On March 6, the museum opened a special exhibit called Real Folk: Passing on Trades & Traditions Through the Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Program. Two weeks later the museum closed its doors in accordance with the state mandate in response to the COVID-19 situation. Sadly that has meant we haven’t been able to share this wonderful exhibit with very many on-the-spot visitors, but happily we are able to share some of it with our virtual visitors! The curatorial team is hard at work on pulling together a virtual tour of Real Folk (so watch this space!), but in the meantime, we wanted to give you the chance to learn a little bit about the exhibit and the apprenticeship program right now.

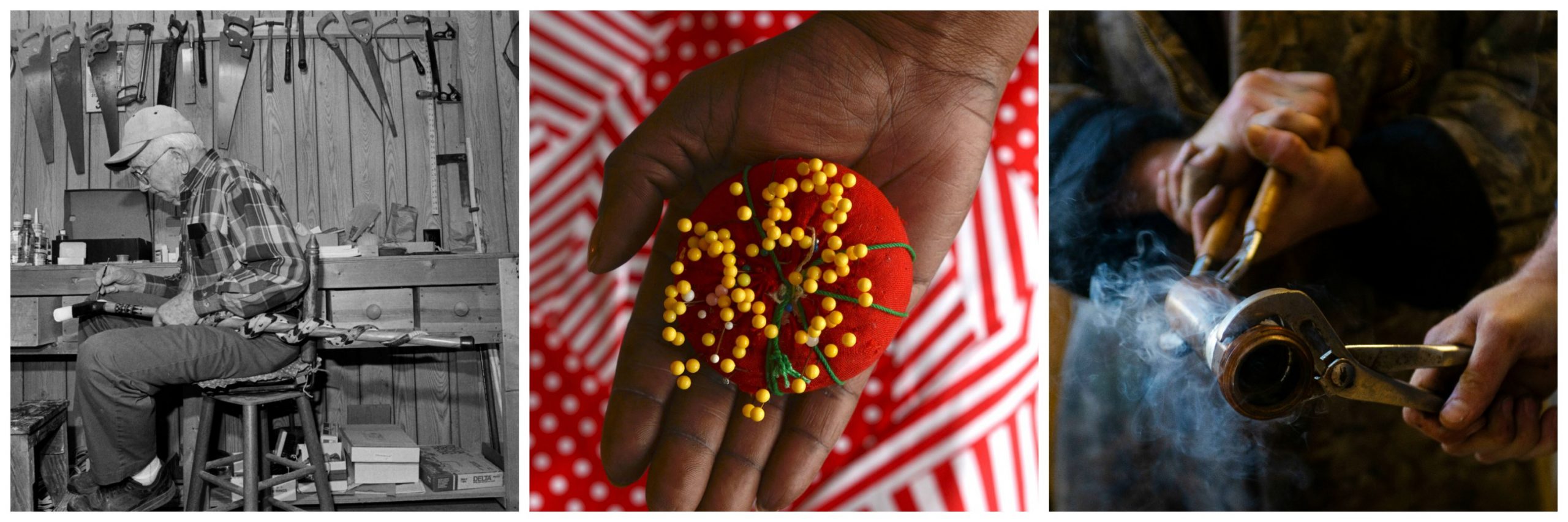

Since 2002, the Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Program has drawn from a wide range of communities and traditional folkways to pair more than 150 experienced master artists with dedicated apprentices for one-on-one, nine-month learning experiences, in order to help ensure that particular art forms are passed on in ways that are conscious of history and faithful to tradition. The master artists are selected from applicants in all forms of traditional, expressive culture in Virginia – from decoy carving to fiddle making, from boat building to quilt making, from country ham curing to old-time banjo playing, from African American gospel singing to Mexican folk dancing. These crafts and traditions come from the Appalachian hills to the Chesapeake shore to new immigrant traditions brought to the state – and everywhere in between! The Folklife Apprenticeship Program helps to ensure that Virginia’s treasured folkways continue to receive new life and vibrancy, engage new learners, and reinvigorate master practitioners.

Out of these apprenticeship pairings, deep friendships and relationships have grown as the master artists pass on their knowledge, skills, and passion for the various crafts and traditions, along with the history and cultural importance that attaches to each. For instance, Sharon Tindall, who worked with gifted quilter Nancy Chilton in 2014, specializes in early African American quilt patters and in working with fabrics that aren’t typically used in quilting, such as Malian mud cloth. She is also a quilt historian and has conducted substantial research in support of the theory that African American quilts contained coded messages that were integral to the success of the Underground Railroad.

