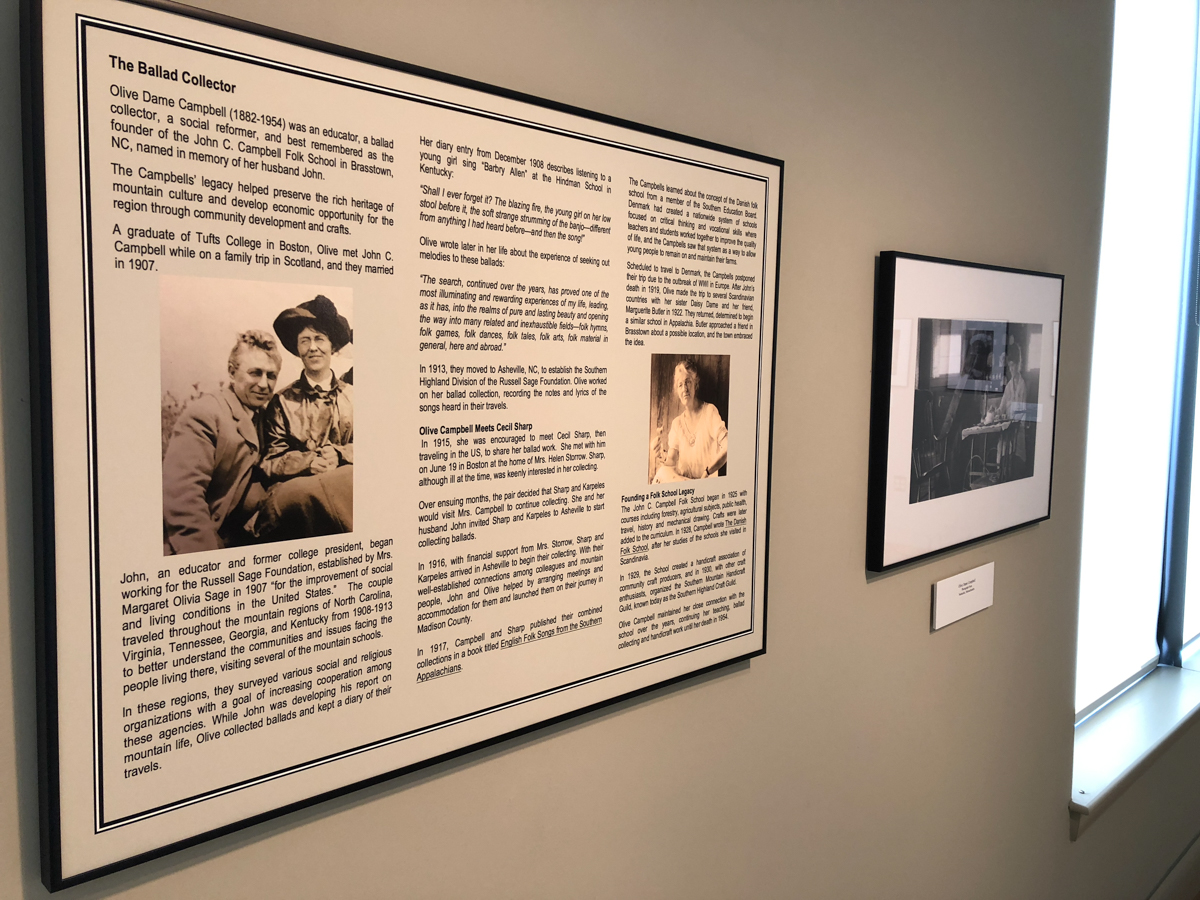

Olive Dame Campbell appears sometimes as a ghostly figure in the world of folk music: half champion, half a forgotten footnote. She came to our attention by different routes. While undertaking her PhD in Ethnography in Newfoundland, Wendy met her as a strong feminist icon doing great work; Jack discovered her as we prepared to teach ballads and folktales at the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, North Carolina, a few years ago. Olive had established the school in memory of her late husband, and they had both been involved in establishing settlement schools in Appalachia in the early 1900s.

