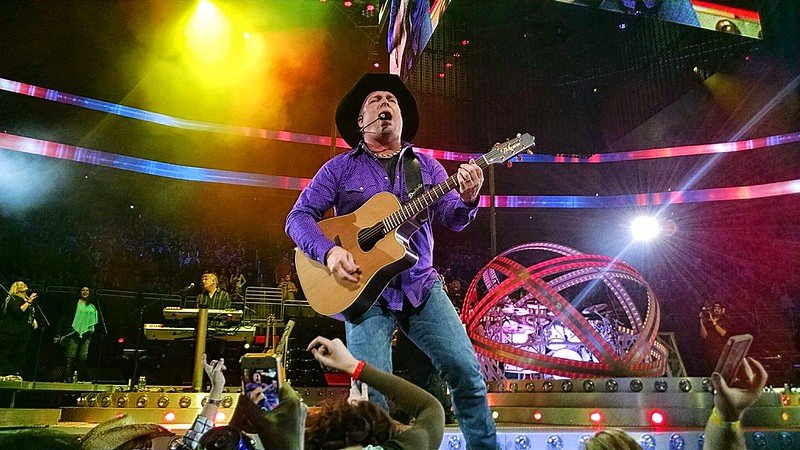

Perception has always been integral to country music. From the very beginning with Fiddlin’ John Carson’s debut in Okeh Record’s “Old Familiar Tunes” catalog to Garth Brook’s record-breaking stadium tours, the way country music has been marketed to the public has relied heavily on its appearance. It’s been something the genre has taken with pride, shunned with disdain, or constantly parodied throughout its history.

One of the most common perceptions about country music is the idea of the stereotypical country singer as a “lonesome cowboy” singing in a smoke-filled honky tonk to beer-drinking, blue collar workers in nasal, piercing tones. However, in the early 20th century, country music catalogs were filled with images of overall-wearing “hillbillies” playing fiddle and banjo breakdowns for square dancers in plaid shirts and gingham dresses. In the 1920s, country music was marketed to a specific type of audience, though of course, that did not mean that this specific audience was the only one buying the records. These listeners were conceived as displaced ruralites who saw the rapidly changing landscape around them as too fast-paced and carried with them a nostalgia for earlier times, times when parlor songs and mountain reels dotted the backcountry of Appalachia.

Record companies, therefore, often encouraged their artists to “play up” their rural heritage and soon records by groups with homespun names like Al Hopkins and His Hillbillies, Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers, and Uncle Dave Macon and the Fruit Jar Drinkers started selling by the thousands. Some of the first entertainment outlets to notice this association with country music and a created image or persona were the radio “barn dance” programs that were growing in popularity in the late 1920s. Radio listeners quickly developed attachments to their favorite performers, and soon, fans were showing up in droves outside of studio air rooms to catch a glimpse of this new genre of radio star. To keep alive the illusion of a “Good-Natured Get Together,” George D. Hay – founder of the WSM Barn Dance in Nashville (soon to be renamed as the Grand Ole Opry ) – sent a memo to his performers of string bands and soloists to encourage them to wear work clothes and straw hats. And over time he renamed his “string orchestras” to more hillbilly titles such as Dr. Humphrey Bate and His Possum Hunters and Paul Womack and the Gully Jumpers. Soon, The Grand Ole Opry stage was dominated by “hoedown bands” and remained largely that way until the late 1930s.

Meanwhile in Chicago, the WLS National Barn Dance had a brand-new star on its own barn dance show. Inspired by Jimmie Rodgers and western poets such as Jules Allen and Carl T. Sprauge, yodeler and guitarist Gene Autry was bringing the heroic idea of the American cowboy to audiences across the country. Clad in a 10-gallon Stetson hat and strumming a plaintive guitar, Autry soon brought Depression-era audiences to a frenzy with his move to Hollywood to become “America’s Singing Cowboy,” inspiring future generations of country musicians to don cowboy hats and western wear.

Soon, this image of a cowboy’s life was adopted by fellow WLS star Patsy Montana, bringing “girl singers,” as they were called, to the fore – and offering a new image, independent of Mountain Men and traditional gender roles, in the romanticized image of the cowgirl. Patsy’s long cowhide skirt and pushed back cowboy hat embodied her free and adventurous spirit, characterized by her anthem “I Want to Be A Cowboy’s Sweetheart.” Overnight, female country performers dropped the gingham dress, “milk maid,” “pure mountain gal” personas for the exciting image of the American cowgirl.

