The 1927 Bristol Sessions story is one of developing technology, star singers, and business acumen. It’s also a very personal story for the descendants of those artists who answered Ralph Peer’s call for musicians and recorded in that makeshift studio in the Taylor-Christian Hat Company here in Bristol.

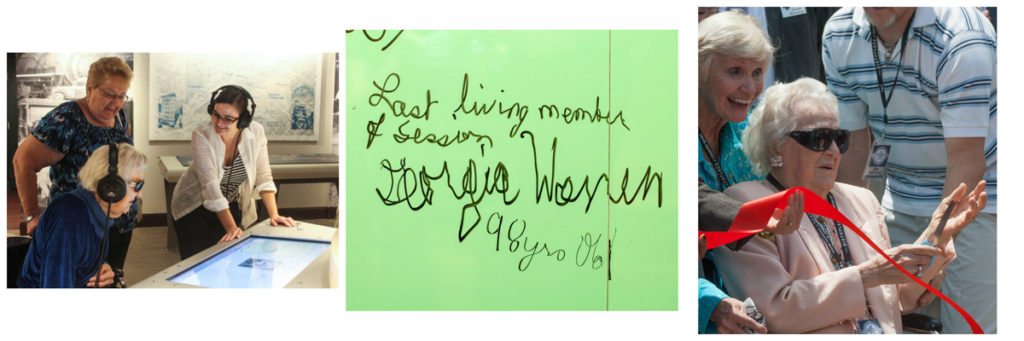

One of those Bristol Sessions artists – Georgia Warren – holds a particularly special place in our story as she was here with us at the museum’s Grand Opening in August 2014, the last surviving musician from those historic recordings. When she came to Bristol in 1927, she was only 12 years old, the daughter of George Massengill, who was the leader of a congregational choir from Bluff City, Tennessee. Known as the Tennessee Mountaineers, they recorded two songs at the Bristol Sessions: “Shall We Gather at the River” and “Standing on the Promises.”

Georgia Warren passed away on March 6, 2016 at the age of 100. And so today, the anniversary of that date, we want to remember her and her part in our story. Because we actually knew Georgia, and know her family, we have had the chance to learn about the things she loved, about her life, about what singing in that dark studio all those years ago meant to her. And we’ve had the chance to learn what Georgia’s place in this history means to her family too.

