January 6 is National Technology Day – and so it seemed the perfect time to explore some of the Birthplace of Country Music Museum from the technology side of things! We’ve picked five elements of the content or the museum itself that tell just a little of the technology story here:

Recording and Playback Machines

The museum shares the story of the 1927 Bristol Sessions, but it also explores how sound technology shaped their success and evolved over the years. Inventions such as recording and playback machines played important roles. For instance, in 1877, Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, which was instrumental in distributing music in the early 20th century, including the songs recorded at the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Writing an article in 1878 on “The Phonograph and its Future,” Edison listed other possible uses for his invention beyond playing music, including elocution and other educational lessons; audio books (before Audible and iTunes!); to create sound effects for children’s toys; and most intriguingly, “family records,” where the last words of dying family members could be saved for posterity, like that of other great characters of the day.

Other innovators contributed to the development of this type of playback technology. In 1881, Alexander Graham Bell invented the graphophone, an improved version of the phonograph developed by Edison, and in 1894, Emile Berliner invented the disc gramophone method, which used different machines to record and then to play back the sound. Where earlier recording and playback machines used cylinders, either coated in tin foil or wax, Berliner’s gramophone used flat disc records.

The museum is a high-tech, interactive experience, one that is filled with music and sound. And because of that, it had to be designed strategically and carefully in order to provide the best possible experience to our visitors. For instance, the acoustic engineer advised the architects and exhibit designers on ways to define walls and ceilings to contain sound or keep it from bouncing around the open gallery spaces or the theater. The firm also worked closely with the technology team and media producers to define how the sound of each audio or audio/video production is delivered into the space. The goal was to provide an immersive experience, yet minimize unwanted “bleed” of sound between programs. Innovative acoustic wall panels and fabric mean that the acoustic technology is seamless and becomes a part of the museum experience itself, while speakers embedded underneath the pews in the chapel theater space mean that visitors feel like they are right in the middle of the congregation and they can often even feel it in their seats!

