Each year February is highlighted as Black History Month. This call to recognize the central role of African Americans in our history was first put forward by Dr. Carter Goodwin Woodson in 1926. As a blog post on the National Museum of American History website notes: “When mainstream history either largely ignored or debased the Black presence in the American narrative, Dr. Woodson labored to inject a fair portrayal of African Americans into the national record.”

At first glance, you might not think that the history of early country music intersects a great deal with African American history. However, the intersections exist and are significant, and we’ve explored some of these in the Birthplace of Country Music Museum – for example, in the development of genre, with musicians who had impact on early commercial country music, and of course, through the African origins of the banjo, an instrument now indelibly linked to country and bluegrass music. And there has been a continuing presence of African Americans in country music beyond the early commercial years, for instance with artists like DeFord Bailey, Charley Pride, Linda Martell, and the celebration of black stringband music by the Carolina Chocolate Drops. Books like Diane Pecknold’s Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music and Francesca Royster’s Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions explore these connections more deeply.

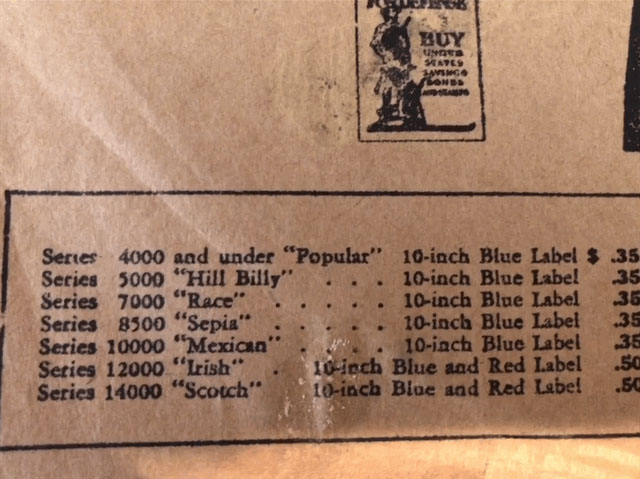

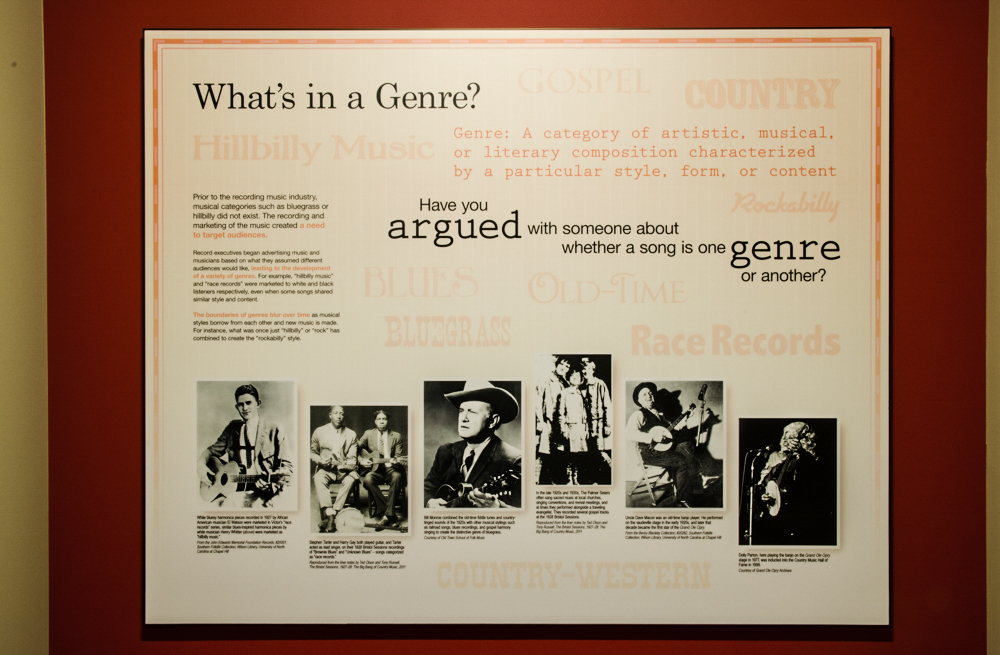

Prior to the recording music industry, musical categories such as blues or rock or country did not really exist. However, the recording and marketing of music created a need to target audiences in order to make money, and so record executives began advertising music and musicians based on what they assumed different audiences would like, leading to the development of a variety of genres.

