Ellie Davis is an intern at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum and a student at East Tennessee State University where she studies Human Studies with a minor in Old Time Music Studies.

As an avid old-time and folk musician, I thought I’d share some interesting background behind one of my lifelong inspirations, Emmylou Harris, and more specifically, the story behind her guitars. As a young girl, I was always so drawn to Emmylou because of her beautiful voice, her unapologetic stage presence, and her big, powerful guitar.

For those who might need an introduction or refresher on Emmylou Harris, she is a fourteen-time Grammy Award winner and Country Music Hall of Fame inductee, and has been a pioneering women musician in country and folk music for decades. Emmylou’s career was transformed when she was discovered by country music legend Gram Parsons in the early 1970s, and when he invited her to join his band, their duet harmony singing immediately captivated listeners. Another one of Emmylou’s most memorable collaborations was with Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt, where their iconic 1987 album, “Trio”, featured unforgettable harmonies that remain a landmark in country music history.

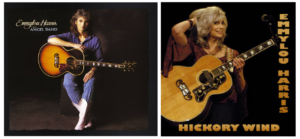

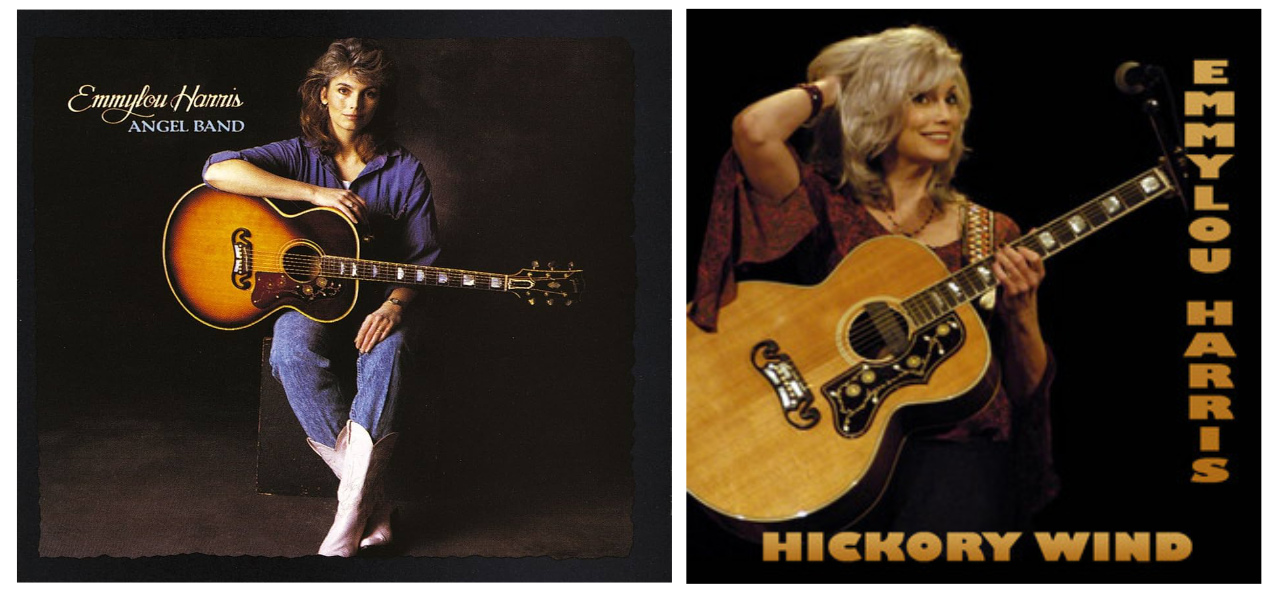

Now, let’s get back to Emmylou’s guitar. Because the music industry has notoriously been unwelcoming to women musicians, it’s too often generally accepted that women should not take up as much space, or be heard as loudly as their male counterparts. This is one of the reasons women rarely performed solo for many years and you still don’t often see women performing with big guitars. Like a lot of country artists, Emmylou found her signature guitar early on, and it remained her staple instrument for decades. This guitar for Emmylou was the. With the S and J standing for “Super Jumbo” this guitar is large bodied, with a rosewood neck, maple sides and back, mother-of-pearl inlay, and has strong bracing inside the body of the guitar. For non-guitar nerds, bracing refers to a guitar’s internal support system; essentially the bones of the guitar. It’s made of thin pieces of wood that are glued to the inside of the guitar’s top, and they help to both strengthen the instrument and control the vibrations of the strings, making the sound better and stronger. Gibson calls this guitar the “King of the Flat Tops” due to its popularity with American artists, but you almost never see a woman playing one. You can see Emmylou’s SJ-200 pictured on her 2001 album, Hickory Wind and a darker stained version of the same model on the cover of her 1987 album Angel Band.

Because Emmylou made this guitar model so famous, Gibson even created a limited edition custom model dedicated to her, called the Gibson L-200. It’s a slightly smaller and lighter weight model of the exact same guitar with the exact same bracing inside it, making it more accommodating to smaller musicians while still preserving the full and striking sound. Emmylou now performs most often with the L-200. Gibson introducing a new custom model in honor of Emmylou shows how she has led by example and carved out space in the music industry for other women musicians to rise up and feel more of a sense of belonging.

Just like Gibson did with their custom, guitar, I hope to honor Emmylou’s unique musicianship with this ode to her instrument and how she likes to be heard. Emmylou is admired because of the duality in her musicianship. She can sing so tenderly and allow her femininity to be so prominent, and at the same time, she takes up space with her big guitar and her strong voice. The harmonious balance she strikes between vulnerability and strength paves the way for so many women musicians following in her footsteps.

![The cover of the original "Sacred Harp" hymn book. It is old and worn, reading "The Sacred Harp, a Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes, Odes, and Anthems; selected from the most eminent authors, together with nearly one hundred pieces never before published. Suited to most metres, and well adapted to Churches of every denomination, singing schools, and Private [word obscured]. With Plain Rules for Learners. By B.F. White and E.J. King](https://birthplaceofcountrymusic.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/image11-300x199.jpg)