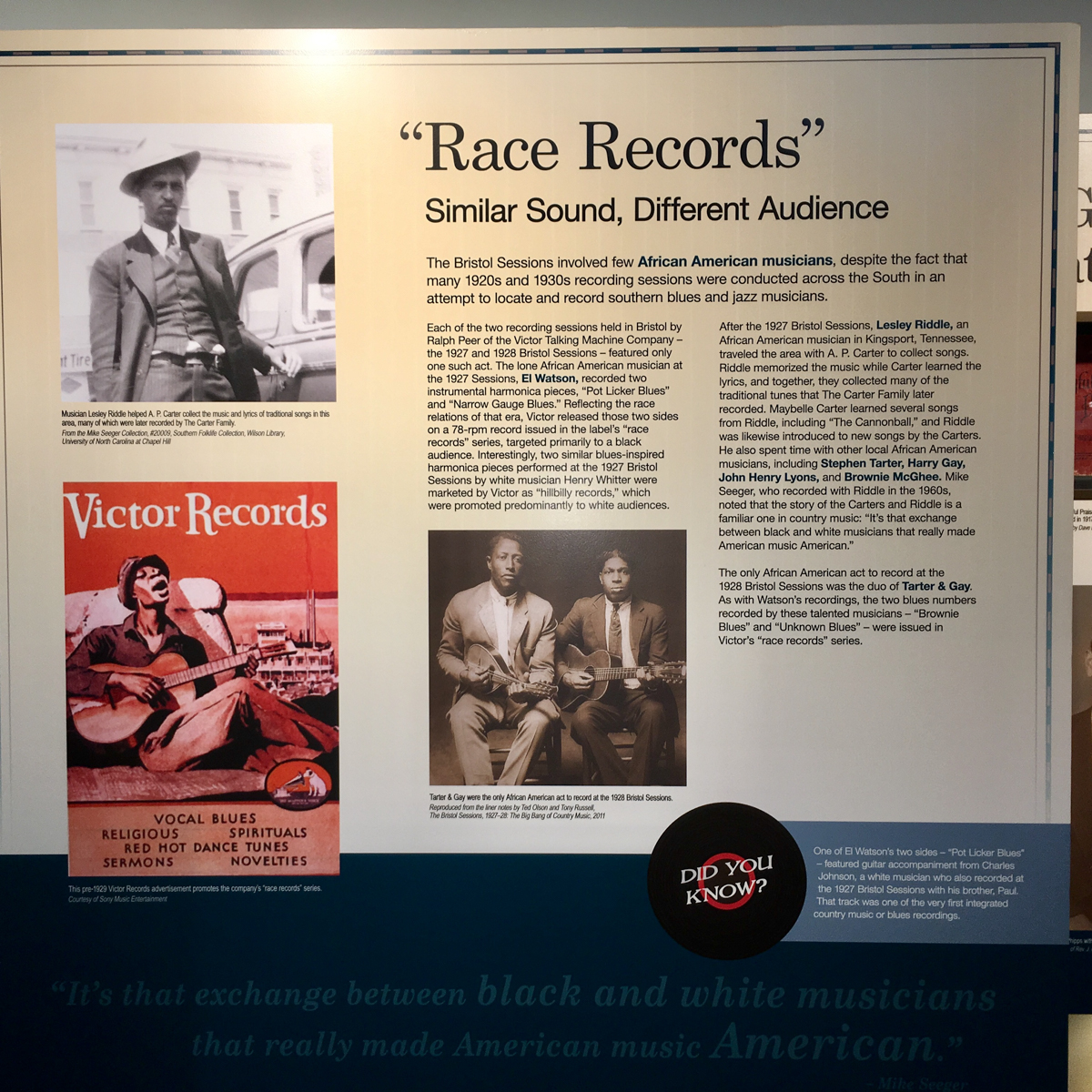

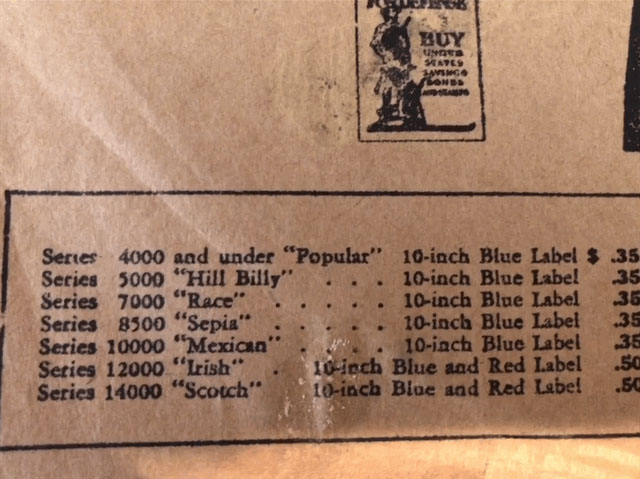

Orthophonic Technology

Orthophonic reproducers were an outgrowth of the electric microphones being used to record performers in the late 1920s. Electric recording captured a wider range of sound frequencies and produced recordings in which the instruments and voices sounded much more like live instruments and voices than they had on previous acoustic recordings. These reproducers were designed to be more sensitive to the nuances in the electric recordings, making the listener’s experience more pleasurable and true-to-life. The Bristol Sessions in 1927 were recorded using this process and many claimed that the Orthophonic recordings sounded even better than the live performances! Electric recording and Orthophonic machines, like later compact discs or HDTV, were a technological revolution that helped change the shape of the music industry.

The Radio Station

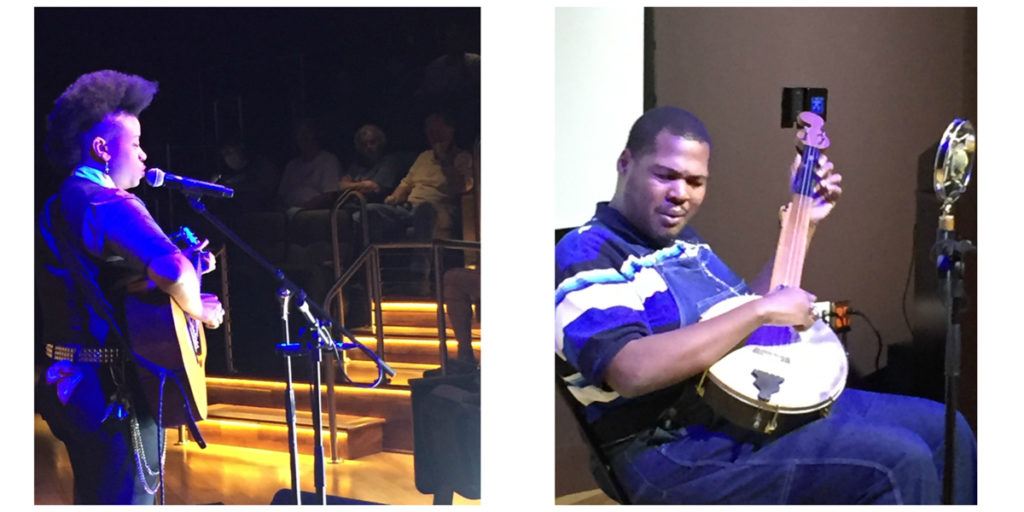

During the planning stage of the museum, the exhibit content team discussed ways to make the space focused on radio history into an engaging experience for our visitors. The result? Radio Bristol, a live radio station! With help from a team of radio industry advisers, BCM applied to the FCC for a low-power FM license, secured the antennae, transmitter and equipment necessary for broadcasting, and created a working radio studio in the museum. And that’s where the technology gets really interesting because the station uses vintage equipment from older Bristol radio stations, refurbished and repurposed for today. For instance, a Raytheon console from 1940s WCYB Radio, sourced from local radio buff and collector William Mountjoy, was rebuilt by engineer Jim Gilmore, retired engineer from TNN. One of the mics in the radio studio is from local station WOPI and was used by Tennessee Ernie Ford when he was a DJ there. And there are numerous ways to deliver music in the station – from a record turntable to a live recording booth to the digital ease of tablets and MP3s. The station is what we call high-tech vintage!