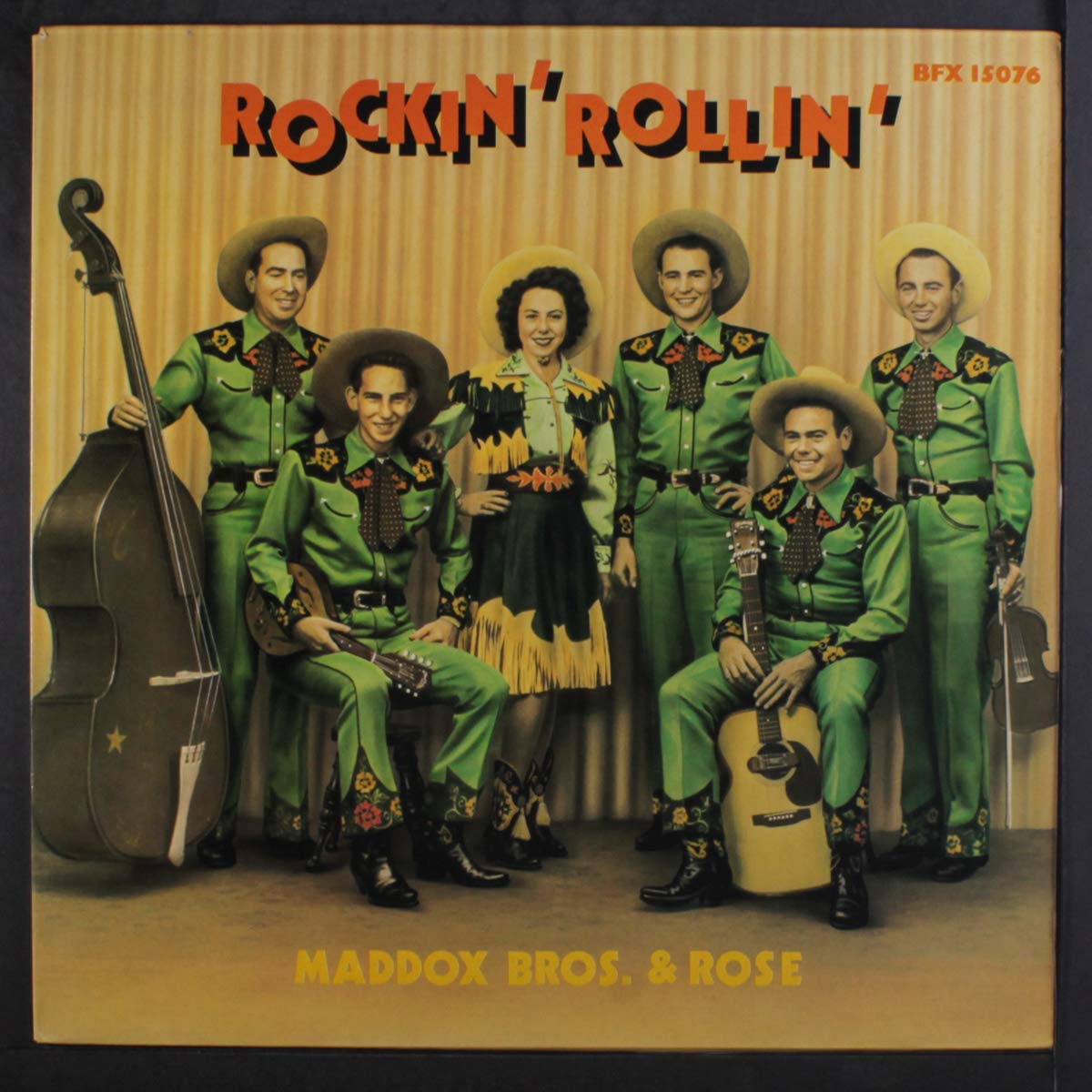

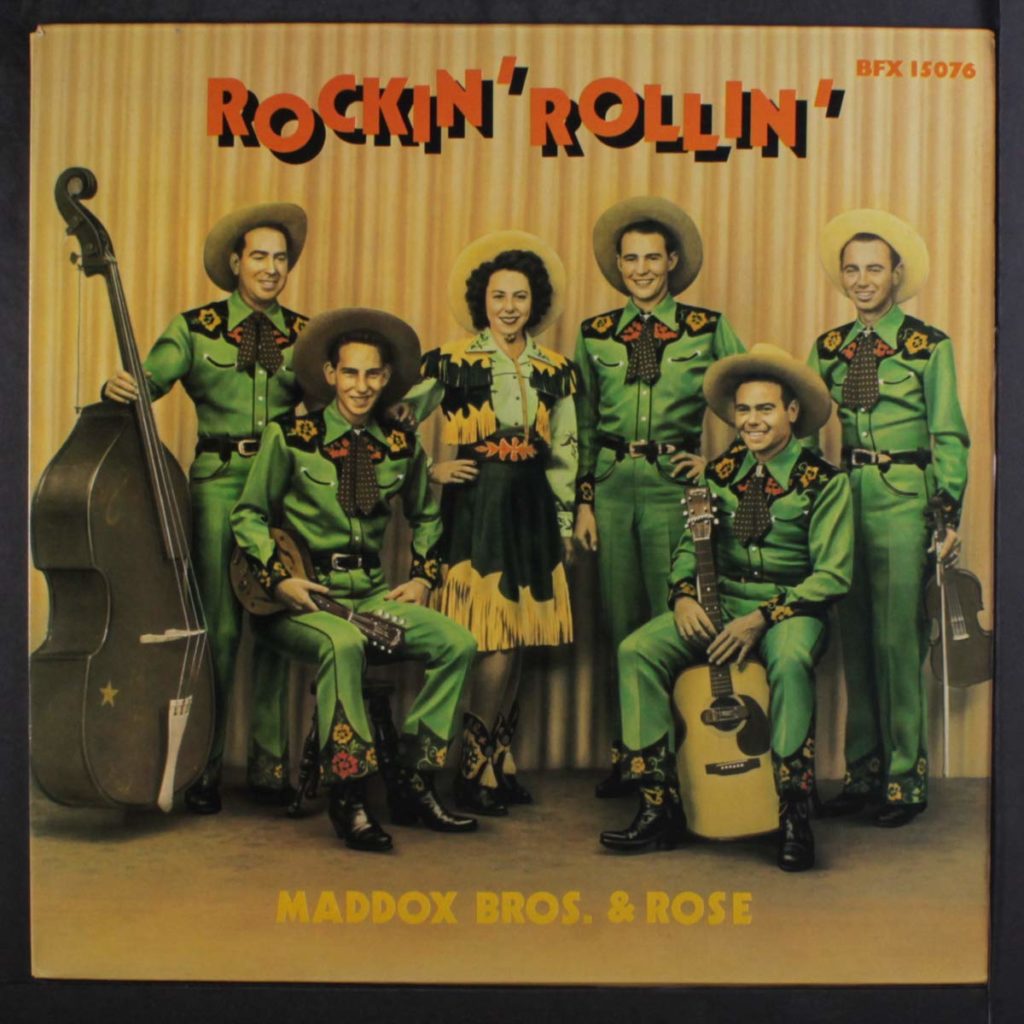

Among this new group of independent female performers was Rose Maddox, who, along with her brothers, pushed hillbilly and cowboy performance to new heights with their eccentric and electric performance style. The Maddox Brothers & Rose grew to prominence on the west coast in California in the immediate post-World War II era, and their proximity to Hollywood fashion designers lead to one of the clothing designs most associated with country music – the rhinestone western suit. Designers like Nathan Turk and Nudie Cohn had been creating wardrobes for western movie stars like Gene Autry and Tex Ritter for years, but the innovation of rhinestones and brash and bright colors insured the Maddox Brothers & Rose not only stood apart musically from other country and western bands in the nation, but now they could truly bill themselves as “America’s Most Colorful Hillbilly Band”! Soon performers such as Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, and Little Jimmy Dickens were knocking on Cohn’s door and “Nudie suits” became the most prominent form of country music stage attire of the mid-20th century.

Country music has always had an interesting way of presenting itself. From the mountaineer attire of the 1920s to the loud and bold Nudie suits of the 1950s – and all the other clothing-enhanced personas in between (think of Johnny Cash’s “The Man in Black” and Minnie Pearl, for instance) – country music has reflected elements of our own nation’s history: plaintive and nostalgic in the days of the Depression to excited and flashy in the post-war economic boom of the 1950s, and beyond. Perception has always played an important part in how the nation saw country music and how country musicians and record companies saw the nation. Country music and its attire has, and always will be, an important marker not only of who we are but the people who made us that way.