On March 6, the museum opened a special exhibit called Real Folk: Passing on Trades & Traditions Through the Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Program, in partnership with the Virginia Folklife Program. While the COVID-19 situation meant that for three months no one was able to visit the exhibit – except virtually – we have now reopened, and the exhibit is waiting to be enjoyed through its closing date in August!

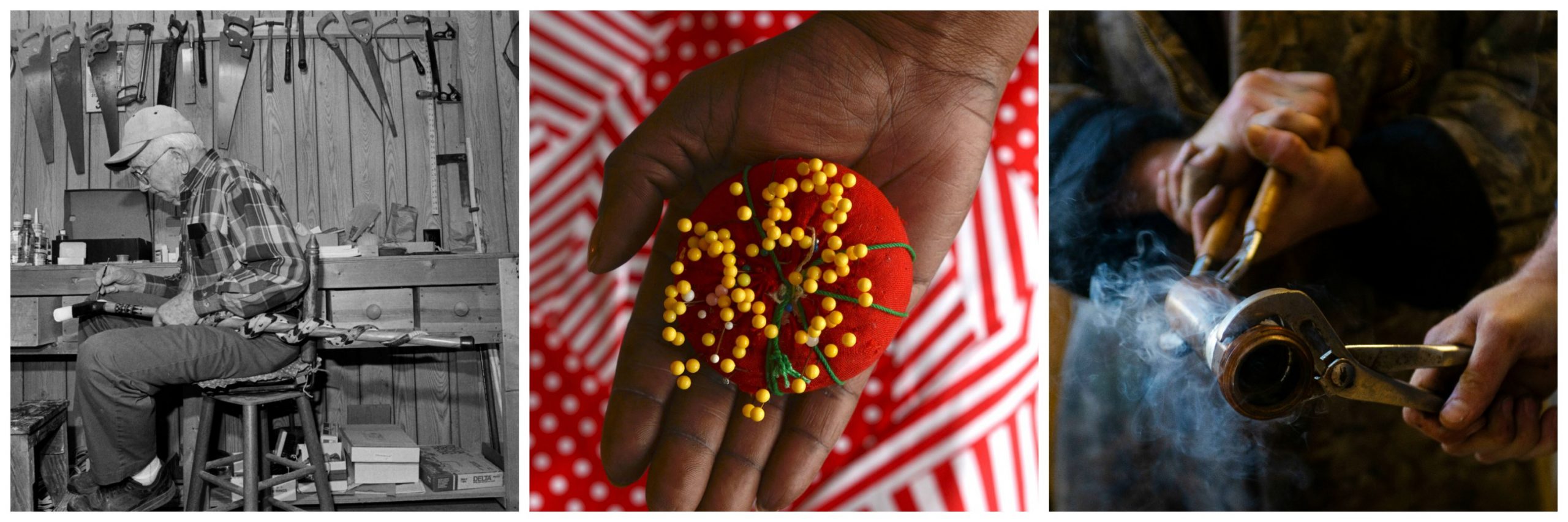

This is one of my favorite special exhibits that we’ve had on display at the museum – the images by photographers Pat Jarrett and Morgan Miller are stunning, the stories of the master artists and apprentices told by Virginia State Folklorist Jon Lohman are fascinating, and the range of crafts, trades, and traditions astounding.

Here are just a few of the interesting things I’ve learned from Real Folk:

A Virginia Town’s Salty Past

Saltville – found in the Southern Appalachians – is named for its unusually high number of salt marshes, or as locals call them, salt licks. Not only is the salt source extensive here, but the salt from Saltville is also especially salty – around 10 times saltier than ocean water! Saltville’s natural salt deposits have influenced the history of the region from the late Pleistocene period, when they attracted Ice Age mammals and Paleoamericans to the area, to early European traders to the Civil War when nearly two-thirds of the South’s salt was produced in Saltville and two bloody battles were fought here.

Jim Bordwine’s family has lived in and around Saltville since the 1770s. He has dedicated his life to educating the public about Saltville’s history and continuing its traditional craft of making salt, including passing down this knowledge to son Baron through an apprenticeship. © Birthplace of Country Music Museum

Quilt Signals

We have quite a few quilt connections in our museum – from the huge Birthplace of Country Music quilt hanging in our atrium to the quilt “tapestries” on sell in The Museum Store to the museum’s color scheme based on old quilts and flour sacks. Master Artist Sharon Tindall has conducted substantial research in support of the theory that African American quilts contained coded messages integral to the success of the Underground Railroad, codes that told enslaved people about what to expect next on their journey and how to find safe haven.

Sharon Tindall specializes in early African American quilt patterns and in working with fabrics that aren’t typically used in quilting, such as Malian mud cloth. She shared her experience with apprentice Nancy Chilton. © Birthplace of Country Music Museum

A Connection Between Music and Language

The đàn bâu – translated to mean “gourd lute” – is a monochord or one-stringed instrument, which plays a central role in Vietnamese music. Playing the đàn bâu can create microtones capable of imitating the six essential tones and variations of the Vietnamese language, nearly impossible to achieve with any other instrument. Traditionally, it is also used as an accompaniment to Vietnamese poetry readings.