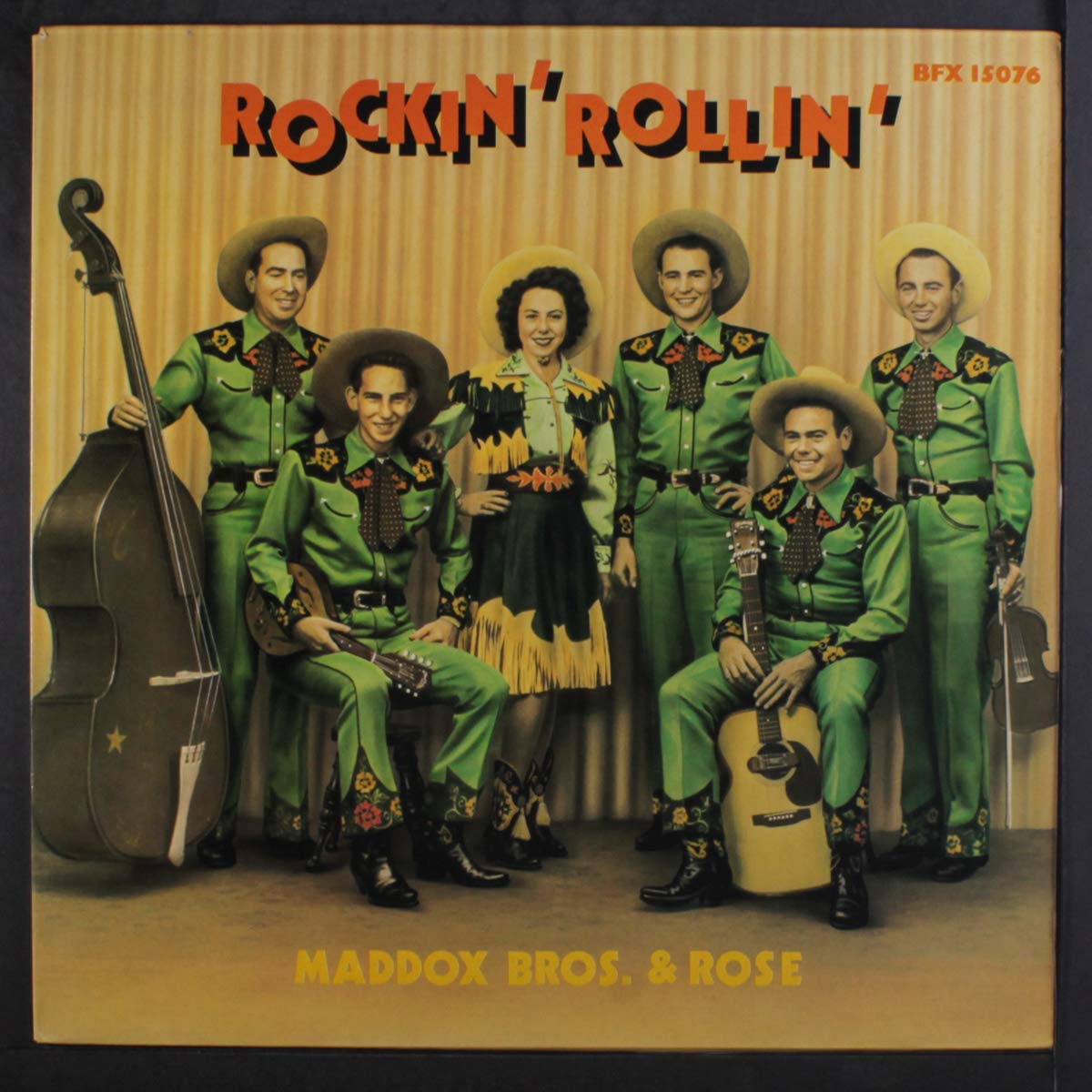

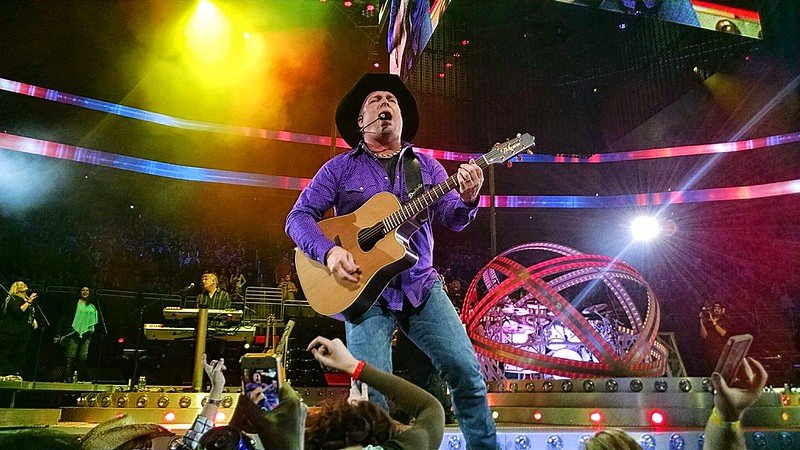

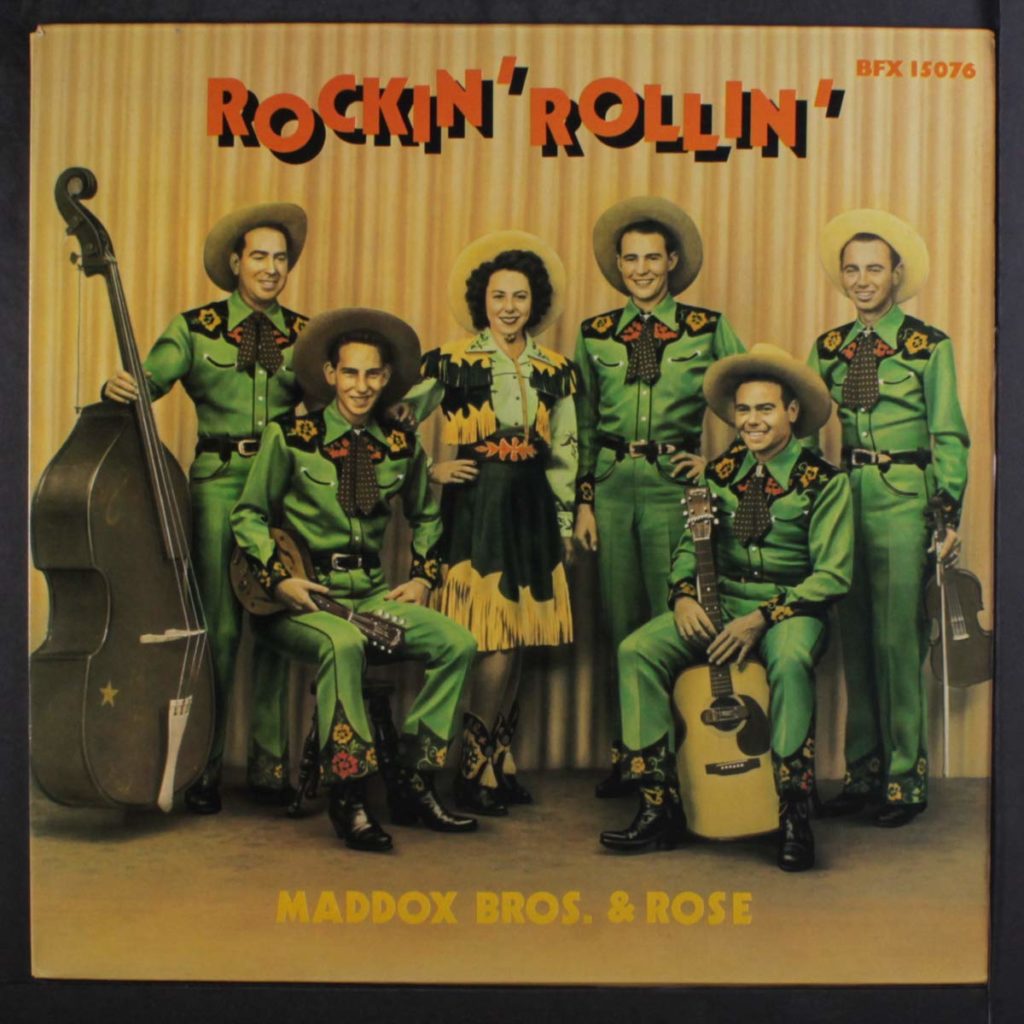

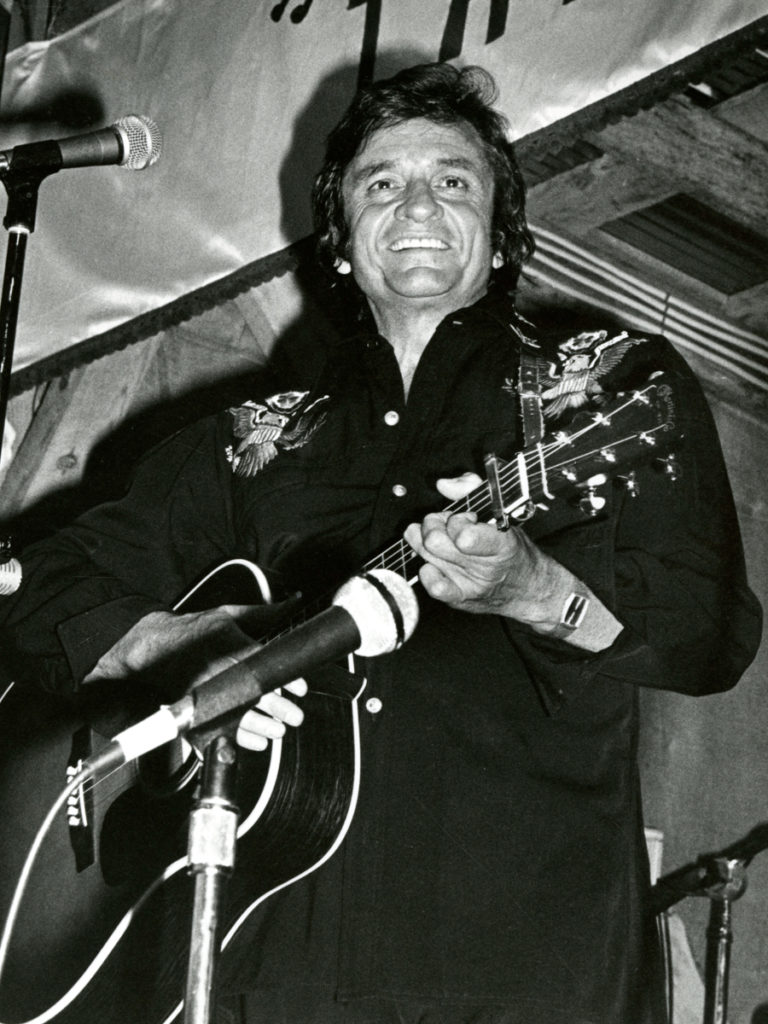

Several apprenticeships have focused on music, from music making to instrument building to the related art of dance. The variety of traditions on display within this realm is astounding, including African American gospel, Chickahominy dance, bluegrass fiddling, mandolin making, Sephardic ballad singing, steel drum making, and so much more. Because music is so central to the cultural heritage of southwest Virginia, numerous musicians, singers, and makers from this area have taken part in the program. Musician and luthier Gerald Anderson spent more than 30 years apprenticing in the shop of legendary instrument builder Wayne Henderson in Rugby, Virginia. Fellow musician Spencer Strickland recognized his mastery and skills, and asked if Gerald would take him on as an apprentice. Their time working together in 2005 turned into a deep friendship, musical partnership, and one of the longest running and most successful apprenticeships in the program’s history. Though barely