Voice Magazine for Women, a free, monthly publication distributed regionally in Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia to 650 locations, partners with the Birthplace of Country Music an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, to take you inside the special exhibit I’ve Endured: Women Old-Time Music, on display at the museum through December 31, 2023. Each month through the duration of the exhibit, Voice features impactful stories of the hidden heroines, activists, and commercial success stories of the women who laid the foundation for country music. Inspiring, insightful, and Dolly-approved, you may just find a piece of yourselves, or a loved one, in the stories of some of these hidden figures in American music.

With their permission, we have duplicated our “I’ve Endured: Woman in Old-Time Music” special feature article for this month – we hope you enjoy it! To read this month’s issue in its entirety, click here.

The Stories of I’ve Endured: Women in Old-Time Music

Etta Baker

By Guest Contributor Charlene Tipton Baker

“Etta Baker didn’t put up with any of that foolishness, either. You know, she would call somebody on it. She’d say ‘Lord, honey, I have been around so long, how could you call me a girl?” ~ Sheila Kay Adams, Appalachian ballad singer

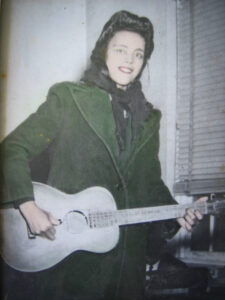

Born in 1913 in Caldwell County, North Carolina, Etta Baker learned how to play guitar before she could hold one. She grew up in a musical household, with influences passed down from her African American, Irish, and Native American lineage. When she was just shy of three years old, her dad would lay his guitar on a bed face up as she stood, teaching her tiny hands how to pluck the strings and work the frets.

It was around that time her family moved to Keysville, Virginia. She would often get up in the middle of the night to listen to her dad play, and she played music at churches, parties, and dances with her family as a child and young woman. In interviews she has said that she practiced on her guitar an hour or more every single day. The music she made brought her great joy and, while sleeping, Etta often dreamed of the melodies she would write. She played 6-string and 12-string guitar and the 5-string banjo. The majority of Etta’s songs were instrumental; she chose instead to let the chords and melodies of her instrument do the talking.

Married at the age of 36 to a piano player, Etta’s husband forbade her to play music outside the confines of the home. Decades would pass before Baker was given the opportunity to perform her music in public again, so she helped make ends meet working in a textile factory. Together they had nine children and she played for her kids and encouraged their musical abilities. When asked how she had time to play music with so many children, she laughed and replied “I made them be quiet!”

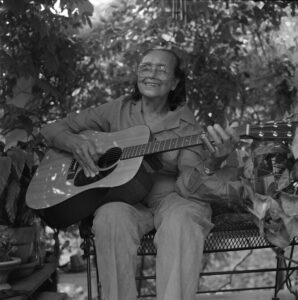

Baker’s distinct, two-finger style of picking the Piedmont blues would later influence artists like Bob Dylan, Taj Mahal, and Kenny Wayne Shepherd, but she never achieved the money or the fame she so deserved—an all too familiar narrative around the careers of many women in early American music.

“This gracious grandmother was the source of a great deal of joy and surprise when I found that she still played guitar after I had heard her early recordings in the ’60s,” says blues legend Taj Mahal. “One of the signature chords of my guitar vocabulary comes from her version of ‘Railroad Bill.’ This was the first guitar-picking style that I ever learned.”

In fact, Etta was 43 years old before she was “discovered” by renowned folk singer and scholar Paul Clayton who, along with Diane Hamilton and Liam Chancey, recorded and released five of her songs on the compilation album Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians. Those historically significant recordings were among the first commercial releases of African American banjo music, and though Etta’s songs “One Dime Blues” and “Railroad Bill” became traditional standards, she was unpaid for the session.

