded the Southern Musical Convention, which served to promote the sacred harp style of music. During the two decades he led the Southern Musical Convention, White expanded The Sacred Harp greatly, almost doubling the number of songs within.

Much of the music found in The Sacred Harp retains Calvinistic themes from its Puritan origins, stressing the natural sin of man while glorifying the sovereignty of God. Many hymns also focus on the afterlife, shunning this world and longing for death, as in the piece “I’m Going Home” —“I’m glad that I am born to die, From grief and woe my soul shall fly, and I don’t care to stay here long.”

One of the more unique aspects of sacred harp singing is the organization of the singers. Performances are very informal, emphasizing fellowship and singing as a group over individuals, with the singers arranged in a square facing each other, grouped by what part they sing: tenor, treble, alto, and bass. Instead of a conductor, a volunteer leads the group for one or two songs before another stands to replace them in keeping time. Anyone is welcome to lead the group, regardless of gender or age. Sacred harp singing typically takes up most of the day, so all who want to lead get a chance.

Typically, a song starts with just vocalization, each part singing the syllable instead of the word for each note. You might already know the do-re-mi solfège from The Sound of Music, but sacred harp uses only fa-sol-la-mi, each assigned to the four shapes used in its shaped note music. There is also the complete absence of instruments, the songs are usually sung a cappella, as it’s believed the term “sacred harp” refers to voices raised together in song. The singing is emotional, and it’s loud—sacred harp singers prefer the acoustics of a small, wooden church compared to the large concert hall, and it creates a sound unlike any other.

As mentioned before, a usual sacred harp performance is an all-day affair. Singing begins in the morning, and then there is a break at lunch, where the congregation exits the church for the Dinner on the Grounds. An outdoor meal spread over many tables awaits them outside, after which they return indoors to continue singing until the afternoon. It isn’t uncommon for the closing piece to be “Parting Hand,” a slow piece bidding farewell to each other. One video of a performance of the Irish Sacred Harp Convention shows the group standing and embracing one another as they sing: “Oh could I stay with friends so kind, how would it cheer my drooping mind! But duty makes me understand, that we must take the parting hand.”

Sacred harp survives both in church services in the South, as well as conventions where singers travel long distances to take part in many performances over multiple days. Altogether, sacred harp evokes the ideas of pan-denominational worship and American innovation of traditional European ideas, as well as being a persevering hallmark of the combination of religious influence and material hardship in American music. Though it has come a long way from its Dissenter origins, you can still find hints of its Puritan roots in its lyrics and messages—when listening to the song “Babylon is Fallen” talk of the destruction of the enemies of God, and how Christ will return to rule with a rod of iron, it isn’t difficult to imagine the Puritans huddled in the lower hold of a ship in a storm, singing together as they make their way to the New World.