Our Radio Bristol DJs are a diverse bunch – and they like a huge variety of musical genres and artists. In our “Off the Record” posts, we ask one of them to tell us all about a song, record or artist they love. Today we hear from Brody Hunt, host of Land of the Sky, as he tells us some tales about hoboes and their songs.

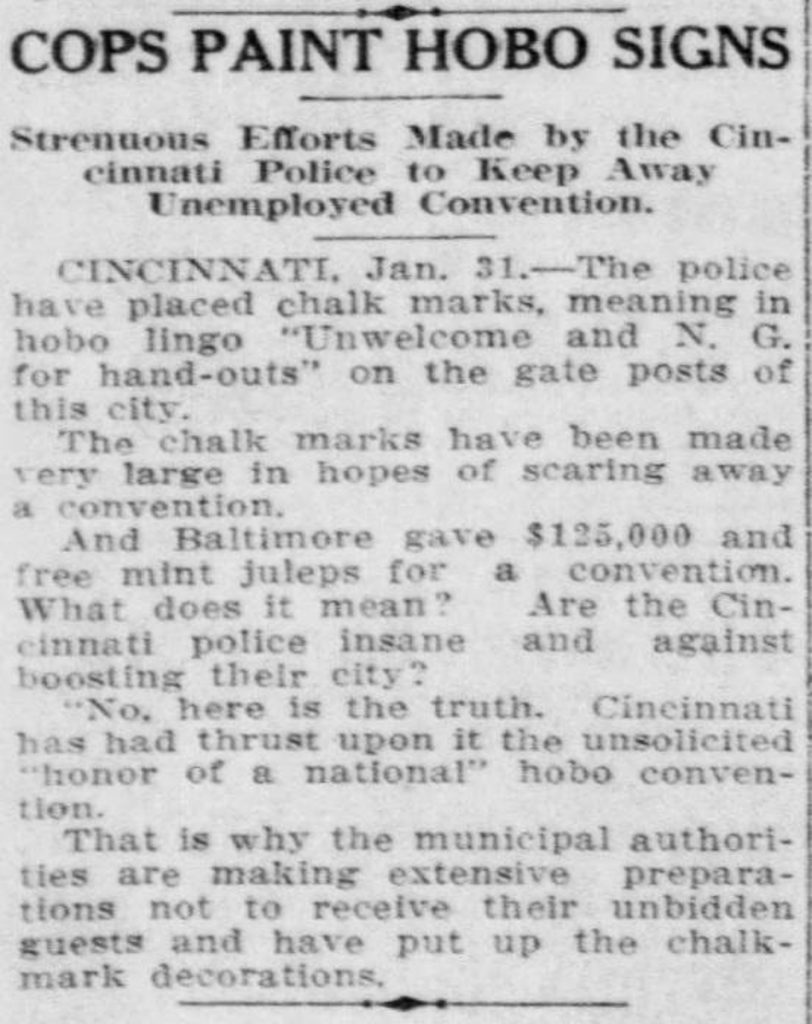

One of the public’s most enduring fascinations with the American hobo tramp is their fabled system of mysterious and secretive signs or codes. The concept of carved or chalked hobo hieroglyphics left by a Knight of the Road for his fellow Brethren of Bumdom, warning of a lousy calaboose (that is, a local jail) or showing where to find a kind woman for a handout, just won’t fade. Newspapers of the classic hobo era printed countless articles about hobo signs, seemingly a surefire way to sell a sheet. Tramps themselves were at times interviewed and enticed to divulge these secret signs for publication, doubtless in trade for a solid feed or a pint of gin. In one instance, the local town clowns themselves even made use of hobo signs in an attempt to detour a convention of ‘boes around their city.

A 1912 article in the St. Louis Star and Times records how the Cincinnati police painted hobo signs as a way to deter hoboes from coming into the city.

