Today is the anniversary of A.P. Carter’s birth – he was born on December 15, 1891 in Maces Spring, Virginia. A.P. was the driving force behind The Carter Family, and his place in music history is strong and true. Numerous books and articles chronicle the Carters’ musical journey and their legacy and impact – my personal favorites are Mark Zwonitzer and Charles Hirshberg’s Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone and David Lasky and Frank Young’s graphic novel The Carter Family: Don’t Forget This Song. Their story has also been told through television, radio and film – from Ken Burns’ Country Music documentary series to The Winding Stream by Beth Harrington.

A blog post does not seem sufficient to explore the full life of A.P. Carter, but we wanted to celebrate this special day and so I’ve instead pulled together five interesting details from A. P.’s story.

Lightning Strike

A.P. was full of quirks – from his daydreaming to his wandering ways to the tremor he carried with him his whole life. A.P.’s mother Molly Bays Carter attributed her firstborn son’s shaking to a thunderstorm she encountered one day when she was pregnant with him. She was standing under an apple tree when lightning struck, the energy traveling down to the ground and all around her – as Zwonitzer and Hirshberg report, Molly always said that this lightning strike “shot such a bolt of fright into her swollen belly that the baby inside would be afflicted with that very nervous energy for each and all of his days.” The tremor that affected A.P.’s body also came through in his voice, which carried a bit of a quaver when talking and singing. And the nervous energy seemed to push A.P. to always be on the move, hitting the road for days on end, and keeping his mind busy and turned inward.

All in a Day’s Work

While A.P.’s dream was to make money from music – a dream that he, with Sara and Maybelle, fulfilled – that wasn’t the only work he did. As with so many people during the early part of the 20th century, working hard, and doing a multitude of jobs, was a necessity to take care of family. When A.P. met Sara for the very first time, he was a traveling fruit tree salesman. (Incidentally, he was so struck by Sara – and her singing voice – on this first meeting that he bought from her rather than the other way around; he went home with an order for a set of dishes.) He also farmed his land and worked sawmills at various times, and then after his music career came to an end, he set up a grocery store in Maces Spring, though from all accounts he didn’t keep regular hours and his business wasn’t as brisk as he would probably like. However, his store served as a gathering place, and one imagines a place where music was made, perhaps leading him on to his dream of a permanent home for music-making, fulfilled in his daughter Janette’s establishment of the Carter Family Fold after A.P.’s passing.

A.P. Carter’s grocery store, now a museum devoted to The Carter Family. © Southern Foodways Alliance

A Way with Words

A.P.’s penchant for wandering in his search for new (old) songs is well known – a habit referred to as “songcatching.” Along the way, A.P. went back into the hills of Appalachia and into the factories in the urban areas, always on the hunt for a song he hadn’t heard before. He didn’t always go on this search on his own, and his songcatching travels with African American musician Lesley Riddle are also a familiar element of the Carter history. A.P. met Lesley, also known as “Esley,” in Kingsport, Tennessee – initially as a source of good songs to learn. Soon they were traveling together, which must have been challenging as they passed down the roads and into the towns of a segregated South. Often A.P. had to find a separate place for Lesley to stay and eat, either with friends, family, or others who didn’t discriminate based on the color of his skin. Lesley had a head for remembering the tunes and lyrics of the songs they heard, acting like a “human recorder” in some ways, and they spent a lot time going over the songs they brought home and working them up with Sara and Maybelle. Lesley noted that there were times when he’d have to get up and walk away just to have a break from that intense focus. But all that songcatching led the Carters to a wonderfully huge and varied repertoire, including songs A.P. wrote himself, a discography that is one of the most influential in country music history.

