Today is #MuseumSelfie Day, a chance for museums across the globe to show the fun side of museums – and it’s not just for museum people! You can join in the fun by sharing your own selfie in our museum, or others!

Our BCM staff are pretty passionate about the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, and they’ve stepped up on #MuseumSelfie Day before. This year I asked them to take a selfie in front of a panel, photograph or object in the museum’s exhibits that shared some surprising or particularly interesting information. Check out their picks below – and then come out to the museum, take your own selfie, and share it on social media with the tags #MuseumSelfie and #BCMMuseum.

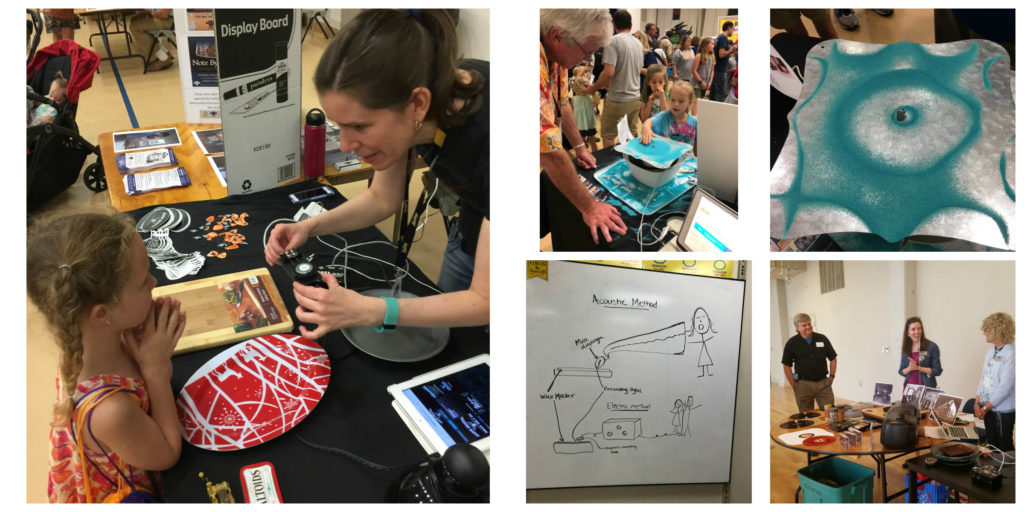

Summer Apostol, Toni Doman, Kris Truelsen (Producer), Josh Littleton (Engineer & Technical Administrator), and Lawrence Inscho

You might have listened to our in-house radio station, Radio Bristol, but if you haven’t visited the museum yet, you might not know that not only is it a live, working radio station but it is also an integral part of our museum exhibits. Visitors can regularly see our DJs at work and be part of the audience for some of their live performance shows. Guests like Lawrence Inscho, a regular on On the Sunny Side, always bring a new and interesting perspective to our radio listeners, and Kris, Josh, and other members of the Radio Bristol team share their enthusiasm for their work every day! As Toni notes, it’s wonderful to see so many talented artists and guests visit the station and be continuously inspired by the museum, and hosting her own radio program, Mountain Song & Story, is also a blast especially when Summer stops in to help her out with sound effects for the show!