But are there solid facts that confirm the widespread use of hobo signs? The Historic Graffiti Society has recently published their remarkably well researched Hobo Signs Zine, and an excerpt of their conclusion reads:

In our opinion, hobo signs were not the secret language of hoboes. While they definitely found a place in popular culture, mainly thanks to newspapers throughout the decades, there is little to no concrete evidence to prove their existence. It is possible that a very simple set of signs (good, bad, safe, dangerous) were used by a small minority of the traveling population, but nothing that ever took hold or was widespread. The real language of the hoboes was, and is still to this day, word of mouth. Information including what towns were hostile and where a hobo could find work traveled up and down the railroad lines without the need for signs and symbols… In our travels we have documented over 1,000 individual pieces of hobo graffiti. These marks generally contain the hobo’s moniker (assumed name), the date the mark was made, and the direction of travel. For how many instances of hobo moniker marks we’ve found and documented, we have never come across a single hobo sign. Perhaps the Oregon Daily Journal said it best in 1907, stating that the only secret sign is “Help Wanted” and that “It is so baffling that the average tramp never tries to fathom its depth.”

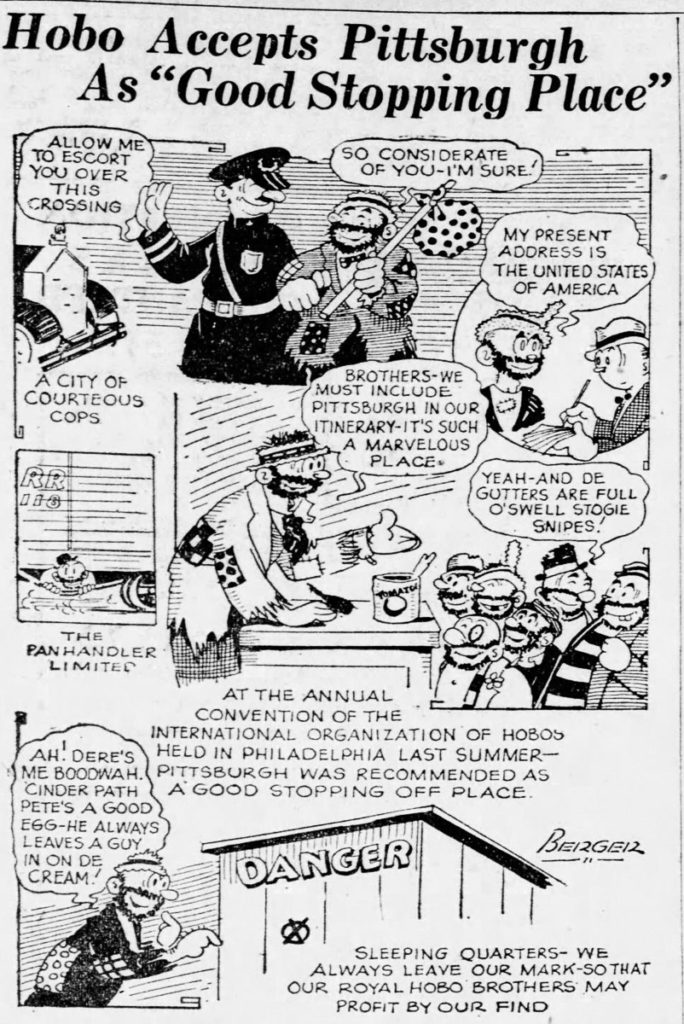

Newspaper cartoon from the Pittsburg Press, 1927.

