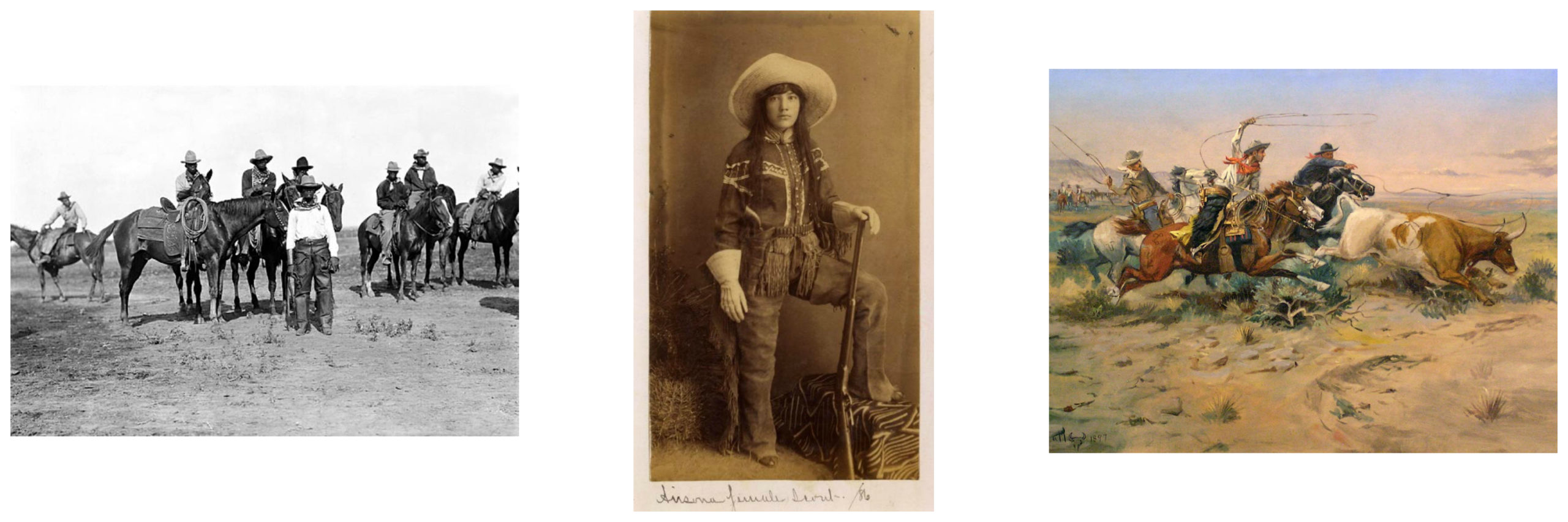

Today is the National Day of the Cowboy, marked in several states on the fourth Saturday of July every year. Country music, in the past and the present, is filled with the images of cowboys and cowgirls, and so we thought we’d mark today with our own celebration of cowboys with a music twist!C

Cowboy songs are said to have originated as a way to soothe nervous and apt-to-stampede cows on cattle drives out west. The yodels and soft crooning sounds in the songs would help to obscure the noises of the night that tended to spook the herd and also act as a kind of lullaby. The songs themselves often reflected a wide range of music, including old ballads, popular Tin Pan Alley tunes, Mexican songs, and blues forms. John A. Lomax published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads in 1911, detailing 112 songs that he gathered through requests in newspapers and academic venues and by visiting known cowboy haunts. The first edition had a handwritten foreword by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Google cowboy songs today, and you can find numerous “best cowboy songs” lists, each with the individual author’s subjective preferences – from the well-known, and copyright challenged,“Home on the Range” to The Highwaymen’s “The Last Cowboy Song” to “Good Ride Cowboy,” Garth Brooks’ tribute to rodeo rider and sing Chris LeDoux. My personal favorite has always been “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” a love that began with the Alvin and The Chipmunks version of 1981 when I was a kid and thankfully later evolved to the much-better version by Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings!