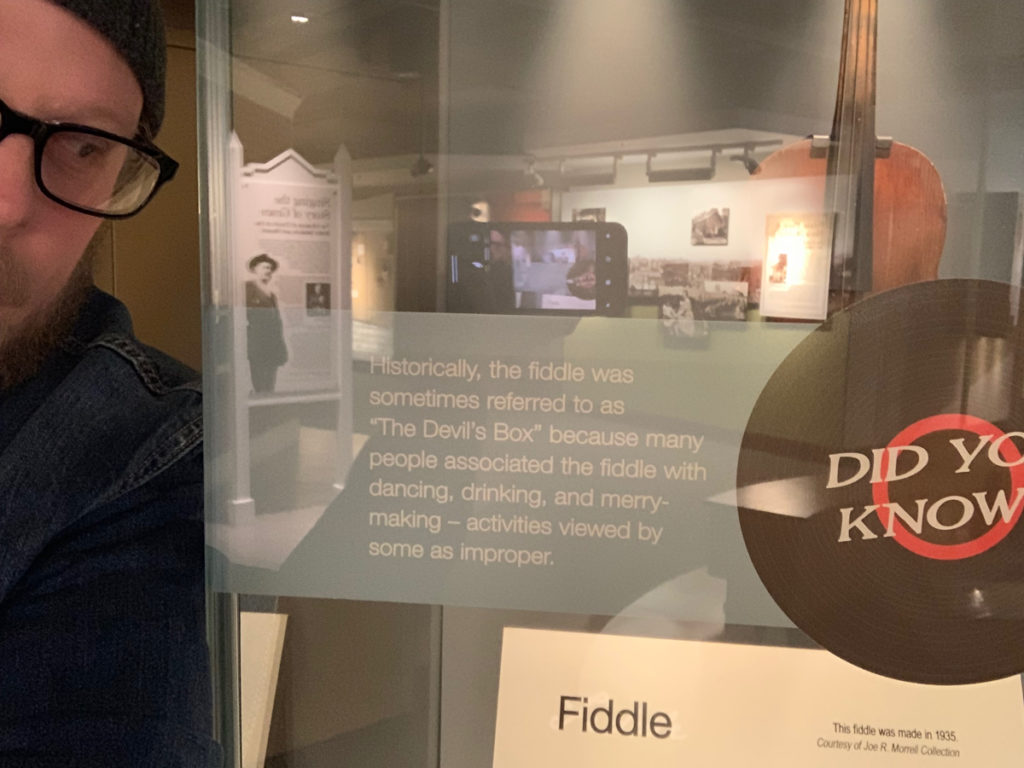

Scotty Almany, Digital Resources Manager & Catalog Associate

Did you know that the fiddle has also been called “the devil’s box”? This is my favorite piece of information in the museum. It has been used to stump many who have wagered that they knew the answer, be they docent, visitor or co-staff member. Diabolical knowledge!

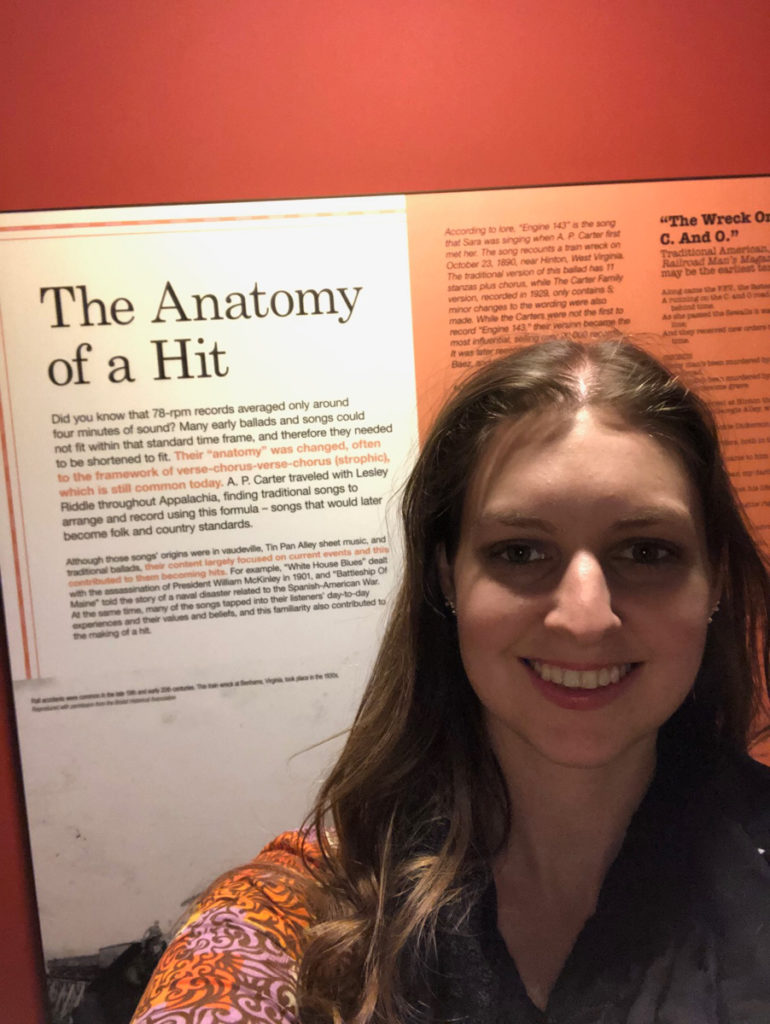

Erika Barker, Sales & Business Development Manager

The Anatomy of a Hit panel talks about how 78rpm records could only play about four minutes of sound on average. Most early songs and ballads are much longer than that, and therefore they had to be rewritten and shortened to fit on the records accordingly. I had known since I was young that most songs on my old CDs and on the radio even today are about 3-4 minutes long, but I never knew why that length had been chosen as the music standard until reading this panel. Just goes to show how much early record recording techniques and equipment still influence the music industry today!

Rene Rodgers, Head Curator

There are so many wonderful objects in the museum, and I particularly love the early music playback machines from large phonographs within cabinets as can be seen here to phonographs with visible morning glory horns to portable cylinder players. What’s interesting to me is that these machines, along with the cylinders and records played on them, were usually sold in furniture stores, rather than dedicated music stores. Phonograph needles are also slightly surprising in that they were only good for a certain number of “plays” – so you had to keep buying them!