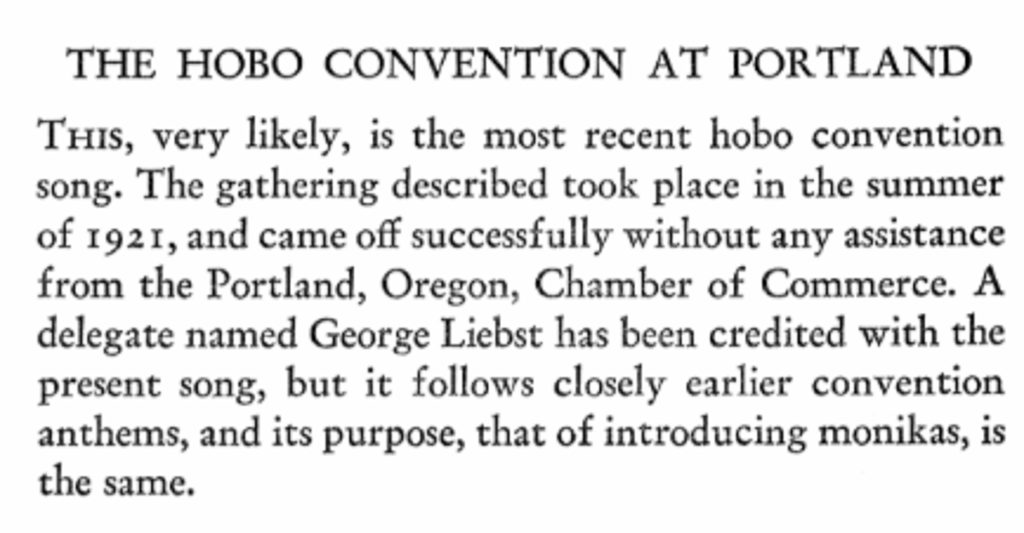

While the myth of hobo signs will undoubtedly persist as long at the hobo retains even the smallest nook in the American psyche, the use of nom-de-rails by those who work and inhabit the rails also endures. Freight cars today are often covered in spray paint graffiti, but a closer look will quickly reveal the grease-paint monikers of railroad workers and train riders alike. Even if they don’t mark a substantial number of rail cars or other trackside canvases, nearly everyone who spends more than a year or two bumming on the rails eventually ends up with a moniker, often with a distinctive character or symbol. In the summer of 1921, Portland, Oregon was the scene of a hobo convention resulting in a moniker song that has left a small impression on hobo balladry. Titled “The Hobo Convention at Portland,” the song is included in George Milburn’s 1930 volume of tramp prose, The Hobo’s Hornbook. His introduction to the piece is seen below, followed by the printed lyrics.

You have heard of big conventions, And there’s some that can’t be beat, But get this straight, there’s none so great As when the hoboes meet. To Portland, Oregon, that year They came from near and far; On tops and blinds where cinders whined And hanging to the drawbar. Three hundred came from New York State, Some came from Eagle Pass; That afternoon, the third of June, They gathered there en masse. From Lone Star State came Texas Slim And Jack the Katydid. With Lonesome Lou from Kal-mazoo Came San Diego Kid. And Denver Dan and Boston Red Blew in with Hellfire Jack, Andy Lang from longshore gang, Big Mack from Mackinac. I saw some ‘boes I never met; A ‘bo called New York Spike, Con the Sneak from Battle Creek And Mississippi Ike Old Joisey Bill, dressed like a dude, Shook hands with Frisco Fred, And Half-breed Joe from Mexico Shot craps with Eastport Ed. St. Looie Jim and Pittsburg Paul Fixed up a jungle stew While Slip’ry Slim and Bashful Tim Creaked gumps for our menu. Then Jockey Kid spilled out a song Along with Desp’rate Sam; And Paul the Shark from Terror’s Park Clog-danced with Alabam. We gathered ‘round the jungle fire, The night was passing fast; We’d all done time for every crime, And talk was of the past. All night we flopped around the fire Until the morning sun; Then from the town the cops came down, We beat it on the run. We scattered to the railroad yards And left the bulls behind; Some hit the freights for other states And many rode the blind. Well, here I am in Denver town, A hungry, tired-out ‘bo; The flier’s due, when she pulls through, I’ll grab her and I’ll blow. That’s her—she’s whistling for the block— I’ll make her on the fly’; It’s number nine—Santa Fe line. I’m off again—Goodbye!

