Murals are one of the oldest known forms of human artistic expression. What people decided to paint on the walls of their domestic and community spaces can tell us a lot about the time and society in which they lived. For example, in the first known cave painting made in Indonesia 45,500 years ago, humans depicted animals and other humans they interacted with every day. During the Renaissance, murals of great religious scenes were painted on the walls and ceilings of churches, underlining the political, cultural, and financial power of the church during the 16th century. And, within the 20th century, we have seen a dramatic rise in murals being made for arts-sake, to make a political statement, or to highlight local color and culture.

So, let’s take a look at some murals that are special for all of the aforementioned reasons and because they tell a story you’re probably interested in if you’ve found your way to this blog: the story of country music.

Courtesy of Eddy Gray, Tri Cities Captured Photography

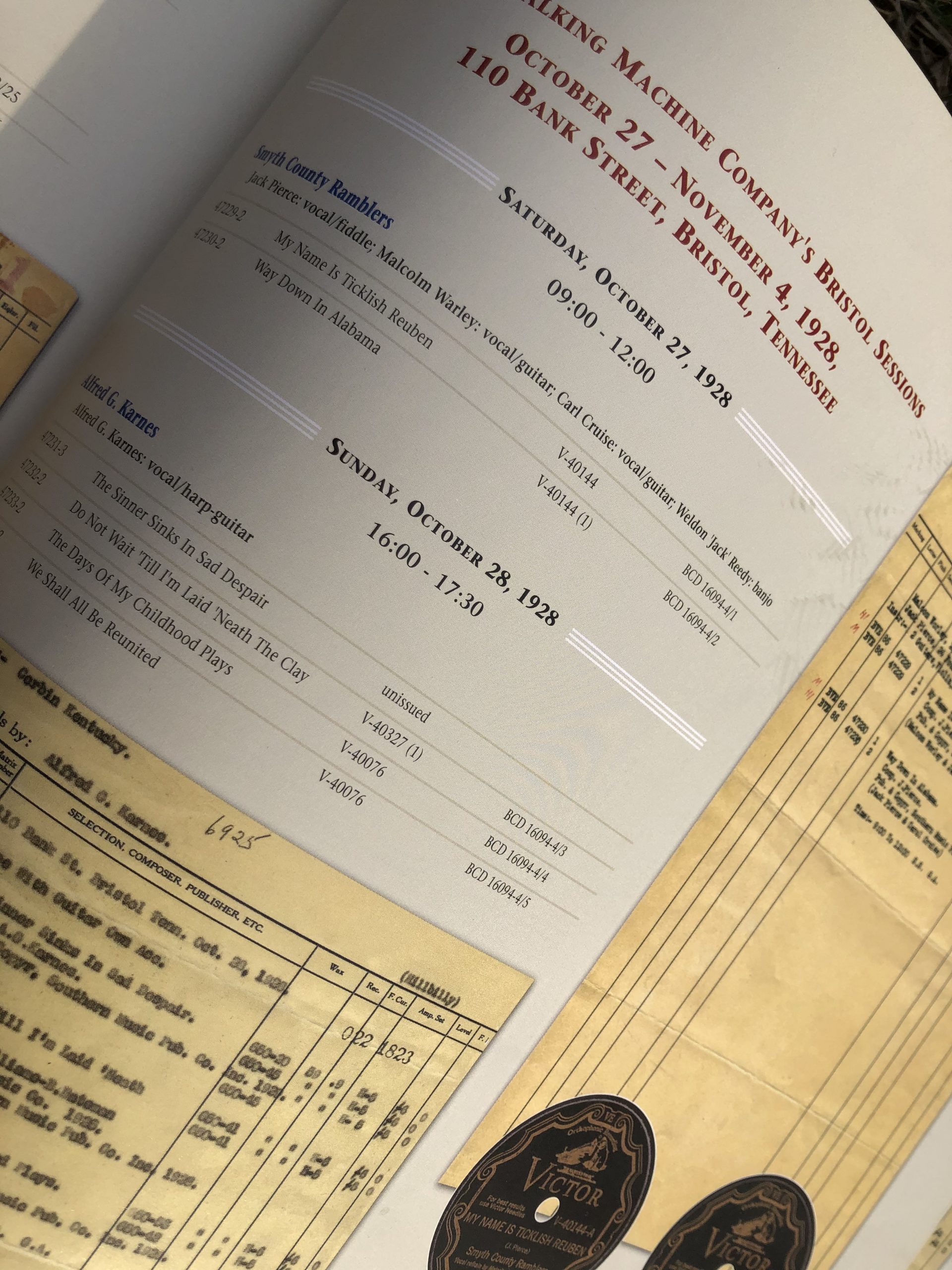

We’ll start with a mural that is a Bristol, Tennessee-Virginia must-see: Bristol’s Country Music Mural. The mural is located at 810 State Street, a public square that is used for the weekly farmers’ market, community events, and to host one of the stages at Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion. The mural is 30 feet by 100 feet, taking up the entire side of a building, and features the big players and iconic images from the 1927 Bristol Recording Sessions: Ralph Peer, The Carter Family – A. P., Sara, and Maybelle, a Victor record and microphone, Ernest and Hattie Stoneman, and Jimmie Rodgers. First painted in 1986 by local artist, musician, and radio DJ Tim White, the mural was recently refurbished to great effect during the summer of 2020.

