I believe in the power of collaboration, a constant factor in the long process of bringing the Birthplace of Country Music Museum to life and to its grand opening in 2014.

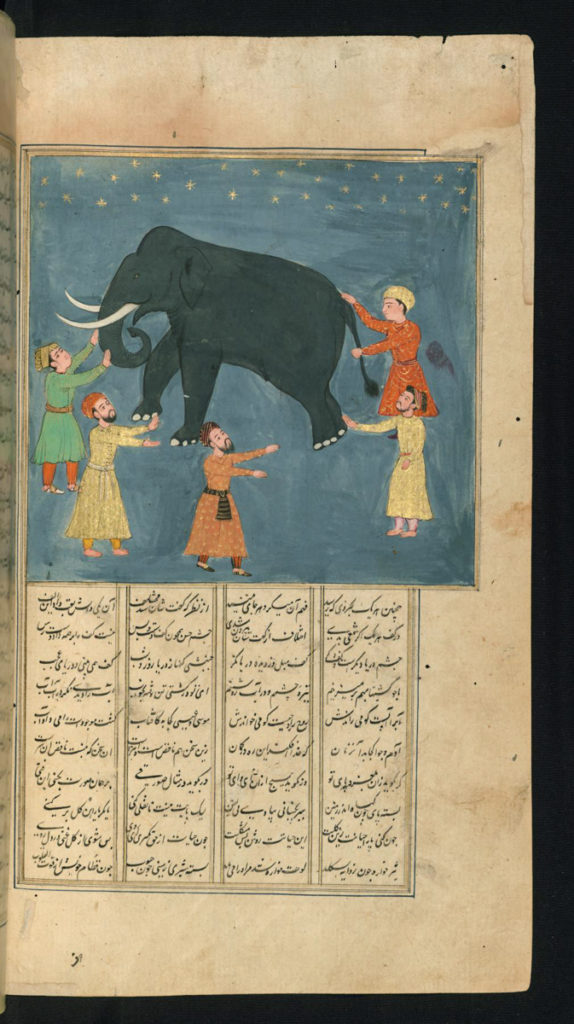

Recently a segment I heard on an NPR program caught my attention and got me thinking again about collaboration. I must have been listening “out of one ear,” because I can’t remember the topic of the segment. What I do recall is the parable the speaker employed to illustrate his topic. It involves a group of men describing an elephant by touch in a dark room, although even here my memory is muddled. So I have turned to Google (as one does) for help. It turns out that there are many versions of the parable, but a poem by Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet, scholar, and mystic is closest to the story paraphrased on NPR.

Here is Rumi’s poem, as translated by Coleman Barks:

Elephant in the Dark

Some Hindus have an elephant to show.

No one here has ever seen an elephant.

They bring it at night to a dark room.

One by one, we go in the dark and come out

saying how we experience the animal.

One of us happens to touch the trunk.

“A water pipe kind of creature.”

Another, the ear. “A very strong, always moving

Back and forth, fan-animal.”

Another, the leg. “I find it still,

like a column on a temple.”

Another touches the curved back.

“A leathery throne.”

Another, the cleverest, feels the tusk.

“A rounded sword made of porcelain.”

He’s proud of his description.

Each of us touches one place

and understands the whole in that way.

The palm and the fingers feeling in the dark are

how the senses explore the reality of the elephant.

If each of us held a candle there,

and if we went in together,

we could see it.

The elephant identification story predates Rumi by millennia, and occurs in many variations, cultures, and religions, but the moral is similar in all versions. According to Wikipedia, “at various times the parable has provided insight into the relativism, opaqueness, or inexpressible nature of truth, the behavior of experts in fields where there is a deficit or inaccessibility of information, the need for communication, and respect for different perspectives.”

In my decades as an architect, I have valued the principles of open-mindedness, good communication, and the certainty that there are more ways than one to solve a problem. These principles are the essence of collaboration.