The Oregon Daily Journal announced in a headline “Railway Police Declare War on Brakebeam Rider” the following September. It seems doubtful this was a result of the Portland convention. The cinder dicks, or railway police, were and will always be unsuccessful with their goal of the “Elimination of Every Weary Willie.”

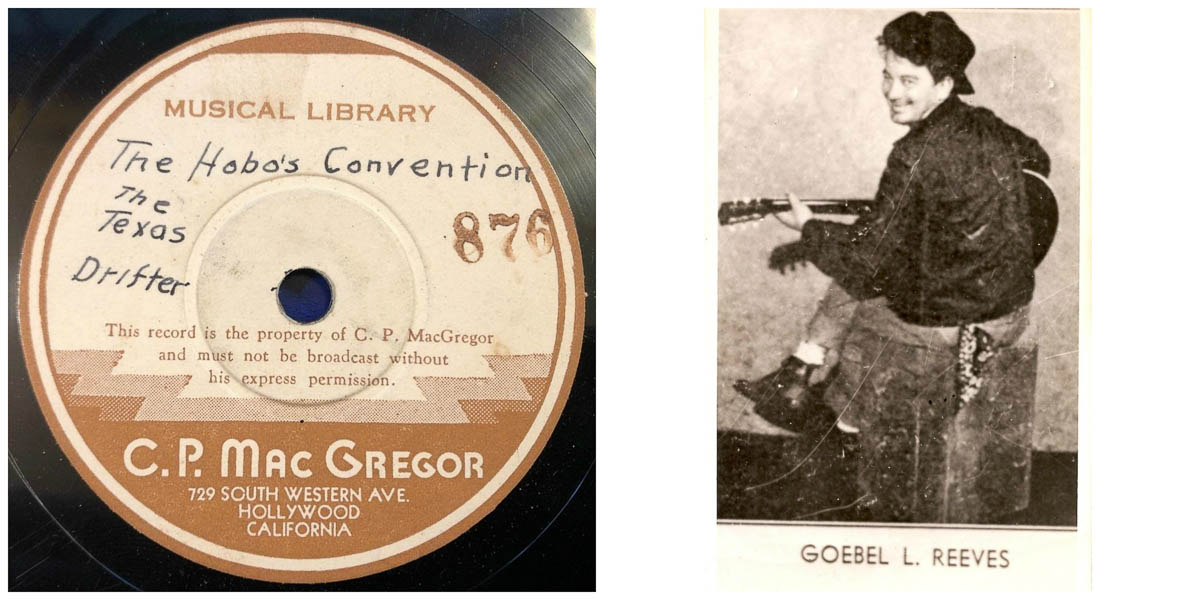

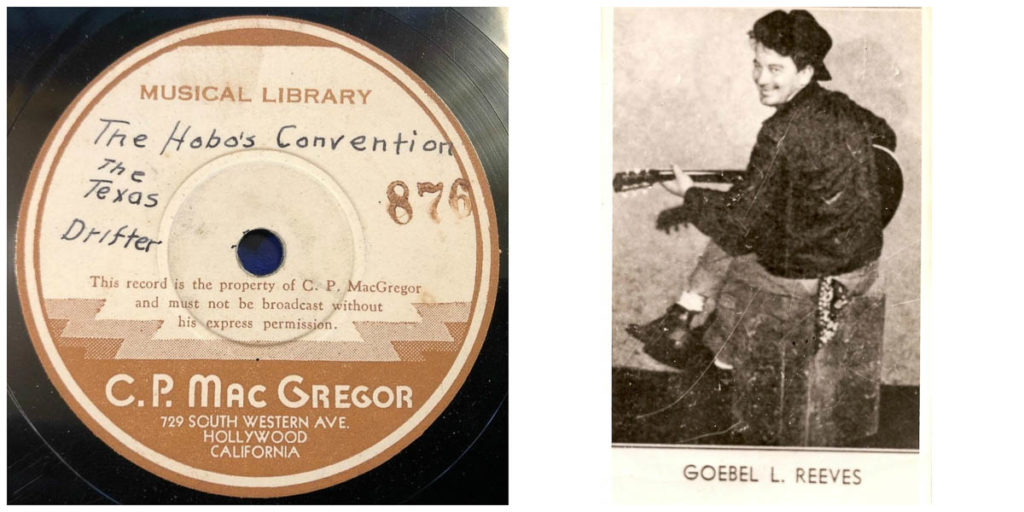

Two songs titled “The Hobo’s Convention” were recorded onto 78rpm discs in the 1930s. One with lyrics nearly identical to those in Milburn’s book was recorded by Goebel Reeves for C. P. MacGregor in Hollywood, California, in either 1938 or 1939. This disc, with hand-stamped catalog number and handwritten artist and song credits, was not meant for commercial consumer release, but intended for radio broadcasts. Reeves, or “The Texas Drifter” as he was sometimes known, was indeed a Texan from the burg of Sherman. By the time he cut the MacGregor disc, Reeves had already been traveling the country since 1929 as a hillbilly radio entertainer and recording artist. Wounded in action in World War I, Reeves took up tramp life upon his return to the States and may well have learned the song on the road, or even been at the Portland Convention himself. At any rate, it is a pleasure to have a hard-boiled ex-hobo on record singing the piece. You may listen to his record here: https://soundcloud.com/brody-hunt-138211625/goebel-reeves-hobos-convention.

Record label for “The Hobo’s Convention” by Goebel Reeves, known as the Texas Drifter, and a photographic portrait of the musician. Record label image from the author’s collection; portrait from the collection of Tony Russell

