Yodeling? Maybe for Jimmie Rodgers, but not for the little-known W. E. Myer.

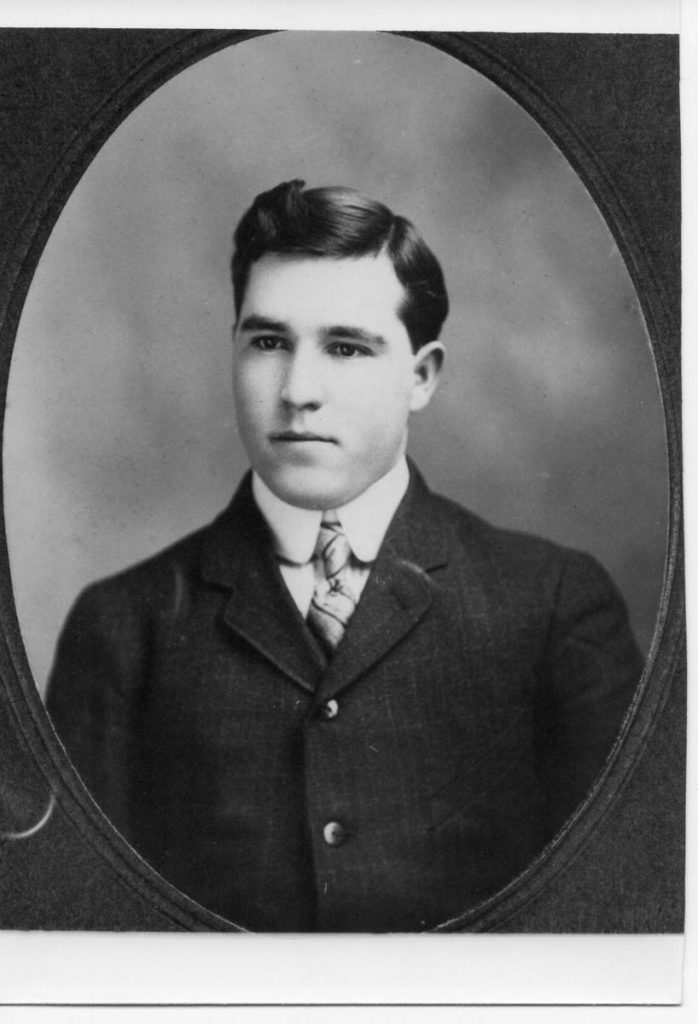

William Evert Myer (1884—1964) was an entrepreneur from Richlands, Virginia, who tried his hand at producing a successful record label called Lonesome Ace. Sadly he felt the crushing blows dealt by the Great Depression instead. A man of many interests and talents, Myer taught school, studied law, and worked on the accounts of a coal company before following his musical dream. He sold phonographs and records in his store and also wrote several songs – or “ballets” as he called them – preserving them in a set of manuscripts that were recently donated to the Birthplace of Country Music Museum’s collections.

