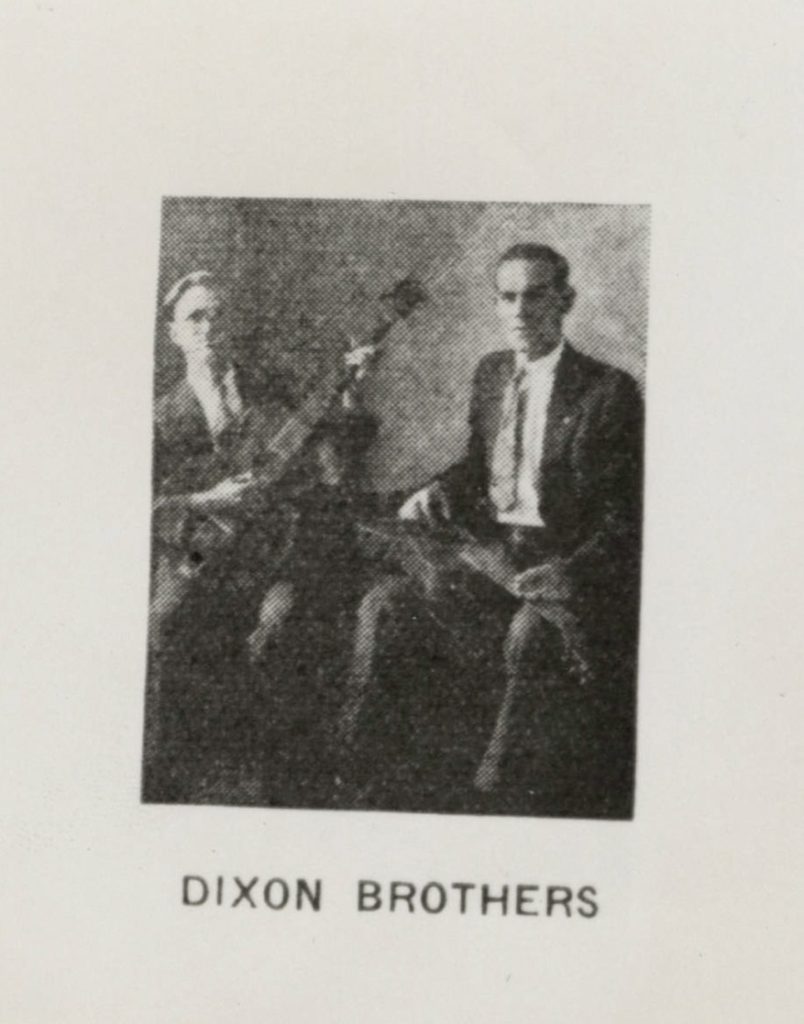

On February 9, 1889, Norman Edmonds was born in Wythe County, Virginia. Edmonds recorded four songs at the 1927 Bristol Sessions, playing fiddle alongside J. P. Nester’s singing and banjo on “Train on the Island,” “Black-Eyed Susie,” John, My Lover,” and “Georgia.” Their version of “Train on the Island” was included on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Music in 1952.

Only two sides from the Sessions recordings were released (“Train on the Island” and “Black-Eyed Susie”), but Ralph Peer was impressed with their sound, a wonderful throwback to earlier stringbands that were made up of just fiddle and banjo together. Peer invited them up to New York City – all expenses paid – to record further; however, Nester refused to leave his Blue Ridge Mountains home and so a continuation of their partnership “on record” didn’t happen.

