“Do you remember when…?”

“Let me tell you about your grandmother’s apple butter…”

“Uncle Roger, I want to hear the story about the time you thought you’d swallowed a water dog!”

November is Family Stories Month, and even though we are still in the middle of a pandemic right now, that doesn’t mean that we can’t share family stories with each other – whether it be in smaller, more socially distanced gatherings; through Zoom or WhatsApp or FaceTime; by writing them down in journals and scrapbooks; or whatever method takes our fancy!

Recording and telling stories – especially family stories – is a big part of southern and Appalachian culture and tradition. From fictional folk tales to the recording of your clan’s names in the family Bible, from the poetry and the storytelling of the region’s music to the family anecdotes we share around the table – all of these are ways for us to pass on our history, big and small, and to remember the good and the hard times.

My family is full of story tellers (my Uncle Roger DID think he swallowed a water dog once, and it is my favorite story to hear, over and over again – for those who don’t know, water dog is another name for a hellbender salamander). On my mother’s side of the family, meals and gatherings are filled with tall tales, stories, remembrances, exaggerations, all told in a southern fashion – in other words, slow and often rambling into other tangential realms. On my father’s side of the family, a cousin’s interest in genealogy has led to family trees and records way beyond the stories we’ve told to each other about more recent ancestors and descendants.

A hellbender is a type of giant aquatic salamander – also known as water dog, snot otter, and mud devil, amongst others. How my uncle was convinced that he had swallowed a water dog – in all probability an impossibility – involved my mother and her sister and their desire to make their younger brother sweat. Image from Wikimedia Commons, photographer: Brian Gratwicke

Family stories – and other historical and personal recollections – told through oral histories is one way that museums and other cultural institutions “collect” data and content for exhibits, research, archives, and programs – and for future generations. Here at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum we have incorporated oral histories and family stories into our exhibits and programming in multiple ways:

- Upstairs in our permanent exhibits, a display titled “I Was There” shares excerpts from interviews with Ralph Peer, Ernest Stoneman, Maybelle Carter, Georgia Warren, and Clarice Shelor, giving first-person accounts of the 1927 Bristol Sessions.

- In 2015 we held a “Tennessee Ernie Ford History Harvest,” an event where we invited members of the public to come to the museum to share any photographs or paper items, objects, and stories related to Ford, his life in Bristol, and his career. We scanned the images, newspaper articles, and other documents; photographed the objects; and spent several hours recording stories and memories of Ford, still a Bristol hero to so many. Not only did this give the public a chance to explore local history more deeply, but the resulting materials are now part of the museum’s archive and can be used for future educational and programming purposes. We hope to hold other “history harvests” in the future – for instance a hoped-for partnership with Black in Appalachia to record stories of African American musicians in this region.

- At the museum’s symposium on the 90th Anniversary of the 1927 Bristol Sessions in 2017, we recorded oral histories by many of the descendants of the 1927 Bristol Sessions artists to learn more about the musicians who played and recorded here, to give context to the wider history, and to explore the impact that moment had on them, their families, and beyond. We have also interviewed different family members for blog posts, such as our post on Hattie Stoneman.

