January 15th is recognized as Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In recognition of Dr. King’s important work and fight for the equal rights of black Americans during the Civil Rights movement, this blog details the music of the movement. Originally posted on December 29, 2018 and written by Rene Rodgers.

Here at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, we’ve spent the past month and a half exploring the power and impact of visual imagery through the NEH on the Road exhibit For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights (on display until January 7, 2019). But we’re a music museum, and one thing we know for sure: music has power and impact too.

And that is certainly true when you think about the music of the Civil Rights movement. Many of these songs had their origins in traditional hymns and African American spirituals, and while they weren’t all originally about freedom and social justice, their message was clearly relevant. Some were also revised to include new lyrics that spoke directly to the issues people were facing, such as voting rights. Others grew out of the musicians’ personal experiences or observations of the discrimination around them. These songs – often and rightfully called anthems – inspired determination and bravery, helped to lessen fears and steady nerves, focused activists’ passion and energy on the task at hand, and acted as motivators to protesters and observers alike. They were delivered by professional musicians and groups like the Freedom Singers, but more importantly they became the unified voice of ordinary people displaying extraordinary courage at rallies, marches, and protests and in churches, meetings, and workshops.

There are many accounts of this music history and the songs of the Civil Rights struggle in books, audio collections, and films such as Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song, We Shall Overcome: A Song That Changed the World, Let Freedom Sing: The Music of the Civil Rights Movement, Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs, Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: Black American Freedom Songs, 1960-1966, Freedom Song: Young Voices and the Struggle for Civil Rights, and Soundtrack for a Revolution (screened at the museum in November). All of these are worth exploring to get a better understanding of the place and significance of music in the fight for civil rights over the years.

A blog post about this music would be incredibly long – it’s a long and interesting history and each song has a story! And so, we’ve chosen just five songs that highlight the power of this music, including a brief history or description of each, to get you started on an incredibly inspiring musical journey.

“Uncle Sam Says,” Josh White (1941)

Josh White’s 1941 record Southern Exposure: An Album of Jim Crow Blues, co-written with poet Waring Cuney, was called “the fighting blues” by author Richard Wright, who wrote its liner notes. One of its songs, “Uncle Sam Says,” highlighted the frustration felt by African Americans when faced with the continuing effects of Jim Crow even as they fought and gave their lives for their country. It was inspired by White’s visit to his brother at Fort Dix in New Jersey where he saw the segregated barracks and unequal treatment of the black servicemen. After the album was released, White was invited by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the White House for a command performance, the first black artist to do so.

“This Little Light of Mine,” Rutha Mae Harris

For many of us, “This Little Light of Mine” is a song of our childhood sung at school or church. But the song has a much more interesting history within the Civil Rights movement and beyond as a “timeless tool of resistance” – check out this NPR piece from August 2018 that celebrated the song as a true “American Anthem.” The song, both a spiritual popular in the black churches and a folk song, became even more impactful when it was employed by Civil Rights protesters and activists who often personalized the lyrics to the situation or as a way to name the oppressors they were facing. Original Freedom Singer Rutha Mae Harris demonstrates the energy and power of the song as she leads a contemporary group in its verses at the Albany Civil Rights Institute:

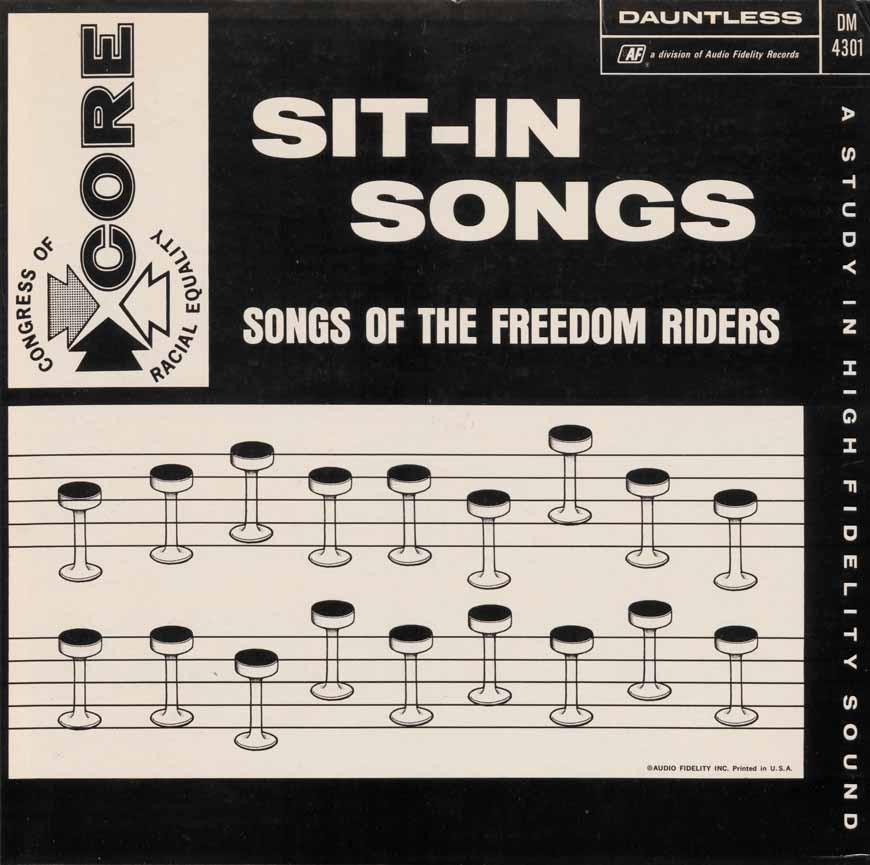

“I Shall Not Be Moved,” The Harmonizing Four (1959)