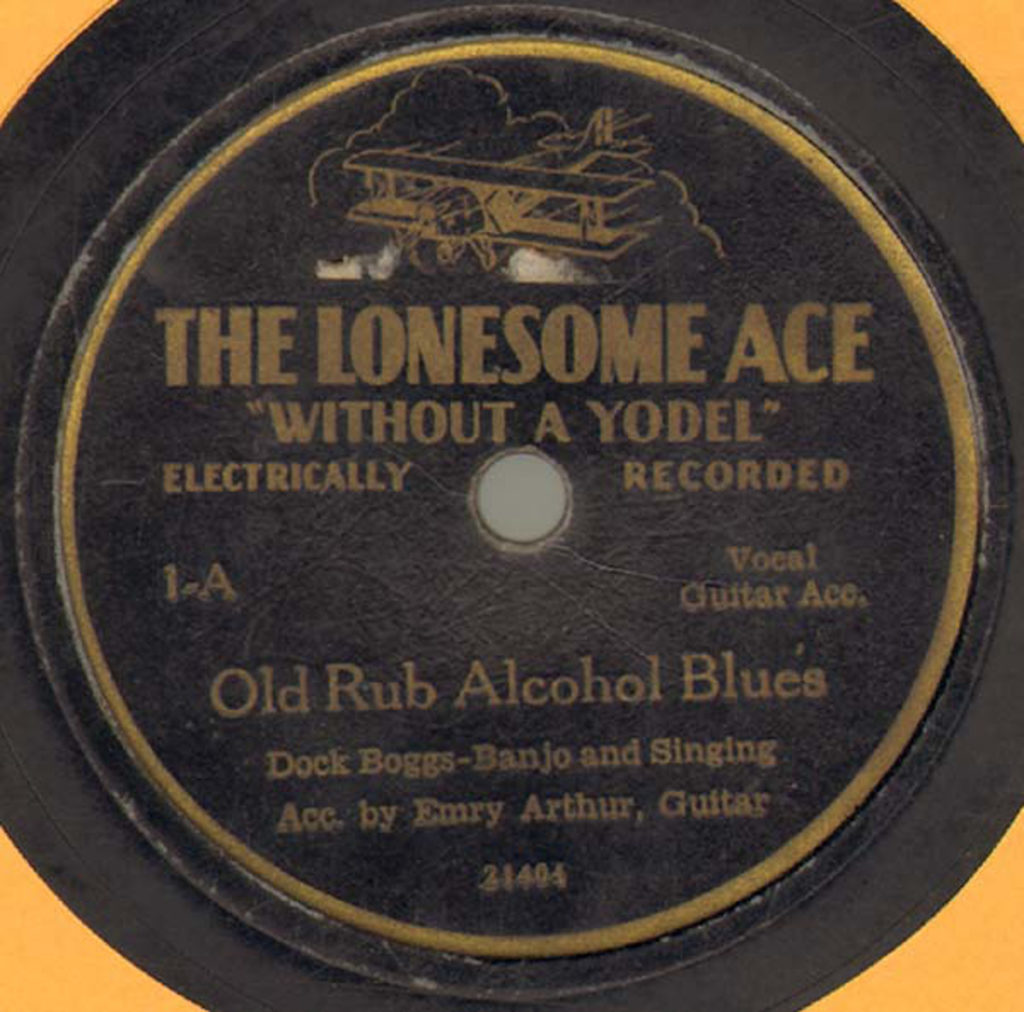

Unlike much of the rest of the listening public at this time, Myer didn’t like Jimmie Rodgers’ popular yodeling sound. Indeed, he immortalized his thoughts on this subject with his Lonesome Ace record label. Each record was blazoned with Charles Lindbergh’s plane The Spirit of St. Louis and bore the motto “WITHOUT A YODEL”! Lonesome Ace’s promotional material also declared: “Every song has a moral,…and all subjects are covered without the use of any ‘near decent’ language which is so prevalent among many of the modern records.” Myer’s quirky label and his work to release records were the culmination of all of his hopes: a removal of yodeling from the lexicon of American popular music and a desire to shares his musical loves.

