The history of old-time and hillbilly music, especially as it became popular in the years after the Bristol Sessions, is often marked by copyright questions: from murky provenance to songs written by one person and copyrighted by another, and everything in between. Many songwriters, especially those who were uneducated or illiterate, didn’t know how to copyright their songs or were woefully underpaid for their creations.

One such story centers on Dorsey Dixon, a North Carolina millworker who wrote and originally recorded the song later popularized by Roy Acuff as “Wreck on the Highway.” A pious, humble man who left school at 12 to work in a textile mill with his father and older siblings, Dixon “believed that his special mission in life was to spread the gospel through music,” as Patrick Huber tells us in his fascinating and award-winning book Linthead Stomp: The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South. (For those who want to learn more, Linthead Stomp is usually available in The Museum Store and features a full chapter about the Dixon Brothers.)

Although he had a clever and quirky sense of humor, which was showcased in his song “Intoxicated Rat,” most of Dixon’s songs, usually featuring his brother Howard too, are religious in nature or end with a moral. Many are also event songs – topical songs that focused on recent, often newsworthy, tragedies such as train wrecks or the sinking of the Titanic. Event songs were very commercially popular for hillbilly music. “The Wreck of the Virginian” and “The Newmarket Wreck” were two of these that were recorded at the Bristol Sessions, and “The Wreck of the Old 97” is probably the most enduring song of this genre.

Dorsey Dixon wrote numerous event songs, and he wrote his most successful one after witnessing a car crash outside East Rockingham, North Carolina, in 1937. The focus of “I Didn’t Hear Nobody Pray” was not the crash itself, but rather, as Huber relates, “the curious onlookers who only gawk at the twisted wreckage and bloody bodies instead of beseeching God to receive these souls.” Recorded in early 1938, the song resurfaced in 1942 when Grand Ole Opry star Roy Acuff recorded the song as “Wreck on the Highway” and it became a national sensation.

Acuff said that he had purchased the lyrics from someone in Knoxville and that Fred Rose, his music publishing partner, had written the music. In reality, the copyright was at the time jointly owned by Dorsey Dixon and Wade Mainer, a banjo player who had earlier convinced Dixon to register the copyright for the song in both their names, possibly for marketing reasons since Mainer was at that time a full-fledged radio star and his name would generate sales. It took four years but in 1946, under threat of a lawsuit, Dixon finally settled with Rose to begin receiving the royalties he deserved from the song. He spent $250 of the settlement to buy out Mainer’s share.

Dixon didn’t seem to hold onto any hard feelings towards those who had basically pirated his song; as Huber notes, Dixon even later wrote: “I’m certain the Lord worked through Acuff and Rose in my favor.” And like many artists of his day, he knew there was value in his musical output but didn’t fully understand how to take advantage of that value nor how to protect himself and his songs from others within the realms of copyright.

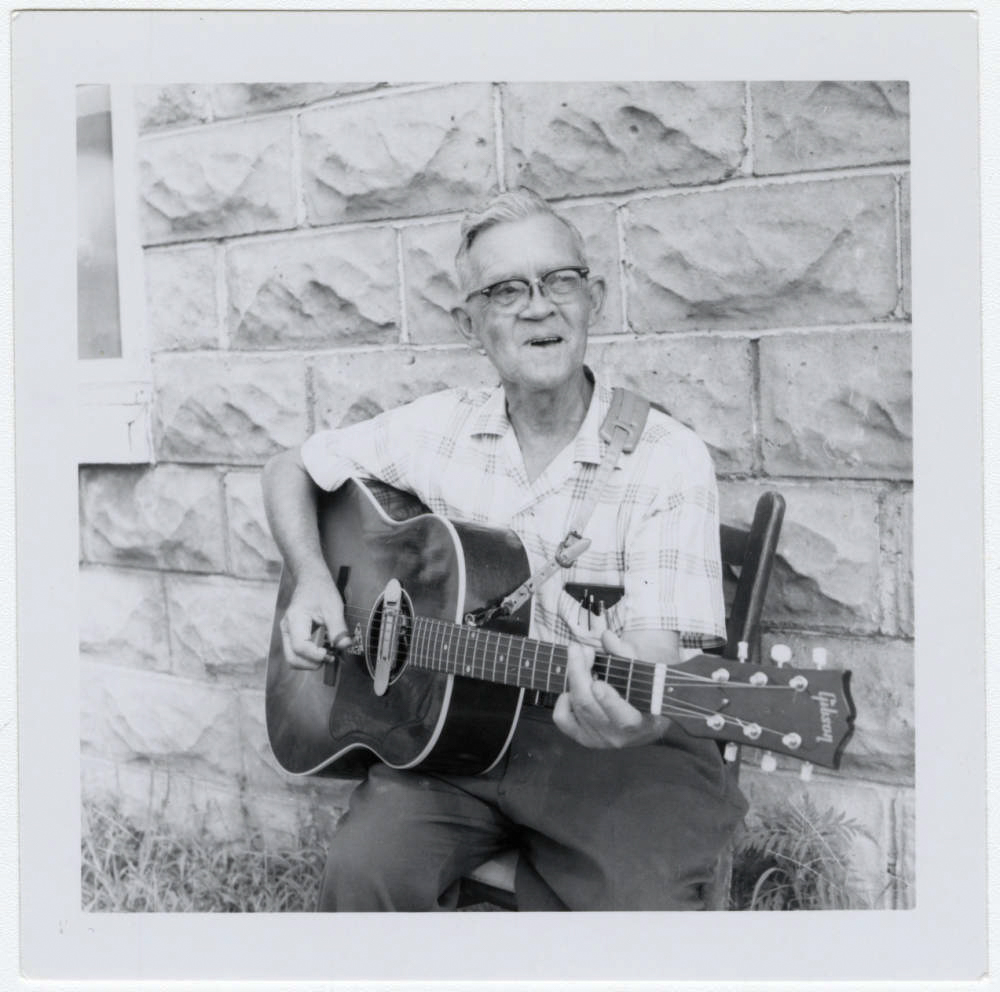

Dixon played very little in the 1940s and 1950s as he got older, but he experienced a brief renaissance in the folk revival of the mid-1960s. He played at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963, and in 1965 released his final album Babies in the Mill: Carolina Traditional, Industrial, Sacred Songs. It picked up a theme common in some of his earlier songs like “Weave Room Blues” and “Spinning Room Blues,” that of life in the North and South Carolina textile mills. He died three years later.

Dorsey Dixon didn’t become a national sensation. His songs though are a fascinating window into both the daily life of a working-class textile laborer and into the very soul of a devout Free Will Baptist who believed his songwriting would fulfill the “great purpose” for which he believed he was put on earth.

Guest blogger Joseph Vess lives in Meadowview, Virginia, where he listens to lots of old-time music and occasionally plays the guitar. He urges you to give the Dixon Brothers their due by enjoying the complete Dixon Brothers recordings, along with a 164-page book by Patrick Huber and extensive liner notes, available from Bear Family Records.