Nam Phuon Nguyen began playing an instrument called the đàn bâu at 17, later touring and performing throughout the United States with her family. She is seen here with her apprentice Anh Dien Ky Nguyen. © Pat Jarrett/Virginia Folklife Program

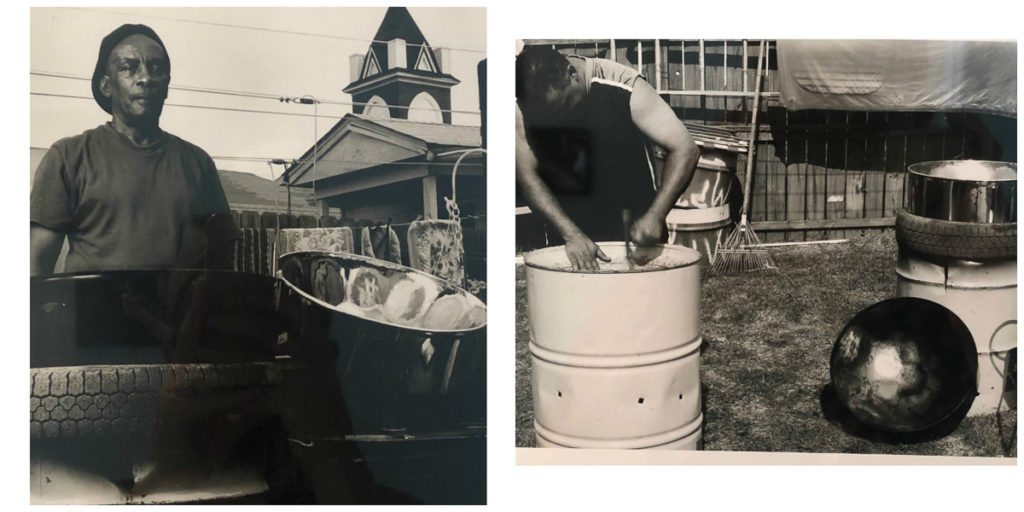

From Everyday Object to Musical Instrument

Music has often been made from everyday objects – for instance, think of a washtub bass or the spoons. The steel drum, or “pan” as it is called in the Caribbean, was invented in Trinidad around World War II, when island locals resourcefully crafted these instruments from oil drums left behind by the U.S. Navy. Contemporary pans are created when a 55-gallon steel oil drum is hammered concave, a process known as sinking. The drum is then tempered and notes are carefully grooved into the steel, resulting in a melodic percussive instrument that can play three full octaves.

Master Artist Elton Williams, who worked with apprentice Earl Sawyer, grew up in Trinidad and immersed himself in every aspect of steel bands. He is a musician, composer, tuner, and now one of the few steel pan makers in the U.S. © Morgan Miller/Virginia Folklife Program

For the Love of Fonts

Prior to the advent of photocopiers, short-run quick print, email, and social media, the local letterpress was the primary producer of the vast majority of materials for mass communication – from church bulletins to wedding announcements to commercial advertisements, and so much more. My favorite elements of letterpress are the individual letters used in the printing process (and so many possible fonts!) and the wonderful act of rolling out the ink ready to print. We have our own letterpress studio here in Southwest Virginia at the Burke Print Shop in the Wayne C. Henderson School of Appalachian Arts.

Left: Images from the letterpress apprenticeship between Garrett Queen and Lana Lambert in the Real Folk exhibit. Right: Letter blocks at the Burke Print Shop. © Pat Jarrett/Virginia Folklife Program; © Rene Rodgers

Different Dulcimers

When I used to think of a dulcimer, I thought of one particular type – an hourglass-shaped instrument – because we had one like that hanging in our home when I was a child. Since then, I’ve learned there are many types of dulcimers (all from the zither family) that are played in many places throughout the world – from the Appalachian or mountain dulcimer and the hammered dulcimer to the banjo dulcimer and the bowed dulcimer – with different shapes and different ways of being played. The dulcimer from my house – and the one most familiar around our area – is the mountain dulcimer, a fretted string instrument that first appeared in the 19th century among Scots-Irish communities. It is also known as the lap dulcimer.

Left: Phyllis Gaskins, seen here with apprentice Anna Stockdale, plays the Galax dulcimer, which is lozenge-shaped, has four strings all tuned to the same note, and is played with a turkey or goose quill. The Galax dulcimer is intended to be an equal instrument in old-time string bands, mirroring the fiddle. Right: Master Dulcimer Maker Walter Messick apprenticed Chris Testerman, an award-winning fiddler who is already considered one of the great up-and-coming luthiers in the region. © Pat Jarrett/Virginia Folklife Program

An Unorthodox Route to Creativity

The late Pastor Mary Onley, known as “Mama-Girl,” was a self-taught artist who came from generations of farm laborers, working in the fields herself at the age of 12. Severe allergies resulted in several hospitalizations, and during one of these, she reported being visited by a spirit who instructed her to create art out of paper and found objects – something she had never done before. She went on to become one of the most celebrated folk artists on the East Coast, creating lyrical newspaper and glue sculptures that reflected her inner visions and unique creativity.

In 2016, Mama-Girl taught son David Rogers her unorthodox artistic techniques and how to open his mind to receive his own divine artistic inspirations. © Pat Jarrett/Virginia Folklife Program