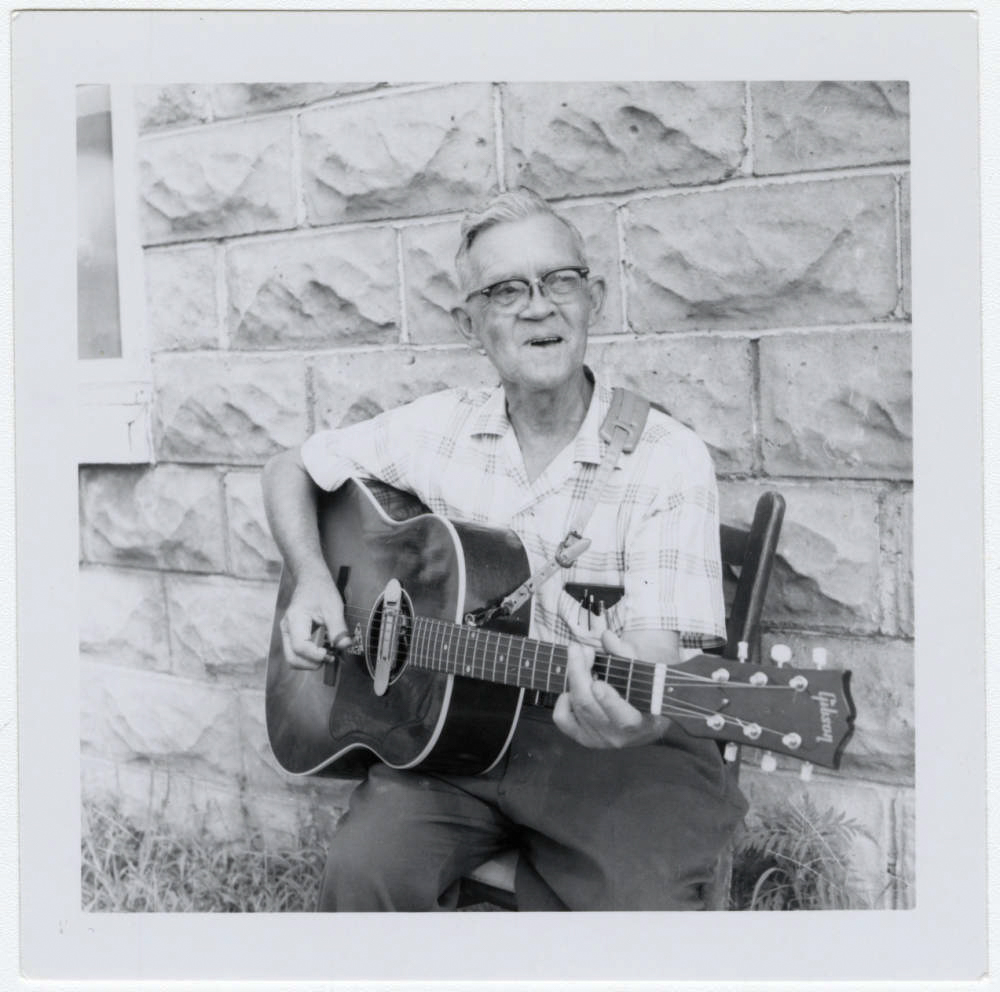

Edmonds, who played the fiddle in the “old-time” way, where he held it against his chest rather than underneath his chin, may not have gotten another chance to record in the 1920s and 1930s, but his fame as a fiddler saw him become a local star in his later years. He performed at the Galax Old Fiddler’s Convention (amongst others), played on several LPs made in Galax and also one for independent label Davis Unlimited, and had his very own radio show called The Old Timers.

As with so many traditional musicians, whose music and instruments were passed down through the generations, Edmonds learned his playing from his father, who learned it from his father. And today, Edmonds’ grandson Jimmy Edmonds of Galax, Virginia, has also come to music and instrument building the old-fashioned way: through his family. He is a 5th-generation Edmonds fiddle player – he started playing at four years old, picking up other instruments along the way – and his father was a luthier who passed on his skills, tools, and craftsmanship to his son. Jimmy started off helping his father repair instruments and working on finishes, moving on to making his first fiddle under the encouragement of luthiers Wayne Henderson and Gerald Anderson. A busted Wayne Henderson guitar while he worked at the Myrtle Beach Opry led to guitar building.