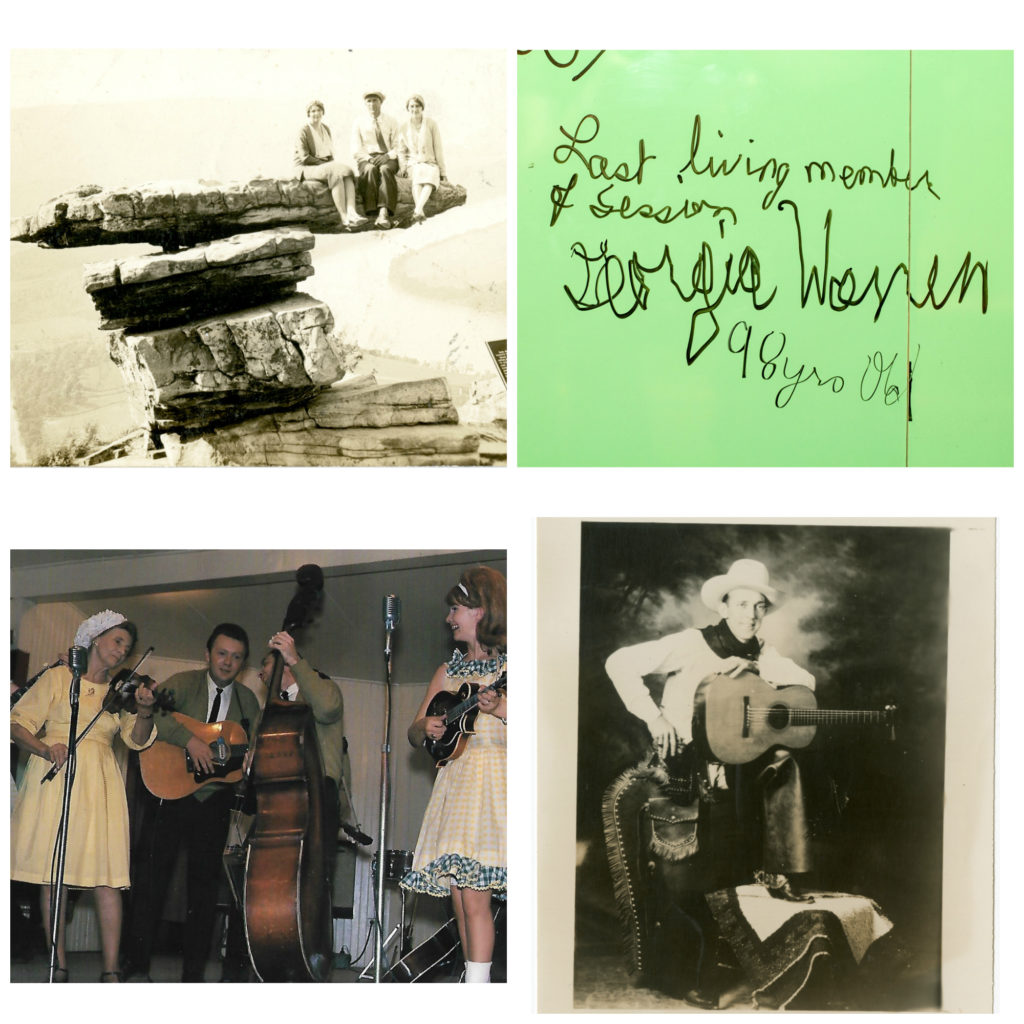

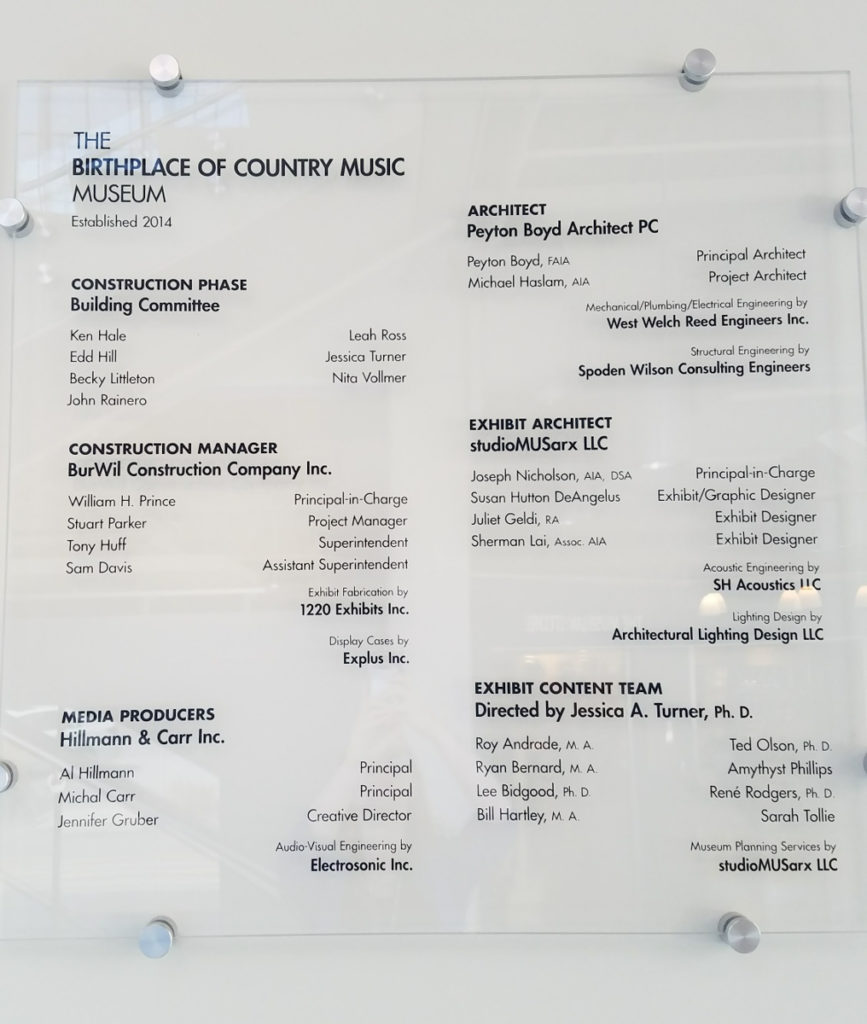

My firm had the privilege of working with a remarkable “brain trust” assembled by the Birthplace of Country Music to help bring the museum to fruition. A plaque in the museum lobby recognizes these creative individuals and firms, each contributing in their own way to the whole. In addition to an exhibit content team of musicologists, academics, and musicians, the group included exhibit designers and museum planners, lighting and acoustical consultants, media producers, and the construction manager. Each of these was on a mission to make their particular area of influence the best it could be, and each knew that the realities of budget, scheduling, space limitations, historic preservation, and other constraints would require concessions and cooperation. These interactions were the norm, not the exception. We spent a lot of time talking and planning, debating different points, sometimes disagreeing, but always finding the best path together.

A few of those collaborative efforts, visible now to our visitors and central to their experience, come to mind. For instance, in an early design concept, the area outside of the Orientation Theater in the upstairs atrium was conceived as a front porch in a rural setting. However, as the content team developed the “story” to be told by the museum, the romantic notion of a hillbilly strumming a guitar on a cabin porch gave way to something more related to 1920s Bristol: a train station setting. We gave exhibit architect Joe Nicholson of studioMUSarx a tour of the Bristol Train Station, which was built in 1902 and in use in the 1920s, and worked with his design team to style the space as a passenger waiting room, with references to the materials and details found in our local landmark. This space illustrates the mode of travel for some of those who participated in the 1927 Bristol Sessions, but it also acts as a marker to tell the wider context of the recording sessions that came before those held in Bristol.

Another great example is the wood that was used in various areas in the museum. Several years before we began our detailed design work, a local purveyor of curly maple used in solid body guitars (Gibson guitars, in fact!) offered a gift of “seconds” of this wood for use in the museum. Fortunately, his offer was still on the table when we began to specify finish materials, and there was enough material for flooring in The Museum Store. Architect Michael Haslam, my former associate, developed a scheme to use curly maple and other “tone woods” – species used in the creation of musical instruments such as walnut or ash – for flooring and other finishes throughout the museum. While on the outside this design may just look attractive, the connection to woods used for musical instruments means that these details have deeper meaning, and our visitors are always interested to hear about these elements in the museum design.