An earlier recording of “The Hobo’s Convention” is more elusive, but there is a version that was waxed in 1932 by Boyden Carpenter, known as “The Hillbilly Kid,” who was raised around Cherry Lane, North Carolina. It was possibly similar to the above, or at least some form of moniker song. Although it’s unclear if he ever flipped a freight, Carpenter certainly had an adventurous spirit and a strong taste of beating his way across the country as he attempted to start a career in radio during the onset of the Great Depression.

In Carpenter’s own words he describes leaving the mountains bound for the broadcast powerhouses of Chicago:

Well, Folks, it was back in 1930 that I decided to leave Alleghany County and get on the radio. Most of the programs coming in on the old battery set down at John Miles’ store was comin’ from Chicago, so that’s where I headed for. Now I didn’t have but a few dollars, but I’d been savin’ my nickles and dimes, in case I’d need a little money on my trip, but I didn’t have enough money for a ticket to Chicago. I got my ma to fix me up a few pones of bread, a rasher of meat, and some Irish potatoes, and I struck out for the big city on foot. I never will forget the way the fellers laughed at me as I passed down there at Miles’ store. They all said “There he goes, he ain’t got no sense, why they’ll have him in the asylum before he gits out of Alleghany County. That boy will never amount to a hill of beans out runnin’ around over the country, why he’d better stay around here and work on a farm.” Why I just paid no ‘tention to them fellers and kept on my way. Now, it wasn’t long before my rations that I left home with played out, so I had to find little odd chores, such as cutting wood and things like that for a meal here and there. You know I didn’t want to beg for a handout, and be a regular bum, I wanted to make my way… Yeah on that trip to Chicago I slept in straw stacks, hay lofts, depots and a little of everywhere. Well, rides was mighty scarce on that trip, and I don’t blame them folks for passin’ me by so much ‘cause I wasn’t such a good lookin’ prospect fer company. So, as much as I had to walk, it tuk me right at thirty days to get to Chicago.