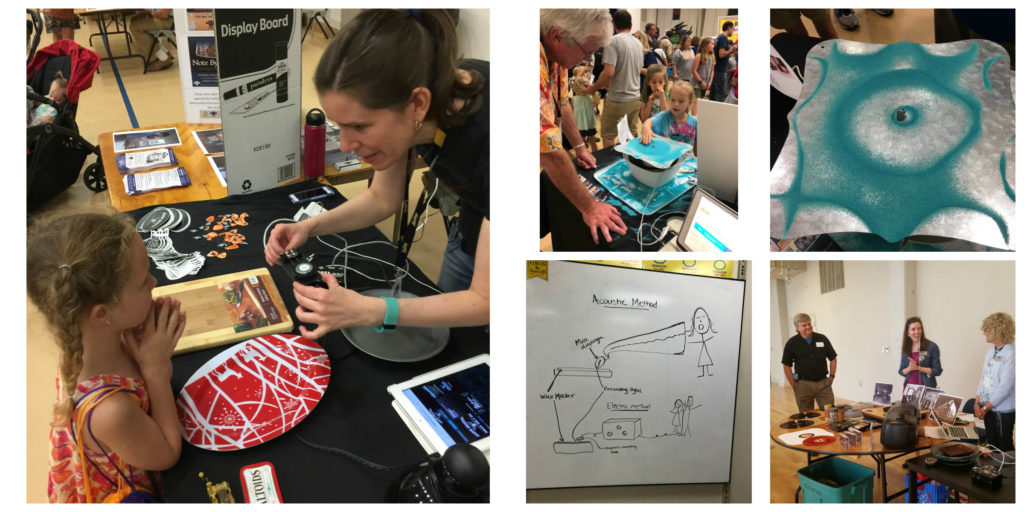

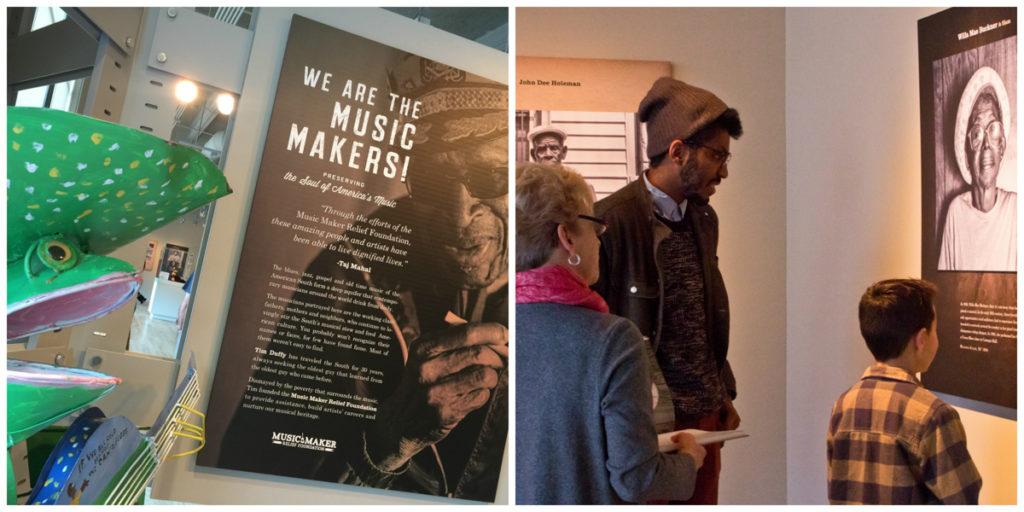

Technology Lessons

Finally, sometimes the technology isn’t an object from our collections or an innovative way to present the museum’s content. Rather it is found in educational programs where we share the story of that technology. For instance, for the past two years, museum staff and volunteers have participated in the Kingsport Mini Maker Faire where we have presented information about the museum’s exhibits and engaged in a variety of sound demonstrations, including an example of amplification and a homemade Chladni plate! We also offer a “History of Listening” lesson, available in the museum and to schools and other groups. Throughout history music has been experienced in a variety of ways, especially as advances in technology have developed over time. This lesson explores these technological changes and then compares how listening to music transitioned from being a mostly community-based activity, often through live performance, to listening either alone or together in person via technology and the virtual environments of cyberspace.