“Country music”, along with its variations, is not often a term you’d associate with academia, at least not until you have a good understanding of the vast field of musicology. As a historian of music, I often find myself at the crossroads trying to explain what I study and how I study it. My succinct answer is, a historian of music studies music, but not strictly musicologically, but rather uses music to scrutinize history. This, in my opinion, is disparate from music historians, or musicologists with an emphasis on history, for whom the product of music itself is the central subject. As for country music historians, country music as an art form comes first and foremost, but that doesn’t mean it’s just about the music. As a genre with humble roots, one can’t talk about country and folk music without referring to historical and sometimes political contexts.

Today, country music is a recognized, albeit small, academic discipline with international appeal. One of American folk music’s early advocates, Charles Seeger (1886-1979) helped spearhead the founding of the Society of Ethnomusicology (SEM). Seeger envisioned for music to be communicated and studied musically, instead of merely through linguistics as crutch. He advocated the role of the (ethno)musicologist to be a transmitter of music but also critic of culture. The field today has mostly evolved a long way from the days of Seeger. Musicology nevertheless still relies heavily on textual analyses of music, which, tellingly, did not necessarily become a point of concern for professionals. Currently, country music in academia is taught primarily as a form of performing arts, and less as a theory or history. The International Country Music Conference (ICMC), founded in 1983, has been held annually at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee since 1998. This year it runs from May 30th to June 1st.

For those who aspire to become professional musicians or work in the country music industry and adjacent, East Tennessee State University, Morehead State University, and Denison University offer degree programs in the genre. Other institutions in North America including the Berklee College of Music, USC Thornton School of Music, University of Miami, University of Saskatchewan MacEwan University offer, or have offered in the past, courses and an initiative on country music. The Country Music Foundation based in Nashville had published the Journal of Country Music from 1971 to 2007. The journals are archived and still accessible through many higher institutions, as well as the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum digital archive.

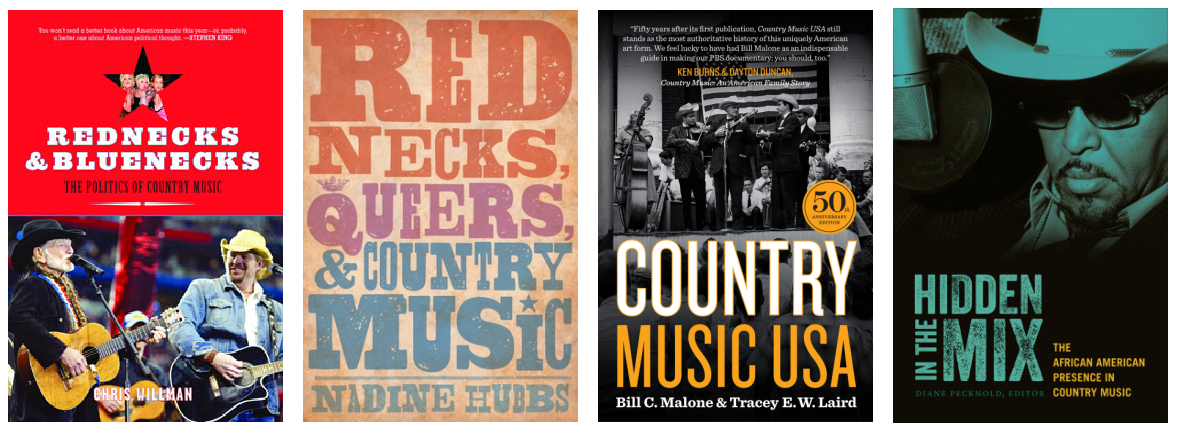

If you are interested in reading academic writings on country music, a good place to start is with anything by historian Bill C. Malone, professor of history emeritus at Tulane University. Country Music U.S.A. (1968) is inarguably the first academic history book on country music. The turn of the twentieth century saw the political bifurcation within country music, shown through monographs such as Charles K. Wolfe’s Country Music goes to War (2005) and Rednecks and Bluenecks: The Politics of Country Music (2007) by journalist Chris Willman. In recent years, academics have leaned more toward socio-political themes, displayed in work like Diane Pecknold’s Hidden in the Mix: the African American Presence in Country Music (2013), Nadine Hubbs’ Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music (2014), Peter La Chapelle’s I’d Fight the World: A Political History of Old-Time, Hillbilly, and Country Music (2019), and anthology Whose Country Music? Genre, Identity, and Belonging in Twenty-First-Century Country Music Culture(2022).

Just like the grassroots of country music itself, the academia of country music also reflects the debates that are present in the country music scene. The problem of “authenticity” has plagued various art forms and genres, but with a genre like country music, it is particularly prominent. Recently, philosophy professor Evan Malone published an excellent piece on the topic in the British Journal of Aesthetics in a 2023 issue. With references to a range of scholars with backgrounds from Anthropology to Aesthetics with an emphasis on country music, including Jack Bernhardt, John Dyck, Richard Shusterman, it demonstrates the versatile ways country music can be studied academically.

In my very own first year of PhD for a final’s assignment, I assembled a lecture in history on medieval Celtic and African musical traditions and their manifestations in Appalachian folk music—a connection that often surprises non-listeners. Outside of traditional academia, current events surrounding and within country music have been covered by journalists and critics, such as Emily Nussbaum’s 2023 piece for The New Yorker.

Alas, it is challenging to include a more thorough academic country music discography here. In an effort to keep this blog digestible, I am only able to give you taste of the available literature and must leave many scholars out of this post. I encourage you to start your own reading journey and dive into the academic world of country music with me. As country music enters a new phase both artistically and in popularity, we can certainly anticipate further exciting discussions in the near future!

Guest Blogger Emily Lu is a PhD candidate in History at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida.