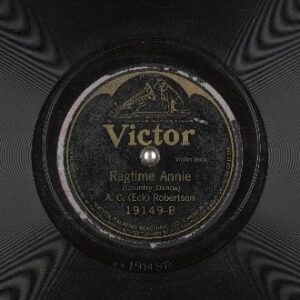

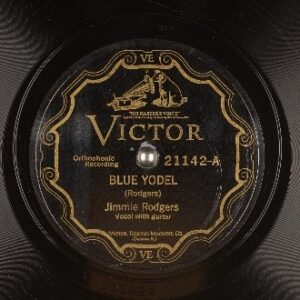

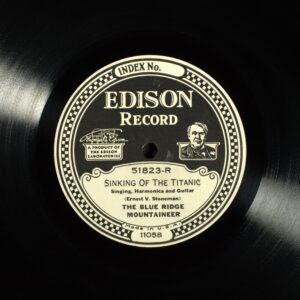

A lot of quality time can be spent in the 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings section of archive.org, especially if you are old enough to remember 78s or just love exploring old music. One striking thing about the site is how the quality of these recordings gets much better after 1925. Click on the record labels below to hear the difference.

The technology behind this change in sound quality goes a long way toward explaining why the Bristol Sessions were such a success. In fact, an argument can be made that the Bristol Sessions had to happen after 1925 and before 1930, or they would not have happened at all.

The first device to record sound and play it back was the phonograph invented by Thomas Edison in 1877. Recordings were made on wax cylinders that were sold with the recording machines. These early machines were mostly marketed as dictating machines. During the 1890s some musical recordings were created one at a time and sold to nickelodeons to be played on primitive jukeboxes, but there was no practical process for mass-producing music recordings until after 1900, when Emile Berliner perfected a record player that played discs (instead of cylinders. The signing of opera star Enrico Caruso by Berliner’s Victor Company has been cited by many as the event that launched the modern recording industry (Caruso’s 1904 recording of Vesti la giubba sold a million copies).

In those days masters for commercial recordings were created by musicians who sang or played in front of a large metal horn that funneled sound waves to a vibrating diaphragm. These vibrations were transferred to an attached stylus that etched the sound waves onto a master wax disc. Adjustments to the balance and tone of these purely acoustic recordings could only be made by positioning the musicians. The sound quality was compromised by the narrow frequency range that could be captured (100 to 2500 Hz), and the low volume level of the recordings severely restricted the dynamics.

Even given the compromised sound quality, acoustic phonographs and records were popular. Jimmie Rodgers bought a phonograph in the early 1920s. His wife Carrie later recalled that Jimmie bought records “by the ton” despite their marginal household income. Maybelle Carter’s husband Eck was a U.S. mail clerk, the “best job in the Valley” and loved buying gadgets of all kinds. He was a classical music buff and had a large record collection.

Nevertheless, the poor audio quality of acoustically recorded phonograph records hurt sales, especially starting in the mid-1920s when people started buying radios.

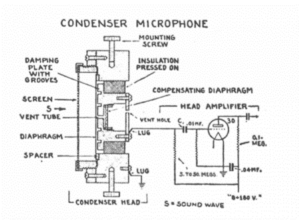

Things changed dramatically when Western Electric, the laboratory complex for the Bell Telephone company, developed the “Westrex” system of electronic recording that used condenser microphones. A condenser microphone consists of a diaphragm and a metal plate that creates an electronic signal. The electric sound produced by this system had a greatly expanded frequency range of 60 to 6000 Hz, and the volume could be boosted by the then-new vacuum tube amplifiers.

Western Electric licensed this revolutionary technology to the two leading American recording companies, Victor and Columbia, in 1925. Victor’s “Orthophonic Victrola” was the first consumer phonograph designed to play electrically recorded phonograph records.

This new technology was a sensation. The entire U.S. record industry had a profit of $123,000 in 1925. In one week in 1926 Victor sold $20 million worth of Victrola players.

This new technology made the Bristol Sessions possible. A giant horn was no longer necessary to make recordings. This meant that musicians no longer had to travel to Victor’s headquarters in New Jersey or other large cities for recording sessions. The recording equipment could more easily be packed into suitcases and transported anywhere a train or truck could go. This notably included places like rural Tennessee and Virginia, where musicians making country, then called “hillbilly” music, lived.

The electronic recording boom of the late 1920s was short-lived. The stock market crashed in October of 1929, which triggered the Great Depression of the 1930s. U.S. record sales went from $104 million in 1927 to $10 million in 1930. This also applied to record sales from Bristol Sessions artists. In his biography of Ralph Peer, Barry Mazor observed:

[Jimmie] Rodgers’ fairly dependable sales in the high-flying half-million-copy neighborhood were over; five to ten thousand copies sold had become the new “good,” and as early as spring 1930 Peer would need to reassure Jimmie that “on a percentage basis your stuff sells at least as much as anybody else’s. In other words, you are still at the top of the heap, but the heap isn’t so big.’”

Although the record sales dropped precipitously, some Bristol Sessions artists, such as Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family, managed to continue selling their music despite the struggling economy. Many others, such as Ernest “Pop” Stoneman, did not record much, if at all, during the Great Depression.

The advent of the Western Electric microphone and Orthophonic Victrola in 1925 directly affected the success and influence of the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Had the sessions taken place after 1930, the Great Depression would likely have hindered the success of the records regardless of the technology used or talent recorded. The “Big Bang” of modern country music ignited when Ralph Peer’s business know how, the talent of the artists who recorded, and the technology that more accurately captured the music all came together in Bristol in 1927.

By Ed Hagen, Gallery Assistant and guest blogger