In line with cowboy music, there have been numerous musical cowboys on radio, records, and screen throughout the years. Gene Autry, “The Singing Cowboy,” did it all: singing, writing songs, acting, rodeo riding. He even owned a Major League baseball team in California for over 30 years. Autry has five stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, recorded over 600 songs – many of which were also written or co-written by him, starred in 93 films, and hosted his own television show. He is most well-known for “Back in the Saddle Again,” but his biggest hit wasn’t about the American West or cowboys at all – instead it was the Christmas classic, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

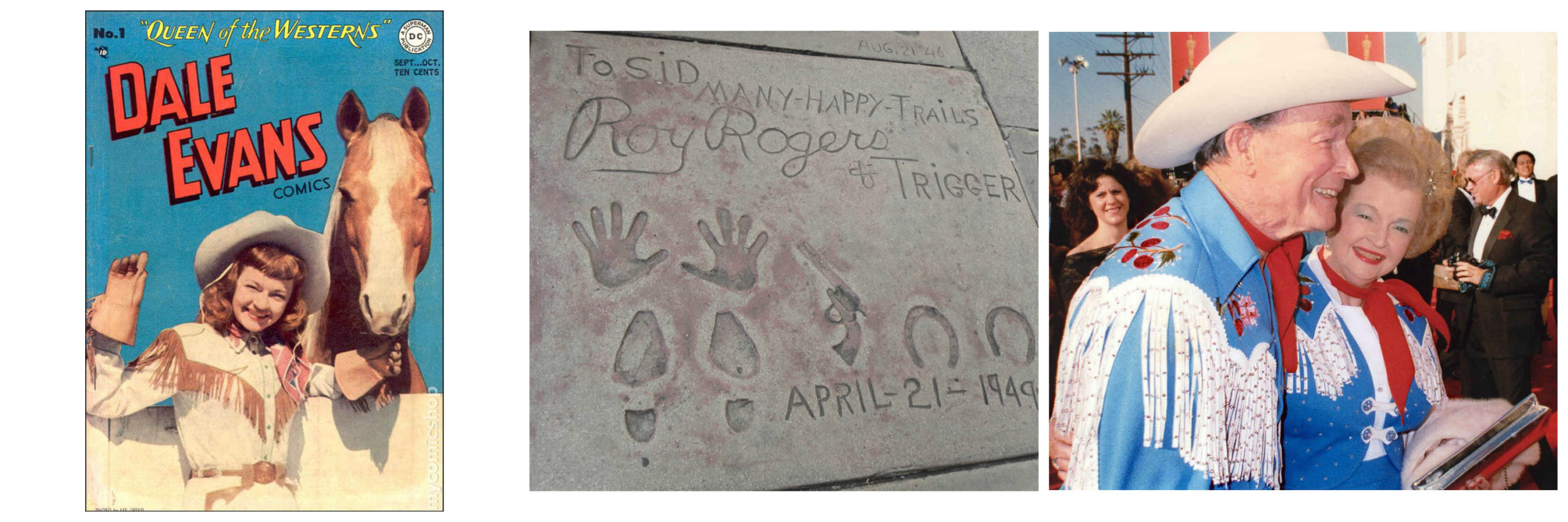

Roy Rogers and Dale Evans epitomize the musical cowboy and cowgirl. As a husband-and-wife team, they recorded songs and acted together; Evans was also a prolific songwriter. The song that is most associated with them is “Happy Trails.” Rogers, known as “The King of the Cowboys,” also brought his palomino Trigger and dog Bullet into many of his films and television shows. An exhibit on Evans at the National Cowgirl Museum & Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas, shares this quote from her, the perfect tribute to the cowgirl’s strength and independence:

“‘Cowgirl’ is an attitude really. A pioneer spirit, a special American brand of courage. The cowgirl faces life head-on, lives by her own lights, and makes no excuses. Cowgirls take stands; they speak up. They defend things they hold dear.”

Center: Roy Rogers’ and Trigger’s “signatures” at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Photograph by NativeForeigner on Wikimedia Commons

Right: Roy Rogers and Dale Evans at the 61st Academy Awards. Photograph by Alan Light on Wikimedia Commons

Patsy Montana, born Ruby Rose Blevins, was another singing cowgirl. While visiting the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933, Montana auditioned for a crooner role but ended up working with the Prairie Ramblers on WLS’s National Barn Dance, where she performed for around 20 years. She was the first female country music performer to have a million-selling record with “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart,” which was released in 1935. Her influence can be seen in later singers such as Patsy Cline and Devon Dawson, who provided the singing voice of Jessie the Yodeling Cowgirl from Toy Story.

