There have been many different forms of communication throughout history. One that has stood the test of time is postcards. Postcards typically have a picture on the front and space on the back to write a note and address the card to a loved one. While they are still used as a way to communicate, a lot of people, like myself, collect postcards as souvenirs from the places they visit. In 1945, the term deltiology was coined by Professor Rendell Rhoades and his colleagues at Ohio State University. Deltiology is the study and collection of postcards.

There is an Institute of American Deltiology located in my hometown of Myerstown, Pennsylvania, which is about 40 minutes east of Hershey (Yes, the chocolate town). The institute was established and is run by Donald Brown who began collecting postcards in 1943. The collection now contains over one million postcards that are preserved at the University of Maryland. I have been lucky enough to have visited and spend some time at the institute. Almost every room of the institute’s three story house is filled with postcards covering the whole state of Pennsylvania and the other 49 states of America. Today, vintage postcards are also used as a way to tell the history of a place. There are two book series – Images of America, and Postcard History – that use postcards as the basis of their history. Both series even have books on specifically about Bristol – Bristol to Knoxville: A Postcard Tour, Bristol (Postcard History: Tennessee)!

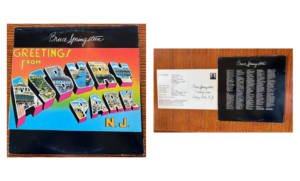

Historians are not the only people inspired by postcard artwork. Bruce Springsteen took inspiration from postcards for his Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. album cover. He used postcard art because he wanted it to be known that he was from New Jersey. Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. was Springsteens’s first studio album. It was released on January 5, 1973 and includes “Blinded By The Light.” Originally this album did not sell well and peaked at 60 on the Billboard charts. Now it is one of the most recognizable album covers. Springsteen’s Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. album cover shows that postcards have a much bigger impact on culture than just a way to communicate. Springsteen is not the only artist to use postcards as inspiration. There are countless songs, lyrics, and covers across all music genres that have used postcards as inspiration.

Within the museum’s collection we have several historic postcards of downtown Bristol. This one of State Street was purchased by the museum in 2019. The postage mark notes that it was mailed on August 30, 1937 in Portland, Oregon. The postcard was printed by Asheville Post Card Company out of Ashville, North Carolina and the image was colored by C.T. American Art Colored, which is also known as Curt Teich & Co.

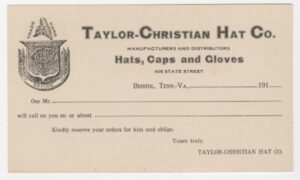

This postcard in the museum’s collection is from the Taylor Christian Hat Company. The 1927 Bristol Sessions were recorded on the second floor of the hat company’s storefront. Instead of a photo postcard this one addresses an order from a customer. This postcard is one of the only artifacts that document the business of the Taylor Christian Hat Company and where the building was located as it is no longer standing in downtown Bristol.

Lastly, this postcard was donated by the descendants of Alfred Karnes. Karnes recorded 6 songs at the 1927 Bristol Sessions. The postcard depicts the Bayless Highway Baptist Church located near Starke, Florida. This church was one of the last places where Karnes’ preached before he passed away in 1958.

In addition to these postcards from the vault we have several postcards on display near the virtual postcard kiosk where you can send a digital postcard to a loved one when you visit the museum!

By Julia Underkoffler, Collection Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.