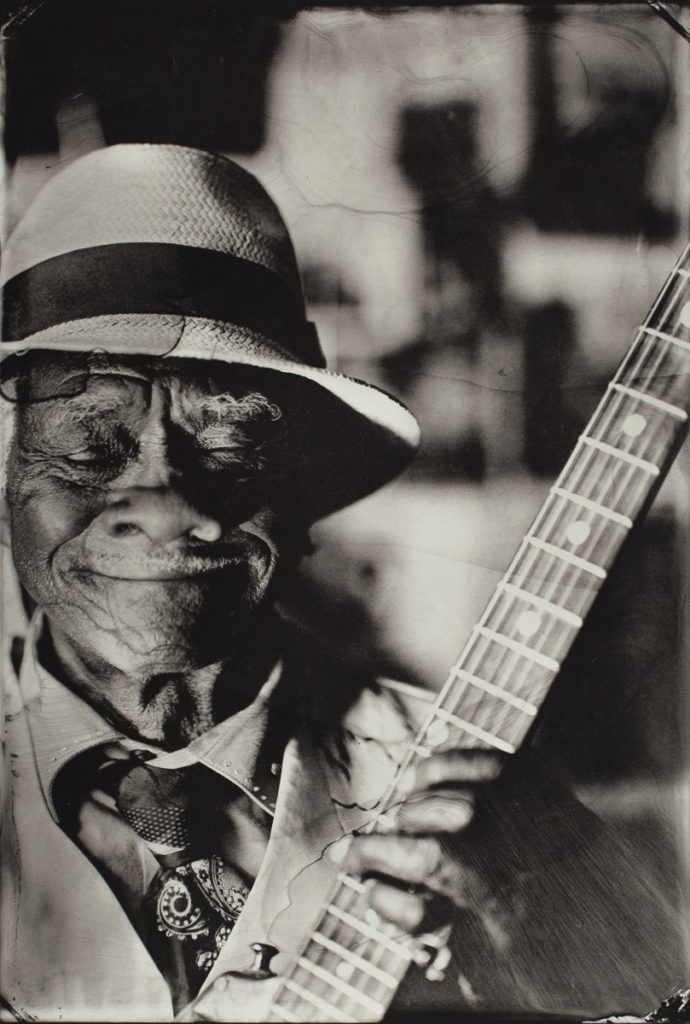

In our current special exhibit, Our Living Past: Platinum Portraits of Southern Music Makers, Timothy Duffy of the Music Maker Relief Foundation uses a photographic technology that was most popular in the late 19th century to photograph roots musicians today. The method he uses is most commonly called tintype photography, a form of wet-collodion photography that is quite complicated compared to modern photographic methods. So why does Duffy use this historic technique instead of a modern process?

Before we try to answer that, let’s explore what a tintype photo is and how it is made. Tintype, also called ferrotype, is one of the earliest forms of photography. Developed in the 1850s, this wet-collodion process requires a very large camera, a dark space, a plate, and a good understanding of chemistry. Once exposed, a direct positive image is created on a sheet of metal. This means there are no negatives of the image to make copies from, and so each tintype is completely unique!

