By Sam Parker, AV & Technology Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

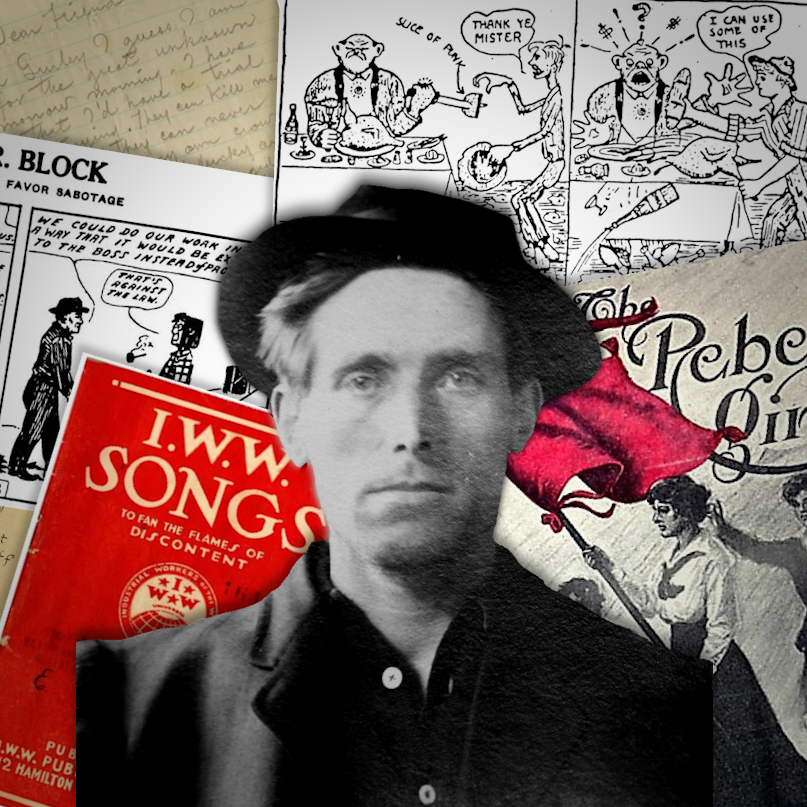

Protest and labor have been common themes of American folk music for a long time. Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Phil Ochs are all notable for their recordings of old union ballads and folk tunes, as well as the many songs they each wrote detailing the struggles of America’s poor and downtrodden. One musician penned nearly thirty songs and poems within the span of just four years that remain in the American folk lexicon to this day. In the century after his death, he’s been remembered as a troubadour, a rebel, and a martyr. His music has been sung by numerous artists for decades, and tributes to him have been performed by artists such as Billy Bragg, Paul Robeson, Bruce Springsteen, and most famously Joan Baez at the 1969 Woodstock Music and Art Fair. To commemorate May 1st – known around the world as International Workers’ Day – let’s dive into the life and music of Joe Hill.

Joel Emmanuel Hägglund was born in Sweden in 1879. His father died when he was just nine years old, a tragedy that forced Joel and all of his siblings out of school and into the workforce. As a child laborer, Joel worked in a rope factory and later as a stoker for a steam-operated crane until his mother passed away in his early twenties. After her death, the six Hägglund siblings decided to sell the family home and went their separate ways. Joel and his brother Paul emigrated to New York, and from there he traveled with the millions of other itinerant workers thronging the nation’s cities, farms, and railroads.

As Joel walked and train-hopped westward, his hopes of America being a land of wealth and opportunity quickly faded. He lived and worked among the deep wealth disparity that dominated the receding Gilded Age of the United States, working for dollars a day and facing discrimination as an immigrant. By the time he reached San Francisco, Joel was going by the name “Joseph Hillstrom,” later shortened to “Joe Hill,” likely to protect himself from anti-union blacklisting. By this time, Joe had become a “Wobbly”, a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a labor union rising in both membership and notoriety at the time.*

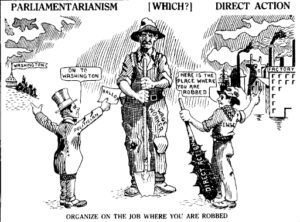

The IWW differed from other unions of the period. They advocated for One Big Union across all industries, workplace democracy – where workers collectively decided on pay and conditions, and vehemently opposed scabbing – when workers cross a picket line to fill jobs left by those on strike. They advocated for direct action, valuing strikes and sabotage to force rapid changes over gradual reforms through political avenues. These characteristics led Wobblies to be called radicals, and anyone carrying the IWW’s little red membership card was viewed as a troublemaker and rabble-rouser.