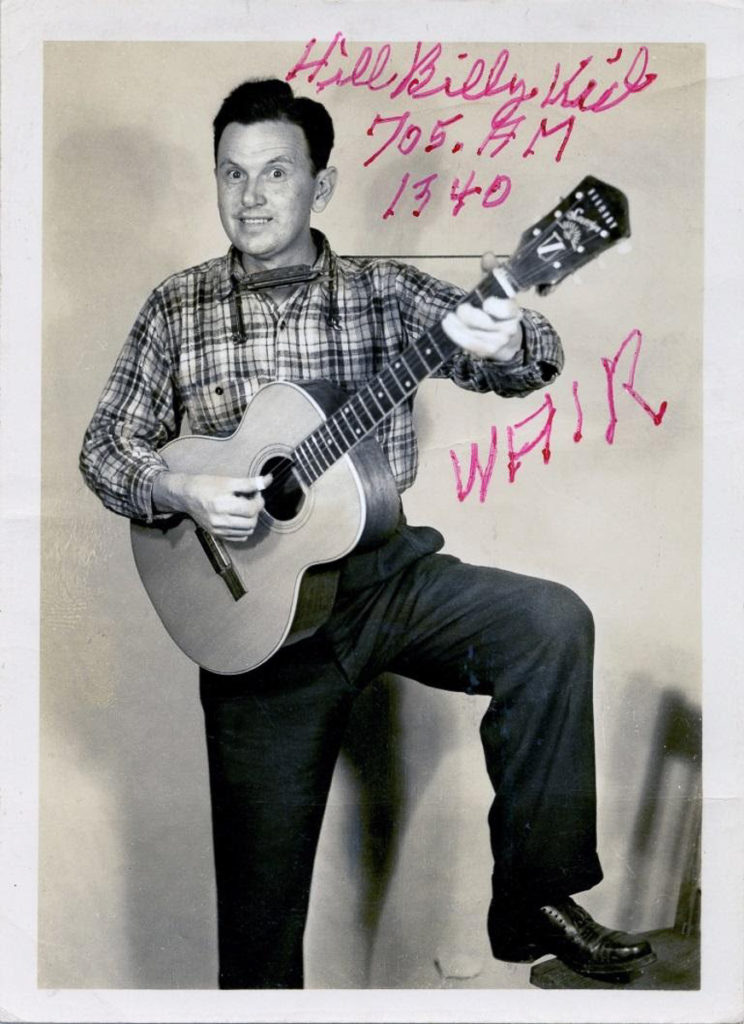

Promotional photograph of Boyden Carpenter, also known as “The Hillbilly Kid.” From the collection of Marshall Wyatt

After three days of finding no interest in “what I had brought with me from Allegheny County,” Carpenter started walking back home. On this return trip, he eventually landed his first radio job on WCKY in Covington, Kentucky. In his “drifting days,” he would go on to work the airwaves of WHAS, Louisville; WKRC, Cincinnati; WFBM, Indianapolis; WJJD, Chicago; WIOD, Miami; WDBO, Orlando; WJAX, Jacksonville; WMBR, Jacksonville; and WFBC Greenville. He then broadcast for Crazy Water Crystals on WGST and WSB, Atlanta; WMAZ, Macon; WBT, Charlotte; and WPTF, Raleigh, before moving on to WAIR, Winston-Salem.

Boyden Carpenter twice recorded for Gennett Records at their Richmond, Indiana studios. On the first trip, he accompanied the blind North Carolina street singer Ernest Thompson on the hitchhiking journey up north, and both men recorded on January 22, 1930. (This date is seemingly at odds with Carpenter’s account of first leaving home on the bum alone in 1930. More realistically, his first trip out of the mountains was actually in 1929.) The two sides that Carpenter waxed were rejected, but he returned to Richmond and recorded two more sides, including “The Hobo’s Convention,” on September 13, 1932. By this time Gennett was in a state of economic collapse, with individual record sales at times below 100 copies. The coupling of “The Hobo’s Convention” with “The Old Grey Goose Is Dead” was given a catalog number on Champion, a Gennett stencil label. Shipping figures are not available for Champion 16519, and no copies of the 78 are known to exist.

* Special thanks to the Historic Graffiti Society, Jonathan Ward, and the research of John Edwards, Charles Wolfe, Tony Russell, Bob Carlin, and Marshall Wyatt, all integral to the content of this “Off the Record” post. The Historic Graffiti Society’s Hobo Signs Zine may be found here.