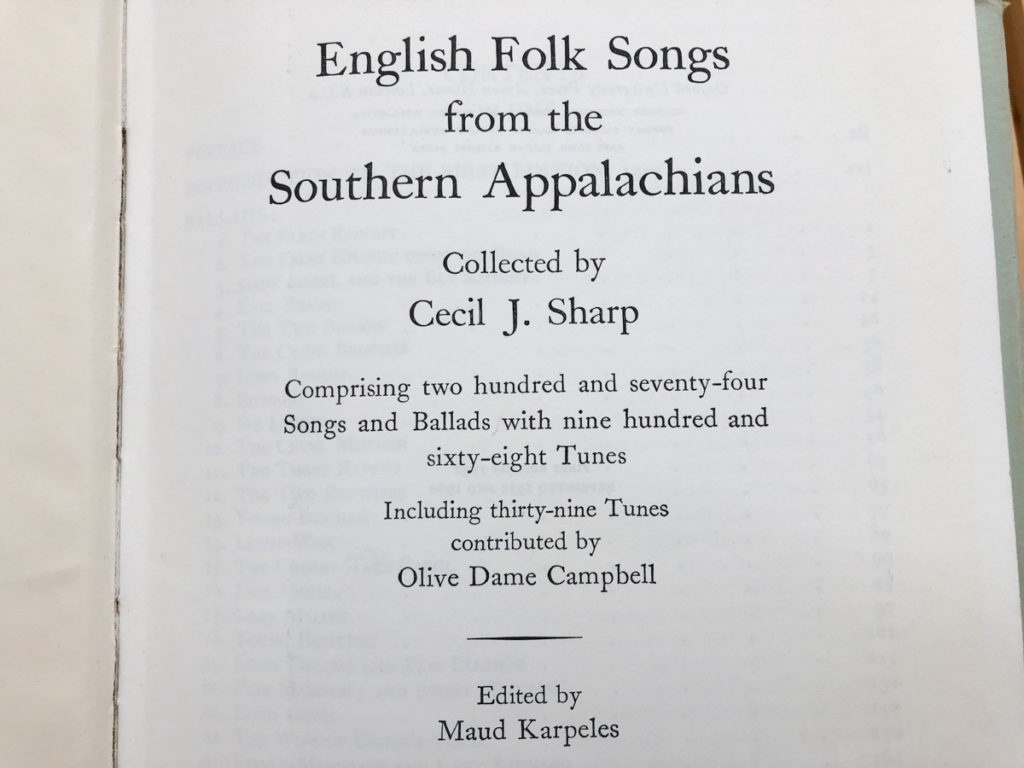

Olive first encountered Appalachian ballads and fiddle tunes as she and John began their good works, and a little sidetracking goes a long way – Olive was the first to start collecting the old mountain ballads that had migrated from Scotland and England via the Scots-Irish pioneers, and she also created a manuscript collection of words and music. Experts debate how her work came to the attention of the famous English folk song enthusiast Cecil Sharp, who came to the Appalachians to do similar work in 1916 to 1918 and, with his secretary Maud Karpeles, built on the collecting work done by Olive. Eventually this combined work would be published as English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians; however, since its publication, the collection has mostly been referred to as Sharp’s work – rarely do we see Olive given much credit beyond her name in small print on the book’s title pages.

Until Hollywood got hold of the story, that is….

The lead character of a movie called Songcatcher was loosely based on Olive Dame Campbell. The film focuses on the mountain music of Appalachia and uses many very fine local musicians in supporting roles, including Sheila Kay Adams and Phil Jamieson. In the final scene, as the ballad collector heads down the mountain to conquer city life with her new Appalachian family, they meet an English gentleman headed up. He is obviously based on Cecil Sharp.

It was seeing Songcatcher that rekindled our interest in someone we felt should be better known. It may be that she was rather sidelined simply because she was a woman carrying out studies at a time when men were seen as more ‘serious’ academics. It’s certainly interesting how difficult finding information about her song collecting can be. Internet searches divert to information about her husband or Sharp. She does have a page on Wikipedia, but once again it’s mostly about the men in her life.

When we make musical presentations, we like to point out that most tradition bearers are women, in music and song as well as in story and dance. Women are frequently the sources of the ballads, the stories, the recipes, the remedies, etc. How often has an archived recording of home visits featured a male source breaking down in the middle of a ballad, only for the sister, wife or mother to shout the next line from the kitchen where she is preparing food for the guests who have come to record the singer?

The series of books that we lent to the museum for its current exhibition, The Appalachian Photographs of Cecil Sharp, span 1700–1950. All are published by men, although their song and ballad sources are mostly women. Sir Walter Scott got the majority of his ballads from ‘Mrs Brown of Falkland’ – a clergyman’s wife, who was famously scathing in her condemnation of his alterations to her texts. She was an educated intelligent woman but she didn’t have the connections or reputation that Scott had. Like Olive, she became a footnote and an amusing story to tell about how charming source behavior can sometimes be.

That being said, we don’t condemn the many fine male folk-song collectors and scholars within this field, from David Herd to Bertrand Bronson. They produced important collections during times when women weren’t expected – nor allowed the opportunities – to do other than shout the next line from the kitchen. And when we think about that, perhaps Olive Dame Campbell actually did blaze a trail by getting her name with Cecil Sharp’s on the title page of the first edition of English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians.

What’s sad for us is that her truly pioneering work, which predated Sharp by years, seems to have often been systematically sidelined. Sharp on his collecting travels throughout Appalachia was accompanied by his “secretary” Maud Karpeles, who in these more enlightened times has come to be recognized as more important than Olive Dame Campbell. Olive has faded, a ghost whose power and influence are as yet unsung. We have hope and confidence that future scholars will fill out her life and recognize her contributions to preserving and perpetuating the songs we still sing today.

Thank you to our guest bloggers Jack Beck and Wendy Welch, who wrote this blog post about Olive Dame Campbell, the perfect post to accompany our current special exhibit, on display through May 31, 2018.

Jack was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, and lived most of his life there. A founding member of Heritage, one of the seminal traditional Scottish bands of the 1970s and 1980s, he was also the musical partner of Barbara Dickson. Awarded an honorary lifetime membership in the Traditional Music and Song Association for his services to Scottish traditional music, he spent five years as external examiner in Scots Traditional song at the Royal Scottish Conservatoire in Glasgow. Jack has lived for the last twelve years in Big Stone Gap, Virginia with his wife Wendy Welch, in the heart of Appalachia and old-time mountain music. Wendy is the author of four books, the most recent Fall or Fly detailing effects of the opioid crisis on foster care. She has a PhD in Folklore, is book editor for the Journal of Appalachian Studies, and was founding director of a storytelling non-profit in Scotland. Together they run a bookstore – Tales of the Lonesome Pine – the subject of Wendy’s memoir The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap from St. Martin’s Press.