Source: Knoxville Public Arts

Next stop on our virtual tour of murals with a country music connection is the Knoxville Music History Mural. The mural is located at 116 East Jackson in Knoxville, Tennessee, and it was designed by Knoxville artist Walt Fieldsa in collaboration with local art teacher Tifanni Conner and her students at Laurel High School. The mural was then painted by local artists, including Fieldsa, Randall Starnes, and Ken Britton. The painting depicts several Tennessee musicians, including operatic singer Grace Moore, composer and pianist Richard Trythall, founder of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra Bertha Walburn Clark, guitarist Willie Sievers of the Tennessee Ramblers, jazz pianist Donald Brown, rock singer Tina Turner, and bluegrass musician Jimmy Martin.

Courtesy of Theron Corse, Nashville Public Art blog

We come next to the Nashville Fences of Fame located on several fences surrounding Columbine Park in Berry Hill. The project of painting these fences of the musical greats began in 2016 by artist Scott Guion and was commissioned by The House of Blues. A wide array of musicians from incredibly different genres are painted throughout the area – for instance, one fence alone depicts Jim Lauderdale, Nina Simone, Emmylou Harris, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Greg Allman, Jerry Garcia, Joni Mitchell, and Otis Redding.

Photograph © Denise Smith

In 2014, artist Jeff Pierson painted a wonderful mural depicting the 1927 Bristol Sessions artist Blind Alfred Reed on a brick wall on Mercer Street in Princeton, West Virginia. Pierson was commissioned by Princeton’s Community Improvement Committee to paint a series of important folks from Princeton on various walls around town. While researching Princeton local legends, he came across information about Blind Alfred Reed and was taken aback to learn his interesting story. When he proposed making Reed the subject of one of the murals, the committee didn’t even know who Reed was – but they were soon convinced of his importance and in due course his likeness could be found on one of the city’s walls as public art! Due to the demolition of the building, the mural is being moved to a new site in the town.

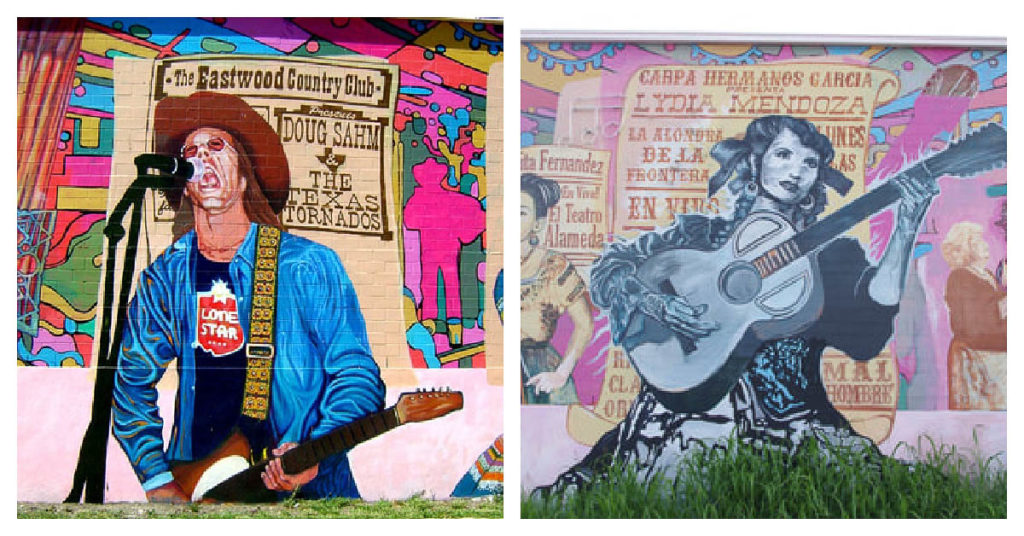

Source: San Anto Cultural Arts website

Next up is the San Antonio Gateway Mural, locally known as La Musica de San Anto. Located on the west side of San Antonio, the mural was painted in 2008 by local artist David Blancas after it was commissioned by San Anto Cultural Arts to bring awareness to the musical heritage of San Antonio. The mural features members of the country band “The Texas Tornados” and Tejano (a style of music derived from Mexican-Spanish vocal traditions and Czech and German dance music) musicians such as Lydia Mendoza, amongst others. A contemporary of Mother Maybelle Carter, Mendoza also played on the border radio station XERA. (Check out this fascinating article about the similarities between Mother Maybelle and Lydia Mendoza from NPR.)

Image sourced from a review on TripAdvisor

Another great mural can be found at the West Tennessee Delta Heritage Center in Brownsville, Tennessee, which also includes the Tina Turner Museum. In 2014 a mural of Brownsville natives Tina Turner and Sleepy John Estes was painted on the side of the museum by Union University art students. And while Sleepy John Estes is a well-regarded blues artist that influenced musicians like The Beatles, and Tina Turner is more well-known as “The Queen of Rock-n-Roll,” I would argue this is a bona fide country music mural because Tina Turner made her musical debut as a solo artist with a country album in 1974! If you haven’t listened to Tina Turns the Country On!, I highly recommend turning the record on now!

Last but not least on our grand country music mural tour is a painting of Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion 2021 headliner Tanya Tucker. You can find the mural in Spirit Square in the “Country Music Capital of Canada”: Merritt, British Columbia. The wall-sized portrait of the singer was painted by local artist Michelle Loughery and members of the Merritt Youth Mural Project, a program designed to work with local young artists and “youth at risk.” Tucker was even there for the unveiling of the mural in 2006!

This post highlights just a few of the music heritage murals out there, but it’s a great introduction to this highly visible and community-driven public art. Murals are a fascinating look into our history and culture, and you can learn more about the history of murals with this article from The Community Rejuvenation Project in the Bay Area. And, I wanted to give an honorable mention to some local mural trails: The Mountain City Music Mile and The Appalachian Mural Trail.