The chapel setting in the permanent exhibits was originally conceived as a trompe l’oeil interior where a video projection created the illusion of a larger interior space showing congregants seated in rows facing a group of shape-note singers. A single pew would provide limited seating for museum visitors at the back of the setting. Two elements of the chapel design changed as the content conversations developed: the film and the setting. The creation of the film didn’t just involve filming the groups performing gospel and sacred music – the artists also shared their thoughts about how this music expresses and celebrates their belief in God, an important parallel to the sacred songs of the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Some of the artists, such as the New Harvest Brothers, also sat in on meetings once filming had ended to help us shape the film and its focus – a true collaborative effort. We wanted to share the voices of the musicians who are performing in this gospel tradition today in a respectful way and give them the opportunity to tell the story of their faith and music.

The chapel setting also changed. First, it evolved from a virtual space to a “real” one. The church that comes to mind for most people when they think about traditional sacred music is a small, white clapboard church with a steeple. There are many wonderful churches of this type in Appalachia. But this is not the only type of church architecture found in this area, and when we looked at some of the churches associated with different Bristol Sessions artists, we found a brick model that worked well for our exhibit. The Tennessee Mountaineers, a group made up of a church congregation, didn’t have their own home church at the time of the Sessions, but they later built a small brick church in Erwin, Tennessee, patterned after a brick church seen in Bristol, and it is that church that inspired the design of the museum’s small chapel exhibit. A serendipitous find by a member of the exhibit design team also resulted in the donation of antique church pews. One round trip to Philadelphia later, the pews were in Bristol ready for refurbishing, and once finished, the acoustic designer placed speakers under the pew seats to provide a physical as well as aural sensation from the soundtrack on the video.