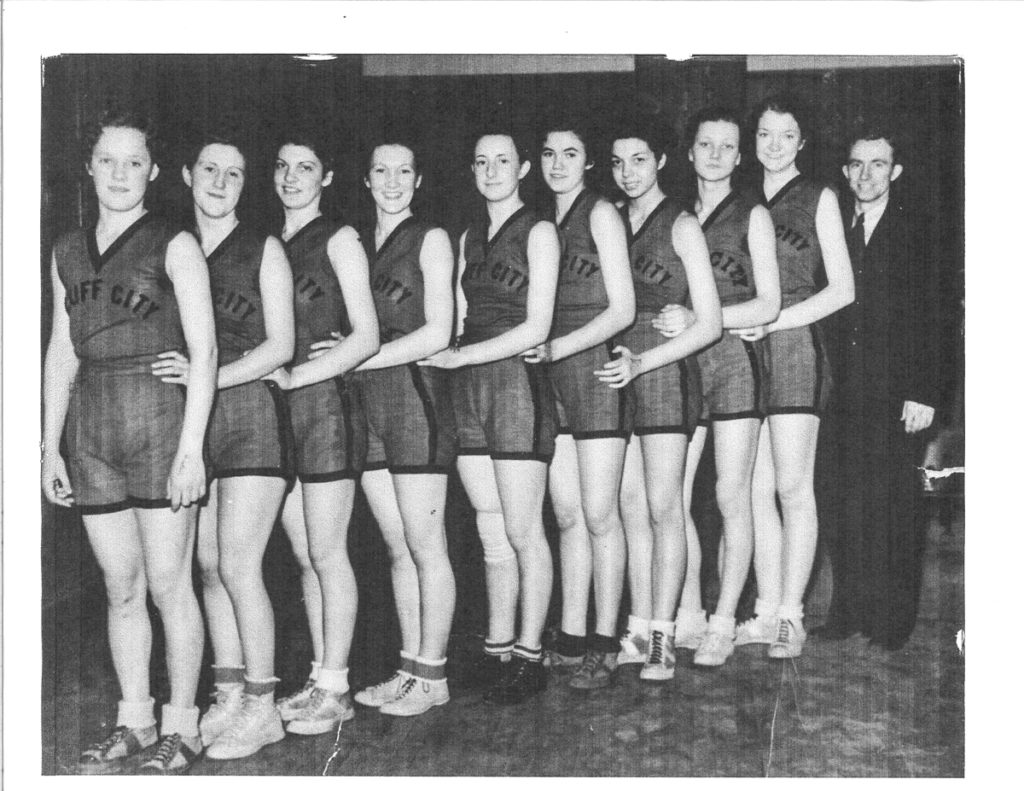

Some things we learned were surprising – for instance, Georgia played basketball in high school and won MVP in 1934 when her high school team won the local championships. She kept her love for basketball in later life as a huge fan of the Lady Vols and Pat Summitt, often saying that Pat should have been the men’s coach at University of Tennessee too. (Something probably quite a few Pat Summitt fans have said in the past!)

Others – like her green thumb – made more sense, knowing that Georgia grew up on a farm in rural Tennessee. After marrying her husband Paul and living in California for a while, they moved back to Tennessee to build a farm on a parcel of land – with Georgia right there in the thick of it driving the tractor, baling hay, planting tobacco, helping with the animals, and growing vegetables. Her daughter Nancy Taylor remembers sitting under a tree in the yard of their house, breaking beans with her mother, and how her mother did a lot of canning of fruit and vegetables, stocking their pantry with row upon row of Mason jars filled with food. Georgia was also a keen flower gardener, filling her yard with a bounty of beautiful flowers and especially loving the first crocuses as they bloomed each year.

Even though Georgia’s appearance on the two Tennessee Mountaineers sides from the Bristol Sessions was her one and only professional performance, music and singing was still a big part of her life. For many years, she continued to sing (alto) in the First Christian Church in Bluff City, Tennessee, along with her parents and her husband (tenor), while Nancy’s sister played piano and organ. Georgia’s father George Massengill was one of the originators of this church, though before it was made of brick and mortar the congregation often gathered on Massengill’s front porch to sing, and Nancy remembers her grandfather saying that people would yell out song requests down the holler because they could hear them from afar. The family also used to sing together just for fun – as Nancy tells us, “We’d have a big time singing different songs,” from Elvis’s “Love Me Tender” to singing along with the record from the Sessions.

A connection to the music she sang in 1927 stayed strong through the years, and when Georgia was ailing toward the end of her life, the hospice minister would sing “Shall We Gather at the River” with her at home – apparently she knew it by heart, never missing a note or a word of the song. And at her funeral a couple of years ago, the Tennessee Mountaineer’s 1927 rendition of “Shall We Gather at the River” was played in the funeral home chapel with everyone singing together to honor Georgia.

Nancy tells us that Georgia felt enormous pride from the part she played in the 1927 Bristol Sessions recordings, and that the recognition of this history was important to her. She didn’t want to have a fuss made over her, but she enjoyed telling people about climbing the dark stairs to the put-together studio, seeing Peer and the engineers, and being a bit scared by the whole set up, staying close to her father but still singing strong and true. And the best part – seeing Jimmie Rodgers, who recorded the previous day, and thinking he was quite handsome!

Nancy notes that the songs the Tennessee Mountaineers sang at the Sessions were old standards, not really sung much anymore but the kind of music she and her mother were raised on. And Georgia’s story underlines one of the fundamental truths about the Sessions recordings: many of the songs recorded were everyday sacred family songs, songs sung in church and at home, and most of the artists were working people who went back to their everyday lives after the recordings. And that’s part of what makes them special.

When asked what her mother’s place in the history of the 1927 Bristol Sessions means to her, Nancy said, “Even though she’s gone, I don’t want them to forget her.” There’s no fear of that here at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum – Georgia’s story is our story and the personal connection makes our appreciation of this history richer.