This African American spiritual is based on Jeremiah 17:8—9, reflecting the idea that the singers’ faith in God will keep them strong and steadfast. The song became a popular resistance anthem during the Civil Rights movement, especially in relation to sit-ins; it was also used as a labor union protest song. As with “This Little Light of Mine,” the lyrics were sometimes altered to speak to the specific cause. Maya Angelou’s poetry collection I Shall Not Be Moved was named after the song.

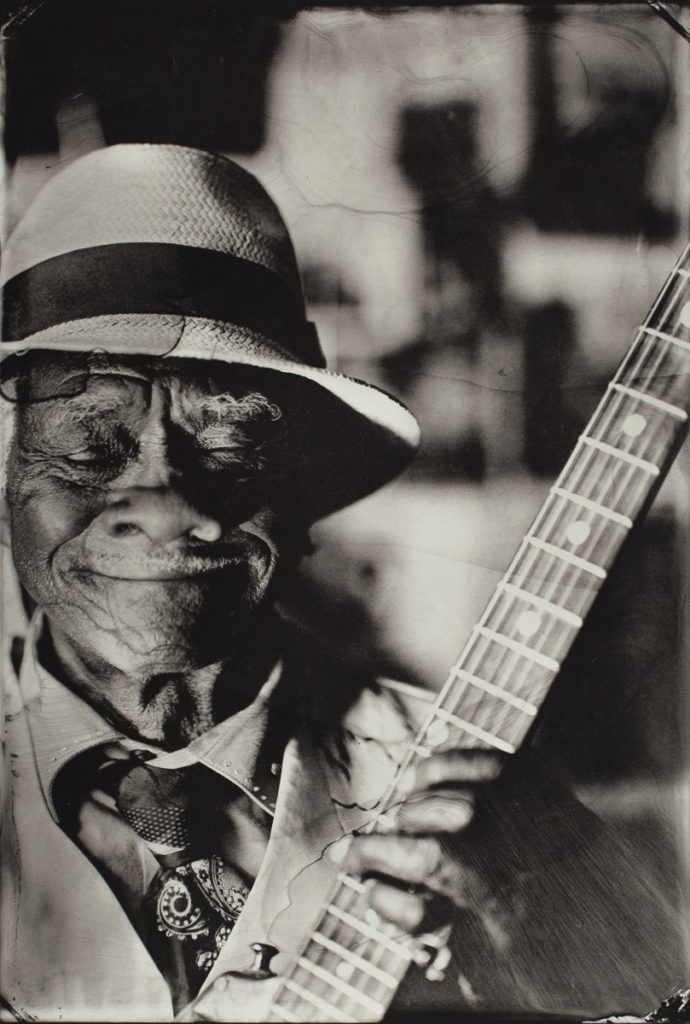

“Why Am I Treated So Bad?,” The Staple Singers (1966)

The Staple Singers met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 after a performance in Montgomery, Alabama. Roebuck “Pops” Staples, the band’s patriarch, said afterwards: “I really like this man’s message. And I think if he can preach it, we can sing it.” The group went on to write and perform many Civil Rights songs, including “March Up Freedom’s Highway” and “Washington We’re Watching You.” “Why Am I Treated So Bad” was written in reference to the treatment of the nine African American children at the forefront of integration in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. It became a particular favorite of King’s and was often sung before he spoke to a crowd.

“We Shall Overcome,” Mahalia Jackson (1963)

One of the most well-known songs of the Civil Rights movement, “We Shall Overcome” exemplifies the resilience, determination, and hope of the activist leaders and the everyday protesters alike. Its origins stretch back to the early 20th century with Charles Tindley’s “I Will Overcome.” Striking workers took up the song in the 1940s, later sharing it with Zilphia Horton at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, a center for social justice and activism. White and black activists came together at Highlander for workshops and planning during the Civil Rights movement, and some of that work involved learning songs and how to employ them in protests. Musical director Guy Carawan learned a version of the song from Pete Seeger; Carawan later introduced the song at the founding convention of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. (To hear Candie Carawan talk about the work at Highlander and the power of music during the Civil Rights movement, check out December 19’s archived On the Sunny Side show on Radio Bristol; her interview is towards the end of the show.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vTyKJjj2oC0

Finally, did you know that there is a connection between Carter Family favorite “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” and civil rights? The song has been sung by various activist musicians, including Jimmy Collier and the Movement Singers and Freedom Singer Bernice Johnson Reagon, and an audio history of the Civil Rights movement takes the song title on as its name.

Rene Rodgers is the Head Curator of the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

What is your recurring dream?

What is your recurring dream?