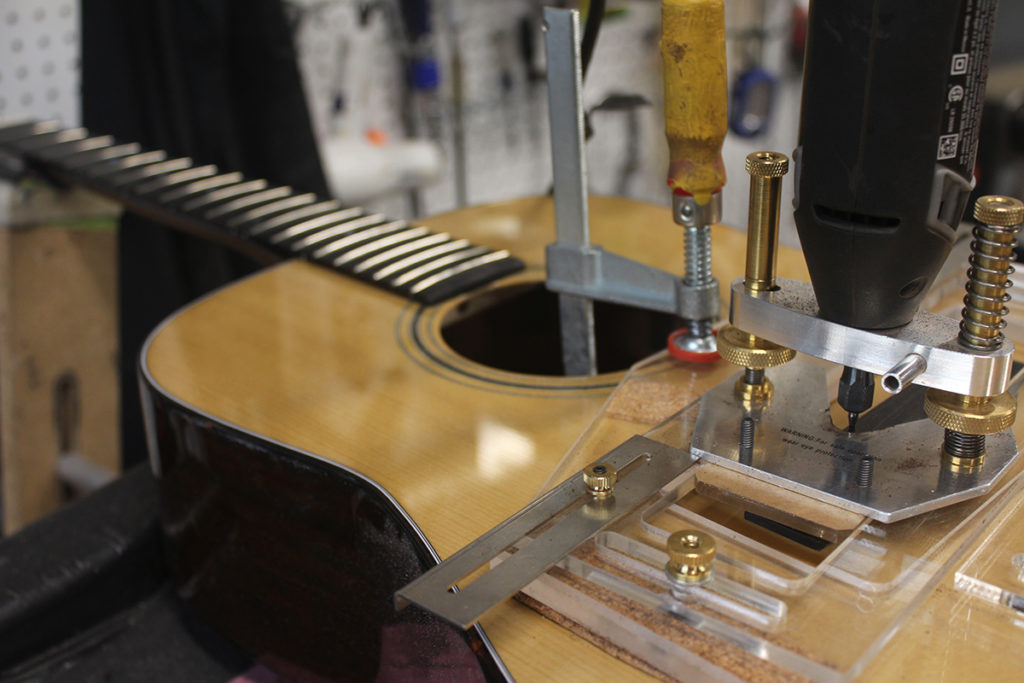

The legacy of this mountain music, and the craft that makes it possible, is wonderfully on display through Jimmy’s work. A visit to Jimmy’s workshop gives you a real insight into the traditions that come together when luthiers make their instruments – the choices of wood, the techniques used, the influences from past luthiers and the innovations of present-day ones, the decorative touches that hold meaning and beauty. And it gives you the chance to see the huge amount of work, love, and care that goes into crafting each and every instrument, and why those who are lucky enough to own an instrument by Edmonds are pretty passionate about them! This video from a February 2013 Fretboard Journal article serves as a great introduction to Jimmy’s work:

Jimmy mostly makes guitars – he is almost to his 300th guitar – but he also makes fiddles, mandolins, Dobros, and dulcimers, and he helps with the fretwork, pearl inlay, and the finish on his workshop partner Kevin Fore’s banjos. He does not copy any set style or type of guitar, but he is a big fan of 1930s and 1940s Martin guitars and therefore many of his builds reflect those iconic instruments. He has crafted some of his own innovations and decorative touches in the guitars he builds. Henderson views Jimmy’s finish work as some of the best out there – he uses varnish rather than lacquer – and he often does the finish work on Henderson’s guitars.

The passing down of tradition amongst families and from luthier to apprentice is what keeps this craft and this music alive. And so today, we celebrate that passing on from grandfather to grandson, and from father to son, as an appropriate way to mark the anniversary of Norman Edmonds’ birth!

Jimmy Edmonds is featured in our current special exhibit The Luthier’s Craft: Instrument Making Traditions of the Blue Ridge. The exhibit is open through March 4, 2018. He is also a member of the Virginia Luthiers, alongside other luthier band members Wayne Henderson, Gerald Anderson, and Spencer Strickland.