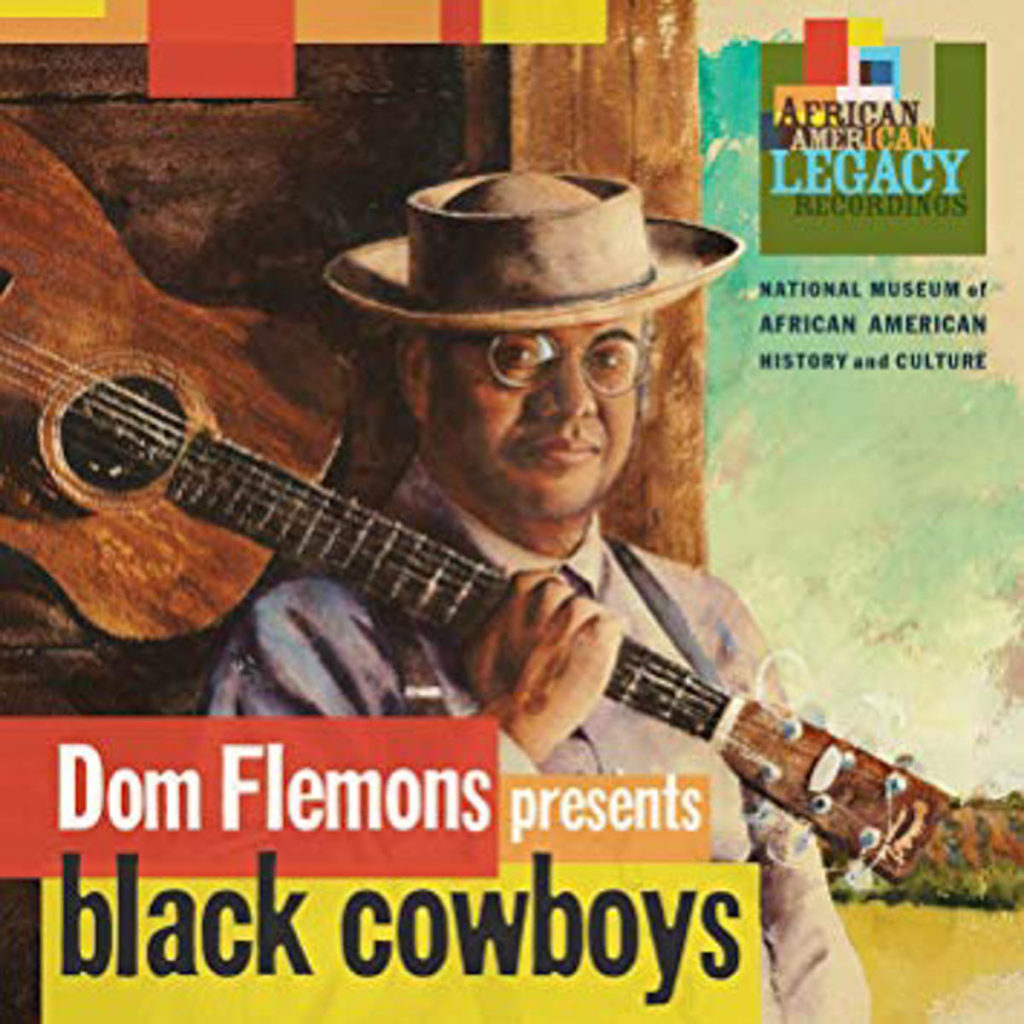

Dom Flemons Smithsonian Folkways album Black Cowboys, released in 2018, explores the history, music, and culture of the American Wild West from the perspective of the thousands of African American cowboys who also rode the ranges and pioneered the trails out west. Flemons’ album, and the research he did into the subject, underlines that cowboys weren’t exclusively white, despite popular imagery. One interesting character noted by Flemons is Bass Reeves, who became the first black deputy U.S. Marshall out west but also may have been the inspiration for the character of the Lone Ranger! Songs on the album include the familiar “Home on the Range,” “Goodbye Old Paint,” which was credited to a former slave and later cowboy, and an original song by Flemons that honors black movie cowboy Bill Hickett.

This is just a small selection of music-related stories about cowboys and cowgirls, but hopefully it gives you a taste to listen and learn more – and to start celebrating every year on National Day of the Cowboy!