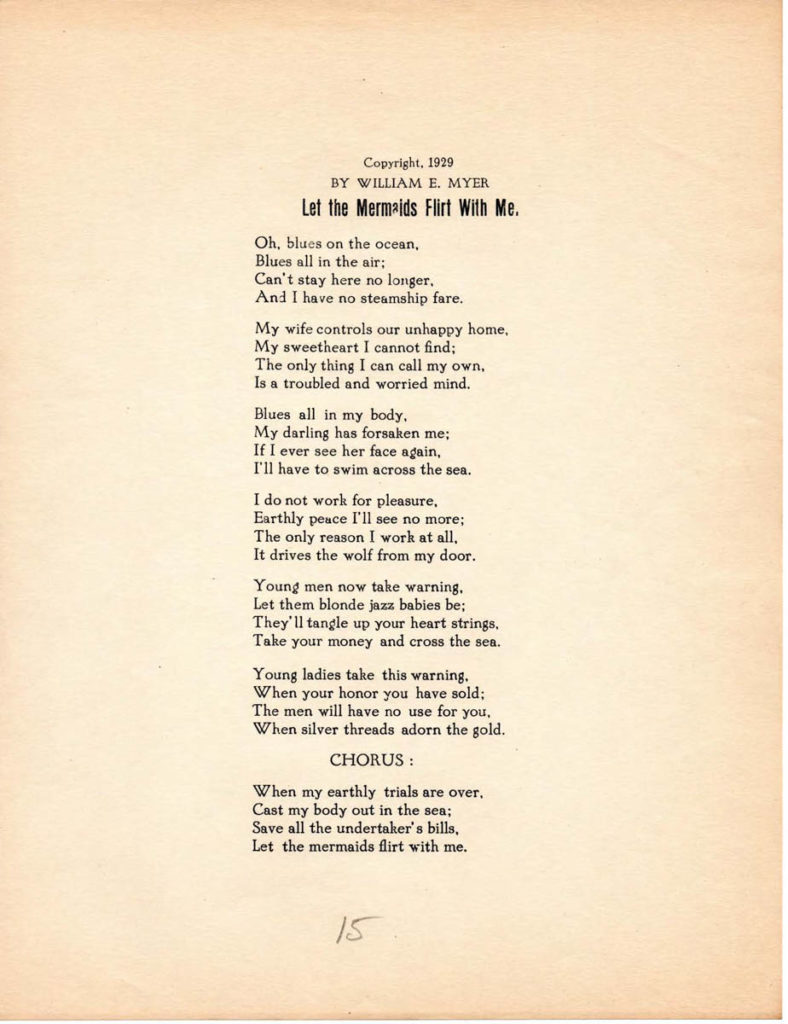

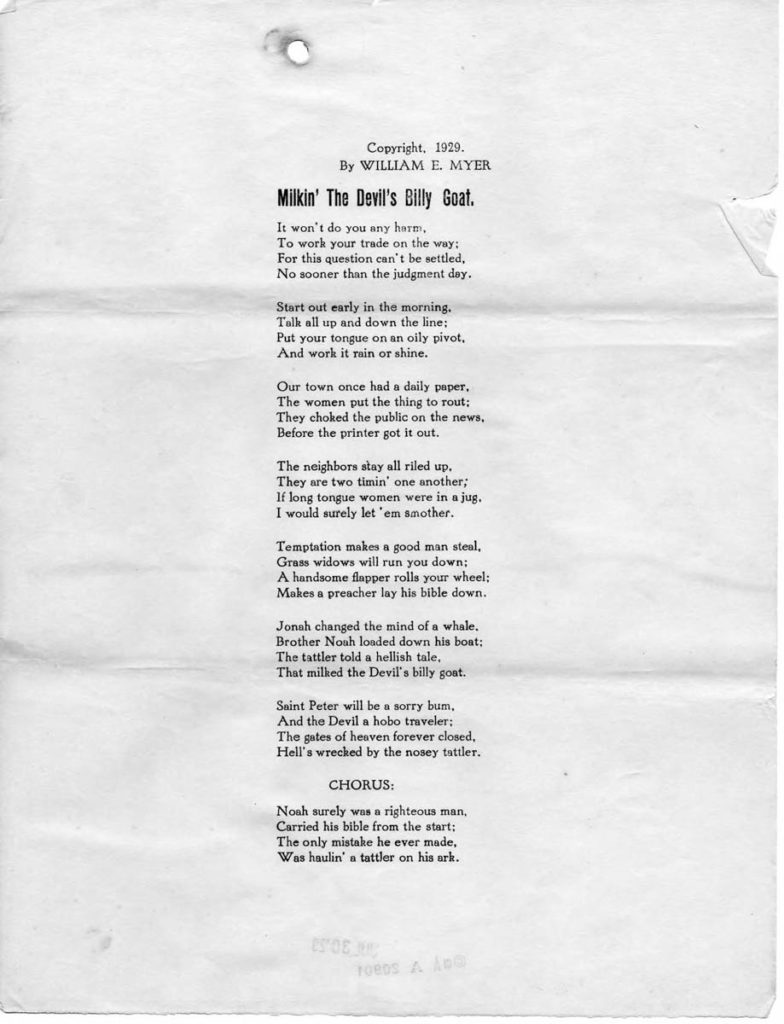

Myer’s strong opinions led him to seek out more well-known musicians as a way to market his own songs. Most of all, he wanted his songs to be performed by musicians he liked, and one of his grandest notions was to have the famed country-blues musician Mississippi John Hurt set lyrics that Myer wrote to music. He sent Hurt several of his compositions, and Hurt set three of them to music he chose: “Waiting for You” and “Richlands Woman” set to his own melodies and “Let the Mermaids Flirt with Me,” ironically set to Jimmie Rodgers’ “Waiting for a Train.” This last song was a wild mixture of country, blues, and legendary sea creatures that was later recorded by musician Tom Hoskins in 1963.

Myer also approached traditional musician Dock Boggs, a banjo-frailing, hard-drinking coal miner from a musically inclined family in West Norton, Virginia. Boggs had recorded with The Magic City Trio, led by Fiddlin’ John Dykes, with New York’s Brunswick Records in March 1927, the same year as the Bristol Sessions. During the succeeding years, he did well playing in his local community for various dances and events, much to the chagrin of his wife. And In 1929 Boggs recorded with the Lonesome Ace label, producing four sides of Myer’s “ballets” with his own choice of tune, but following Myer’s advice with “False Hearted Lover’s Blues” by setting it to Myer’s suggestion of Boggs’ “Country Blues.” Even with Boggs’ skill and Myer’s entrepreneurship, the Great Depression led to the decline of the record label and Dock’s career as a musician. Myer declared bankruptcy in 1930 after releasing only three records, and Dock pawned off his banjo to make ends meet.

However, this was not the end of Dock Boggs or of W. E. Myer’s music. During the folk revival of the 1960s, Boggs was rediscovered by folk musician and folklorist Mike Seeger, who traveled to Virginia and located Boggs at his home near Needmore. Boggs had recently purchased another banjo, and after Seeger heard him play it, he convinced Boggs to perform at various folk festivals and clubs. This rediscovery brought a renewed love by the American public for the music of Dock Boggs, which continues through today.

Myer, though not revitalized by the folk revival, continues to be known because of his association with Boggs and other important musicians. The stories told to us by his family underline what a remarkable character Myer was, and his manuscripts, which are now part of the museum’s collection, highlight this even further. With song titles like “Old Rub Alcohol Blues” and “Milkin’ the Devil’s Billy Goat” – and one of my personal favorites “The New Deal Won’t Go Down,” which supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program – it is clear that Myer’s songs reflected a wide range of interests and stories! And while Myer’s Lonesome Ace may not be well-known or prolific, it certainly played a noteworthy role in the folk music of Southern Appalachia – even “without the yodel”!

Along with the William E. Myer manuscripts, the donors generously gave the museum several other items related to their great-grandfather, including the collector’s edition of The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records Vol. 2 (1928-32), which contains the duets by Emry Arthur and Della Hatfield of the two Myer’s songs they recorded.