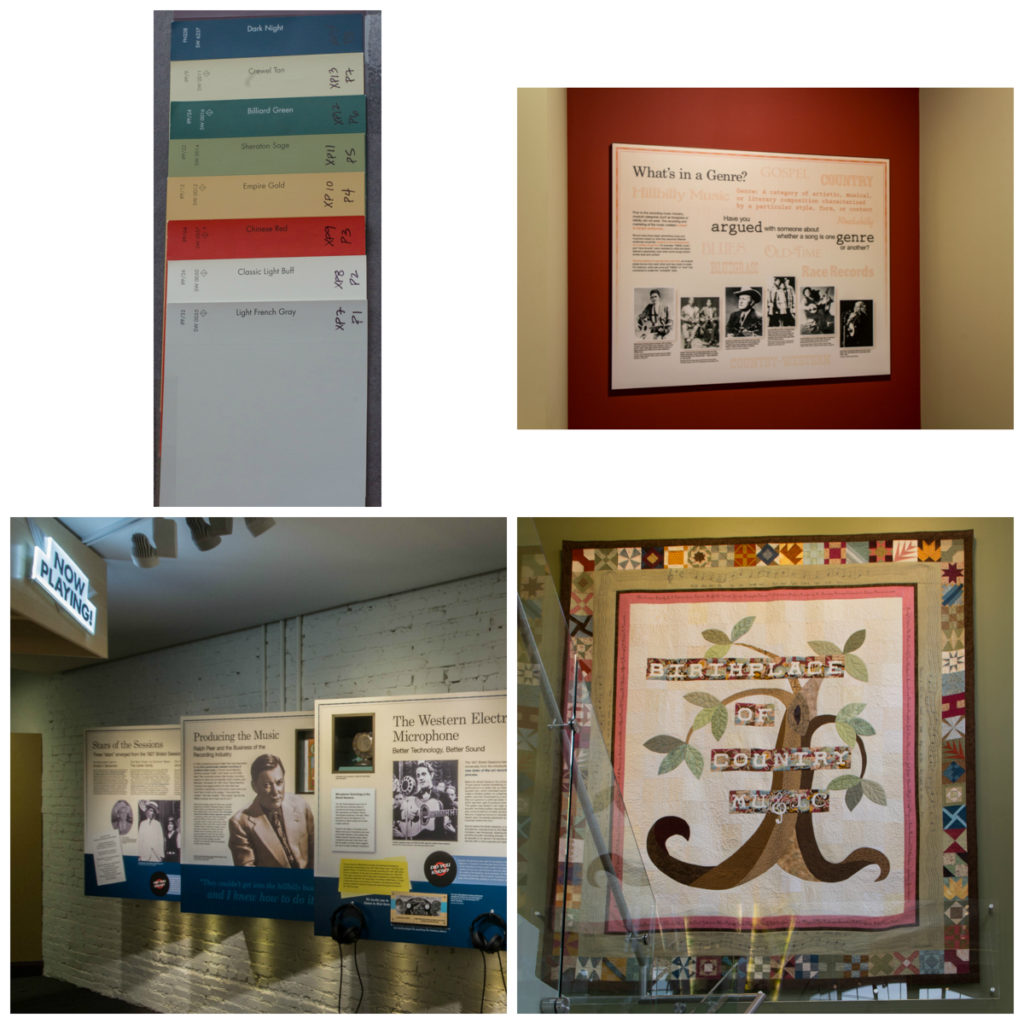

Another great detail, again pulled together after much discussion amongst the team, is the coordinated color scheme used throughout the museum. Developed by the exhibit designers for graphics, panels, and other exhibit components, the color scheme used for walls and other architectural elements was inspired by the ideas of home and comfort, an important facet of the lives of the 1927 musicians and their audience. The designer turned to reference images on American quilt making, seeing many quilts with amazing colors made from the fabrics related to the clothes, blankets, and meals (flour sacks with labels, etc.) of these quilt makers. From these connections to the past, she was able to create a color palette for use in the museum that addressed the needs of the architectural spaces in harmony with the exhibits. The Bristol TN/VA Chapter of the Embroiderers’ Guild of America also successfully employed the colors for the thread and fabrics in the beautifully crafted quilt that graces the main stairway, again tying the small details together.

There are many more examples of fortuitous collaboration that helped create the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, and we are grateful to hear from our visitors every day that this hard work produced an amazing experience for the eyes, ears and heart. And we are grateful for the experience of working together as a team on such an interesting project. As Joe Nicholson said: “We really ended up with a seamless integration of the building with the exhibits and full owner participation throughout. I wish I could do one of these projects every year!” I couldn’t agree more.