out of his teens at the time, Spencer took to building instruments immediately, and the two soon opened their own shop in Gerald’s home in Troutdale. They also played and toured together as a duo and with the Virginia Luthiers. Gerald passed away unexpectedly in 2019, and Spencer has continued to build instruments and carry on Gerald’s memory.

Many of Virginia’s cultural traditions have been brought here by immigrant communities, and the state is all the richer from this. These immigrants have shared their heritage not only within their own communities, but also more widely through educational programs, touring and performances, the creation of larger cultural organizations, and partnerships with other groups. For instance, Nam Phuon Nguyen began playing the đàn bâu at 17, later touring throughout the United States with her family as the Nguyen Đinh Nghĩa Family and performing at prestigious concert halls and festivals. The đàn bâu – translated to mean “gourd lute” – is a monochord (one-stringed) instrument, which plays a central role in Vietnamese music. Guitarist Anh Dien Ky Nguyen met Nam Phuong while playing at a music club, and he asked her to teach him the đàn bâu, partnering with her in the apprenticeship program in 2011.

These few images are just a taste of this fascinating and beautiful exhibit, and we hope that you will be able to visit it later in the year. In the meantime, you can engage with the exhibit in another way by listening in to Radio Bristol’s Toni Doman as she talks with Virginia Folklife photographer Pat Jarrett about his work with the apprenticeship program — check out Episode 60 on March 12, 2020 in the Mountain Song & Story archives here. And you can support the artists who are so important to Virginia’s cultural heritage by going to Virginia Folklife’s website and exploring TRAIN (Teachers of Remote Arts Instruction Network). Created in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic and its devastating impact on the livelihoods of artists, TRAIN connects interested students of all skill levels with a diverse range of master musicians, craftspeople, and tradition bearers offering online instructional opportunities. Start your lessons today!

Finally, keep an eye on our website for a virtual tour of Real Folk coming soon!