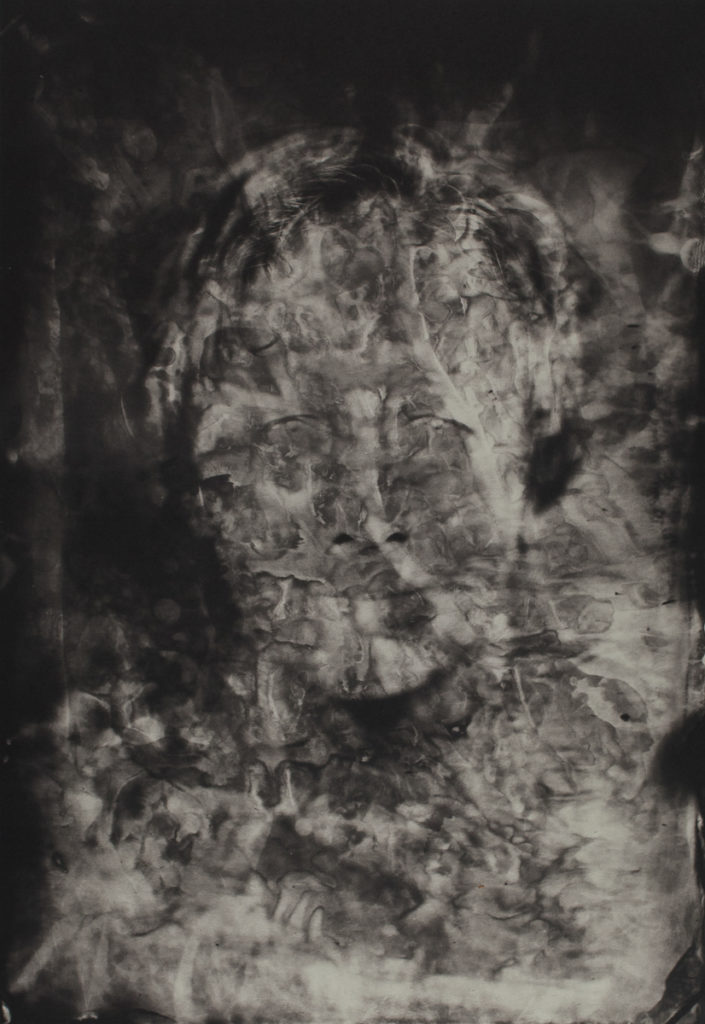

Making a tintype is a complicated multi-step process where minor variations such as drying too quickly, light oversensitivity, or slight ripples in the surface of the chemistry can create errors in the final image. However, these “mistakes” are often what give these images their unique beauty. Many modern artists like Duffy sometimes intentionally play with these “mistakes” to create uniquely interesting photos!

What made tintypes stand out compared to other photographic methods of the age, such as ambroytypes or daguerreotypes, was the use of an iron plate instead of a glass one. The iron plate is where the name ferrotype comes from. Though the resulting images weren’t made of tin as the name would suggest, the term was commonly used, based on the cheap or “tinny” feeling of the photos that eventually became the primary identifier of the method. Because tintypes use an iron plate they are much more durable than images printed on glass. They were also less expensive to produce, and the finished product did not require additional, often expensive, protective casing.

In addition to their durability and affordability, tintypes were faster than previous methods. From start to finish the entire chemical process had to be completed in 15 minutes! These three features – speed, durability, and affordability – quickly helped tintypes become the most popular form of photography in the late 19th century.

For the first time photographers could easily travel and take instant photographs for customers at events such as fairs and in both rural and urban settings. Photographers traveled out west where they recorded images of cowboys and covered wagons. They documented the Civil War, shocking the country with horrific images from battlefields as well as preserving the memory of individual soldiers for loved ones.

These special characteristics also made photography more accessible to a wider range of people. The popularity of tintype photography also coincided with the Emancipation Proclamation and end of the Civil War, meaning that for the first time African Americans were able to have their photographs taken in large numbers.

Photograph courtesy of Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Unfortunately, the same characteristics that encouraged widespread use also encouraged a lack of record-keeping. Because they could be created in a single sitting and given to the sitter or their loved one without excessive packaging, tintypes were frequently not documented with the name of either the sitter or the photographer. This means that although there are a large number of surviving tintype images that remain today, the stories behind them have all too often been lost.

Today, most of the people Duffy photographs are not what we would regard as famous within our celebrity-driven society. Often the sitters for his images are known within their communities but perhaps not far outside of them. However, they all have stories with deep roots and stories that beg to be shared. These musicians want to be remembered, and Duffy strives to ensure they will be. His tintypes take a small step toward correcting the past by documenting the present using a method that has historically given so many underrepresented people their first opportunity to document themselves for posterity.

Duffy’s process is not just taking a photograph – it’s also a theatrical event! Modern cameras can take hundreds of photographs in a minute. Duffy takes an hour to properly get just one photograph. Once he has his shot set up, the moment is captured instantly, and it cannot be retaken easily. In addition to the stress of getting it right on the first try, the studio itself can be intimidating. The giant camera glares at the sitter, and when combined with an extended blinding light, it can feel like the world has stopped for a moment. But these musicians do not shy away from the lenses. They are true performers and are not intimidated by the camera but rather seem to confront it and come out triumphantly.

Roots musicians connect us to the past through music by carrying on these traditions and skills. Modern tintypes do something similar by challenging our sense of time visually. Duffy bridges this gap by using one to propel the other, and in the process, he shows us a new side to both.

The Our Living Past special exhibit will be on display at the museum through September 30, 2021. We are also hosting a concert performance by Pat “Mother Blues” Cohen on Saturday, September 25 at 7:00pm.

Erika Barker is the museum’s Curatorial Manager.

© Birthplace of Country Music Museum; photographs on loan from Nina Rizzo