Summer Apostol, Frontline Associate

As a history major, and general lover of history, I think it’s critical to connect the past to the present – to show people that history is relevant and important! The museum does a beautiful job of showing its visitors that the 1927 Bristol Sessions are, in fact, very important and relevant. One way this feat is achieved is with the kiosks that let you listen to covers more modern musicians (like Nirvana) have arranged. One of the coolest spots in the museum, in my opinion!

Emily Robinson, Collections Manager

I’ve always associated old-time music with banjos and fiddles, so when you visit the museum and see the wide range of instruments that are part of that music, such as kazoos and ukuleles, it comes as a bit of a surprise. I was particularly interested to see that Alfred Karnes (possibly) played a harp guitar at the Bristol Sessions!

Toni Doman, Frontline Associate

Any time I get the chance to dance, I’ll take it! Here I am swinging with Pokey LaFarge in the museum’s Immersion Theater. Several of the images in the museum have been taken at Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion, and it’s great when people come to visit and then get to see themselves as part of the museum’s exhibits. A wonderful surprise!

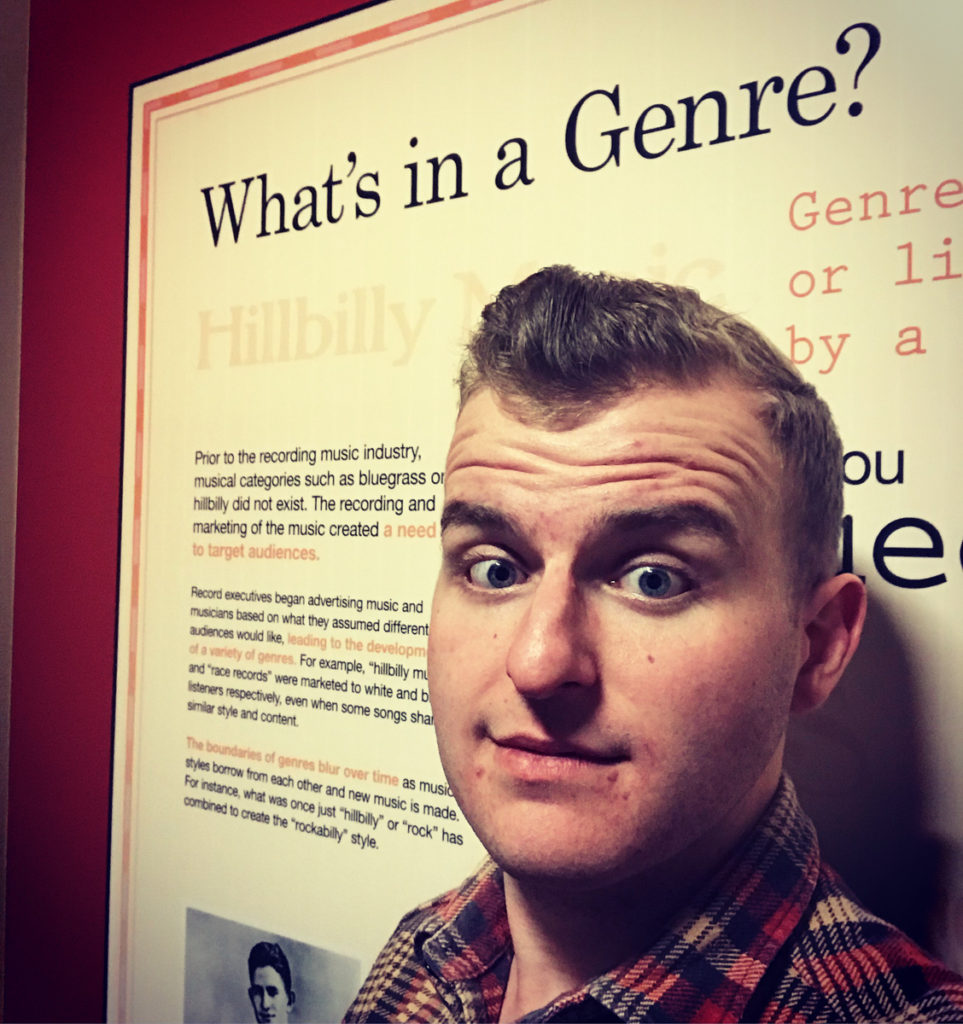

Nathan Sykes, Production Assistant

One of my favorite ideas that is explored in the museum is the idea that genre is a concept that was made up to sell records. Before the record industry put terms such as “Hillbilly” and “Race” on the music, it flowed freely and transcended culture, and musicians played whatever music was called for. From breakdowns to blues to ballads, musicians adjusted their set lists to fit the occasion. To put it simply, good music is good music, and everything from polka to hip hop to bluegrass has value. When we set aside our preconceived notions of genre, our ears and minds are opened to new ideas and experiences we couldn’t imagine if we only think of music along strict genre lines.