A.P.’s Guitar

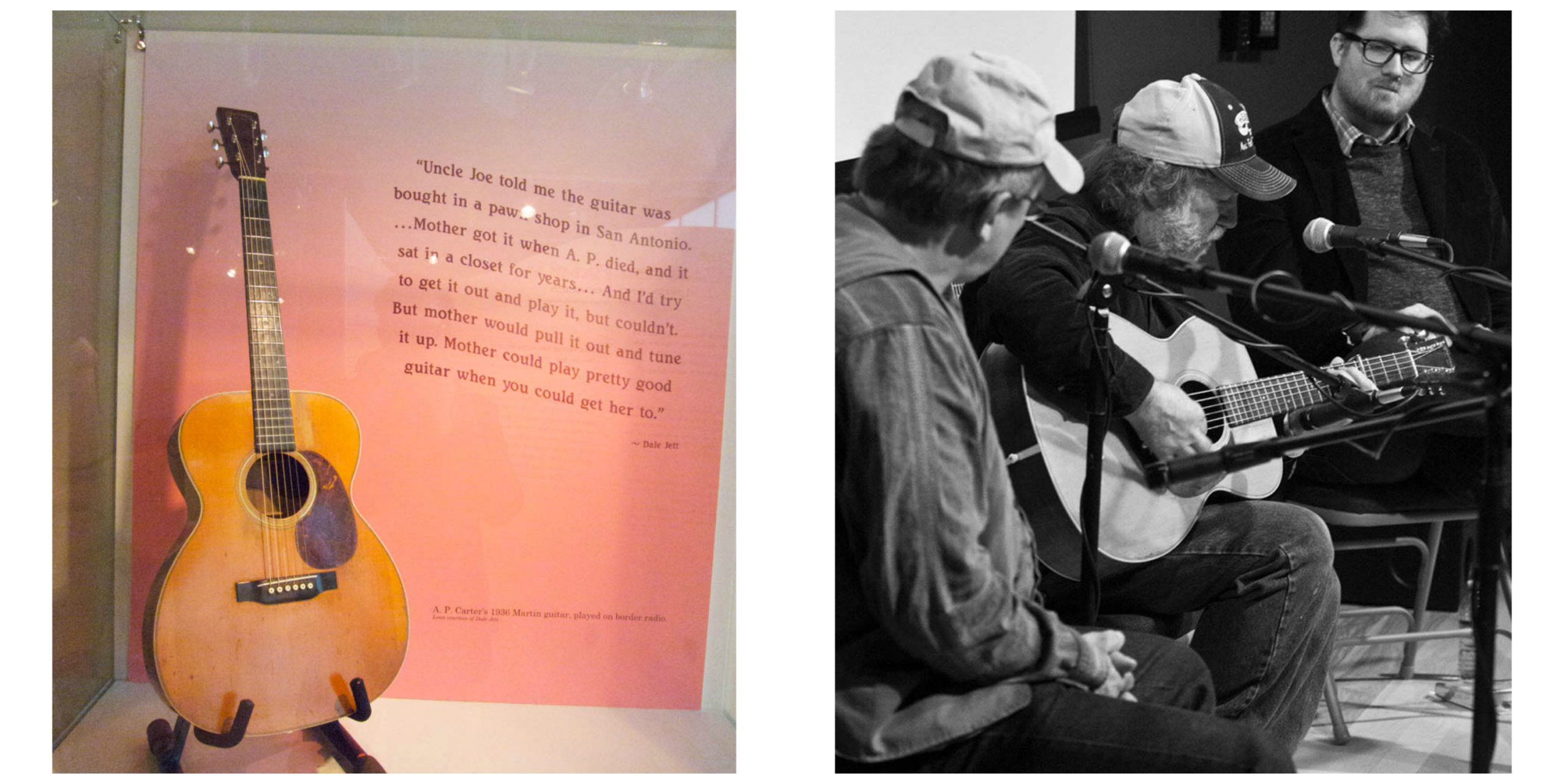

The museum was fortunate to have a piece of A.P.’s musical career on display a few years ago at our first special exhibit, The Carter Family: Lives and Legacies. On loan from his grandson Dale Jett, A.P.’s 1936 Martin 000-28 style guitar had a story to tell. A.P. bought this guitar in a pawn shop in San Antonio or Del Rio, Texas for $65–$75 dollars. In the 1930s, Martins were being made out of the best materials with the best craftspeople – all handmade rather than by machines, and this guitar’s top was made from spruce found in the Appalachians and considered the best tone wood. While A.P. isn’t really known for his guitar playing and he certainly didn’t play an instrument too often for The Carter Family performances or recordings, he did play this Martin on border radio from time to time, and it can be seen in a promotional Christmas card from this period that featured the musical family. The guitar is still played today by Jett.

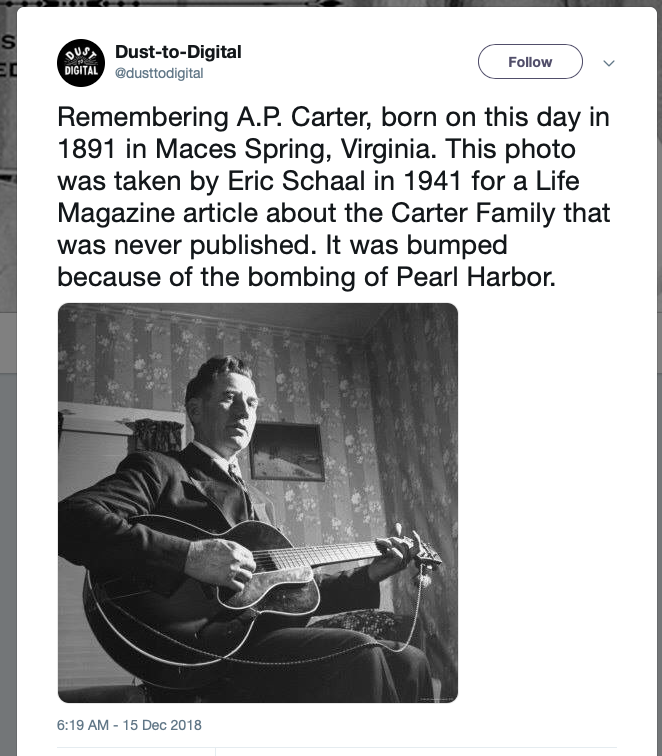

1941

So much of life is down to the vagaries of chance, and A.P.’s story is no different. The Carters’ place in country music – indeed, in American music as a whole and beyond – is significant. But their story still has a “what if” element, and that comes from the Life Magazine photo shoot that happened in the fall of 1941. Focusing on the original Carter Family and their children, the photo shoot took place in Virginia with the intention of a story about the Carters and their music appearing in the magazine later that year. However, the photo spread never appeared as it was pushed off the pages by the bigger news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The photographer Eric Schaal did keep one of the images – a portrait of himself with A.P. – framed in his home, later saying that A.P. “was the most exotic subject he’d ever photographed.” And so the question remains: What would have happened to the Carters, and to A.P., if that spread and their story had been published to the wide and varied audience found in the readership of Life?