Since childhood, Joe demonstrated musical talent, which he continued to do when he became a Wobbly. Joe often wrote lyrics set to the melodies of popular songs, including “The Preacher and the Slave,” which is set to the tune of “In the Sweet by-and-by.” This song attacked the Salvation Army, which IWW members referred to as the “Starvation Army,” for focusing on workers’ spiritual rather than their material well-being. The song even coined the phrase “pie in the sky” with its lyrics.

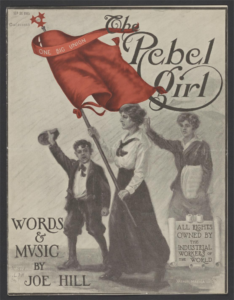

One of Joe’s most famous songs is “The Rebel Girl,” which he wrote for fellow Wobbly and suffragette Elizabeth Gurley Flynn to expand IWW recruitment among women. Joe believed the organization was incomplete without the representation of working women. In the Wobbly newspaper Solidarity, Joe wrote that without women, “We have created a kind of one-legged, freakish animal of a union.” In 1990, Hazel Dickens, another musician and activist, recorded the song for the Smithsonian Folkways album Don’t Mourn, Organize! Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill.

Joe also wrote a song for “Mr. Block,” a cartoon character appearing in the IWW’s newspaper. Mr. Block is a literal blockhead meant to represent workers tricked by capitalism and patriotism, or sometimes who just belonged to the wrong union. Many comic strips involved Mr. Block praising the United States, hoping he’ll get rich if he works hard enough, or decrying the IWW’s radicalism, only to end up unemployed, destitute, injured, or a combination of the three. Almost all of Joe’s songs had political undertones. He saw music as the best way of reaching other working-class people, as he wrote: “A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over. And I maintain that if a person can put a few common sense facts into a song and dress them up in a cloak of humor, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read.”

During the night of January 10th, 1914, Joe arrived on the doorstep of a Salt Lake City doctor, bleeding from a gunshot wound. He claimed it was from an angry husband, but across town, local police had been investigating the shooting of a former policeman. One of the shooters had been wounded, and this was enough for the police to pin the crime on Joe. Though no witness could identify Joe conclusively, and the murder weapon was never recovered, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. Joe chose to be executed by firing squad, remarking, “I have been shot a few times in the past and I guess I can stand it again.” While in Prison, he wrote to one of the IWW founders, Big Bill Haywood: “Goodbye Bill: I die like a true rebel. Don’t waste any time mourning, organize! It is a hundred miles from here to Wyoming. Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don’t want to be found dead in Utah.”

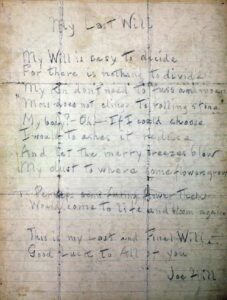

Joe wrote a short poem on the day of his execution, requesting to be cremated and his ashes spread. While blindfolded and tied to a chair, Joe shouted the order to fire himself. There was a small service in Salt Lake City before his remains were moved to Chicago, where thousands of supporters listened to his songs and followed his casket to the cemetery where he was cremated. His ashes were divided up and mailed to IWW locals and supporters across the globe – Utah was exempted per his wishes. Most were spread in the wind, while other parcels were collected, confiscated, and in a few unusual cases even consumed.

Joe Hill’s musical legacy didn’t die with him. After his death, poet and screenwriter Alfred Hayes wrote the poem “Joe Hill,” later put to music by Earl Robinson and performed by artists such as Paul Robeson, Joan Baez, and Bruce Springsteen. The song tells of a vision of Joe Hill visiting the narrator in their sleep. The ghost’s message echoes his final letter to Bill Haywood: Don’t waste any time mourning, organize!

Some Labor/Protest Musician Museums in the US to check out:

National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum

West Virginia Mine Wars Museum

*For more on a 1916 strike the IWW was involved in check out our interview with the American Labor Museum from 8/15/2024 on Museum Talk!