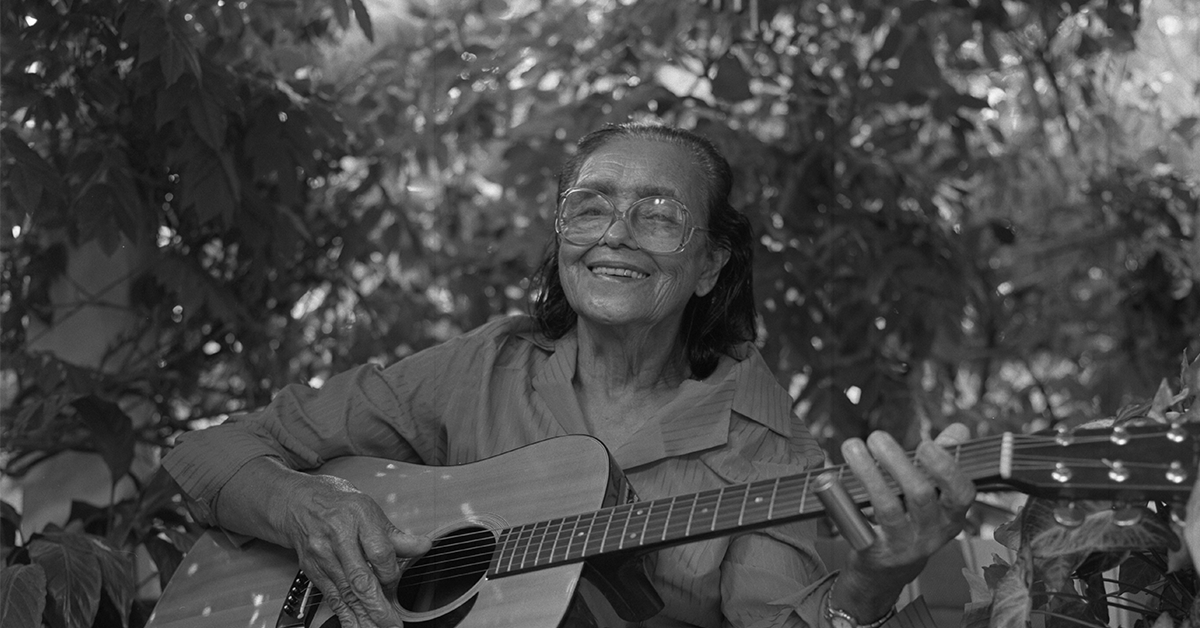

Baker was invited to perform at the 1958 Newport Folk Festival due to the impact of those recordings, but was denied the opportunity by her husband. After he passed away in 1967, she left her job to pursue music full time. In 1991, at the age of 78, Etta released her first album, One Dime Blues, on Rounder Records. She soon became recognized as one of the foremost practitioners of the Piedmont finger-picking style—her right forefinger picking out melodies as the thumb strummed the bass notes.

Decades passed before Etta was able to regain the rights to those early recordings, doing so with the help of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, a North Carolina-based nonprofit that provides traditional musicians 55 years and older with financial and professional support for their art.

Whatever hardship or challenge Baker may have endured over her long life, she remained positive and focused on playing the music passed on to her by her father and his family before him. She also loved to garden, grow and can her own food, and forage for herbs. She had many grandchildren and also loved playing music for them.

“Just the sound of happiness,” Etta said in a recorded interview for Music Maker. “It gets on your mind heavier than your ailments do, I think.” It must have been a healing kind of magic; in the same interview Etta proclaimed she never knew any doctors or treatments until she was 89 years of age.

In 1991 Etta was honored with a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts after winning the North Carolina Folk Heritage Award from the North Carolina Arts Council two years prior. The wunderkind passed away in 2006 at the age of 93, having performed music into her 90s.

Etta Baker possessed a soul that breathed the essence of music, transcending the ephemeral allure of fortune and fame. With each pluck and strum, her hands were vessels, channeling the sounds of her ancestors. Her guitar was an extension of her very being, an instrument of liberation and expression. Her legacy transcends the trappings of success, forever embodying the boundless joy of music for music’s sake. Her enduring legacy serves as an inspiration for women and musicians of all ages, showcasing the unwavering passion and dedication that can carry an artist through a lifetime of creating and sharing their art.

Stay tuned! Next month’s I’ve Endured: Women in Old-Time Music spotlight will focus on the dynamic performer, musician, and forward-thinking businessperson Cousin Emmy, born Cynthia Mae Carver, the first woman to take home a win from the National Old Time Fiddler’s Contest, and a teacher and influencer to Hee Haw’s Grandpa Jones. She also appeared in Hollywood films and on television.