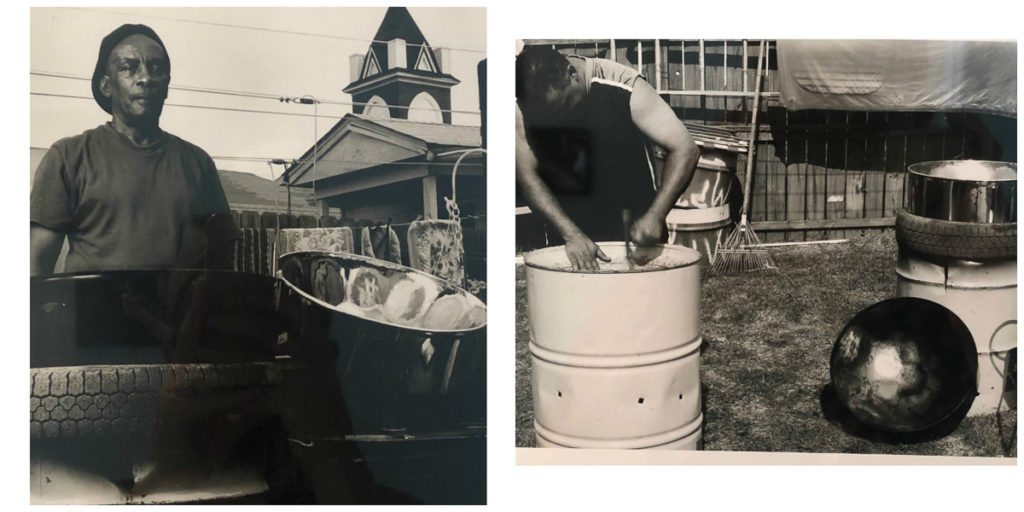

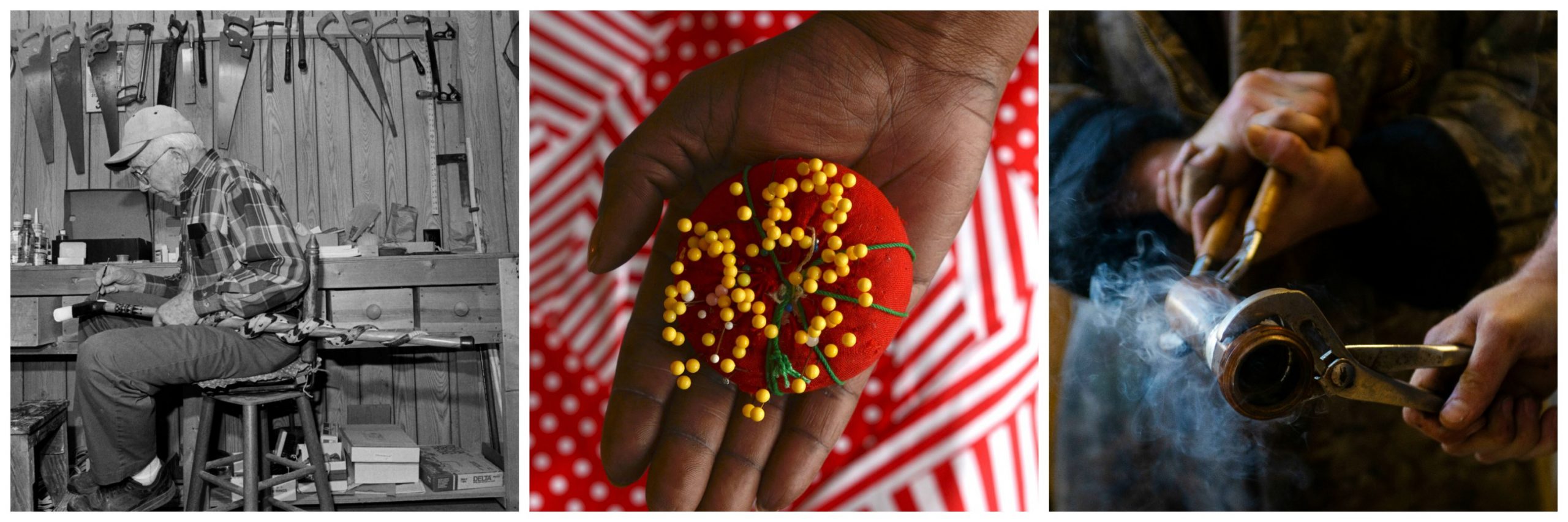

Recent educational work has focused on creating learning activity sheets, including one related to Real Folk, a special exhibit at the museum earlier this year. This activity sheet encourages children to find master artists or artisans in their family by talking to their parents, grandparents, and other relatives about special talents or skills they have or activities they enjoy doing, another route to learning more about your family.

Left: The exhibit panel “I Was There” includes text, images, and a short video recording the memories of the 1927 Bristol Sessions by Ralph Peer and several musicians. Center: Roni and Donna Stoneman, daughters of Ernest and Hattie Stoneman, share memories and stories with a member of the public at the 90th Anniversary of the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Right: The “Interview a Master Artist” activity sheet provides some prompt questions for discovering your family’s hidden talents. All images © Birthplace of Country Music

There are lots of articles and guides out there to help you tell and record your own family stories. Here are just a few that can help get you started:

- https://www.the-dispatch.com/entertainmentlife/20190929/how-to-tell-family-stories

- http://www.storyarts.org/classroom/roots/family.html

- https://www.familysearch.org/blog/en/18-writing-tips-tell-stories/

And if you want some inspiration, check out StoryCorps whose mission is “to preserve and share humanity’s stories in order to build connections between people and create a more just and compassionate world.” Over the years, they have recorded the stories of more than half a million people – from family stories to moments of history, from the small things to the big things in lives lived.

There are also tons of websites and books that will help you with some prompts to get the ball rolling on learning more about your family. Why don’t you try out a few of these questions at your next socially distanced family gathering?

- What is your favorite story about your grandmother/father?

- Where did you go to school, and what was your favorite subject?

- Did you ever play a musical instrument? Which one?

- Tell me about the places you have traveled.

- What was the best concert you attended?

- Did you play a sport in high school or college?

- What is YOUR favorite family story?

- Do you remember how you felt or what it was like when the Berlin Wall fell/Barack Obama became President/the Challenger space shuttle blew up – and, one day, when the COVID pandemic hit?

Finally, one last thing to remember: Family can be what you make of it – in other words, family stories can be those told by your relatives, but they can also be those told by the family you have created with your friends. All of these are part of your personal history and remembering them over the years will always bring you – and those you share them with – pleasure.

So start the conversation. Ask a few questions. Pull out some photographs to prompt the memories. Become the record-keeper and storyteller – for your family and friends!