One of these genres was known as “race records,” commercial recordings that were aimed specifically at African American audiences. Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” produced by OKeh Records in 1920, was one of the first recordings in this new genre. Selling around 8,000 copies per week over several months, the popularity of “Crazy Blues” proved to record executives that there was a market and an audience for “race records.” Companies began developing catalogues aimed at these audiences, and they often hired black talent scouts and agents to find musicians to record. Much of these early recordings were focused on blues artists.

Despite the seeming segregation of audiences – with black audiences targeted through “race records” and “hillbilly records” marketed to white audiences – the lines between genres were often crossed with musicians, styles, and songs from each influencing the other. And, of course, just because a record was marketed to a particular audience doesn’t mean that other audiences didn’t listen to and buy that record.

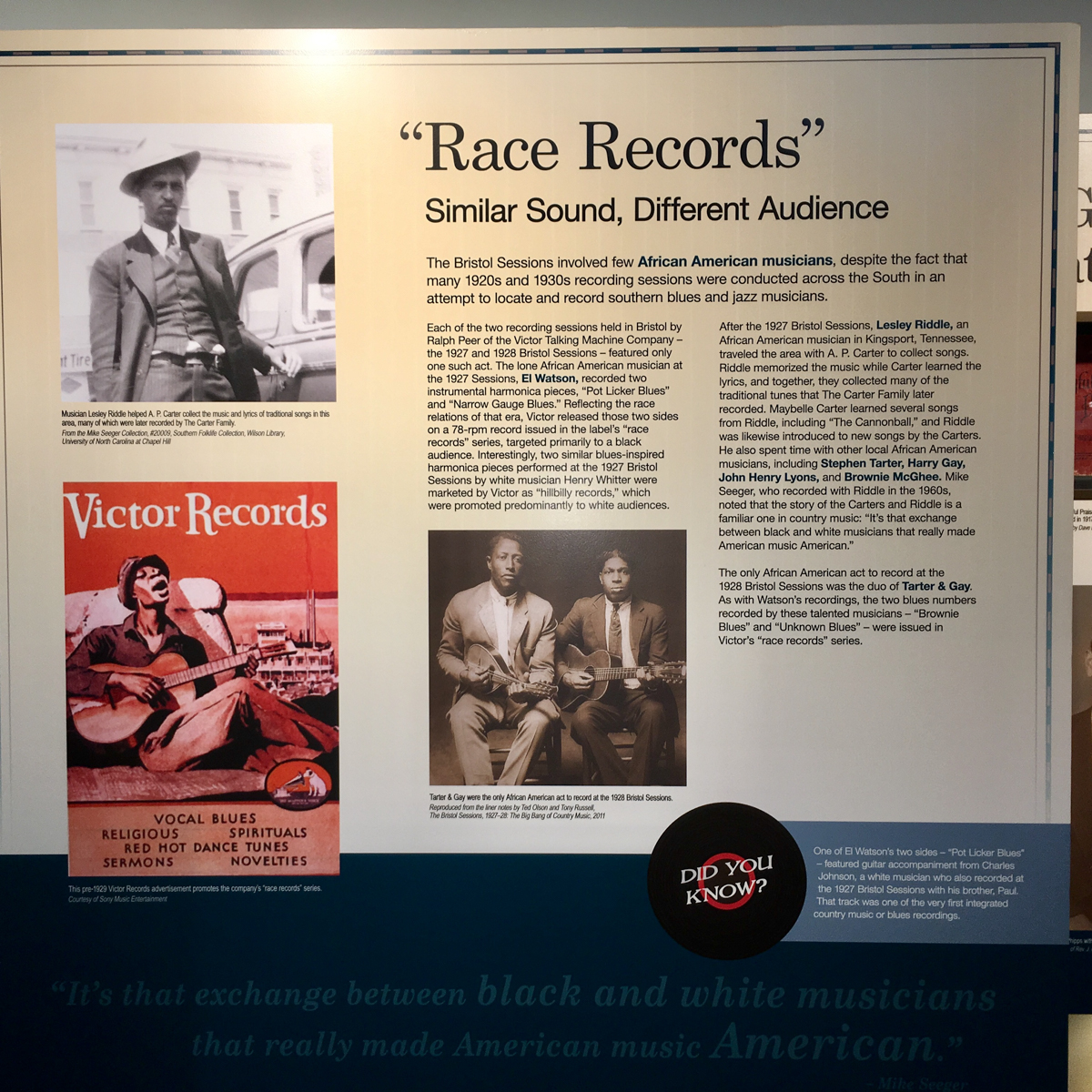

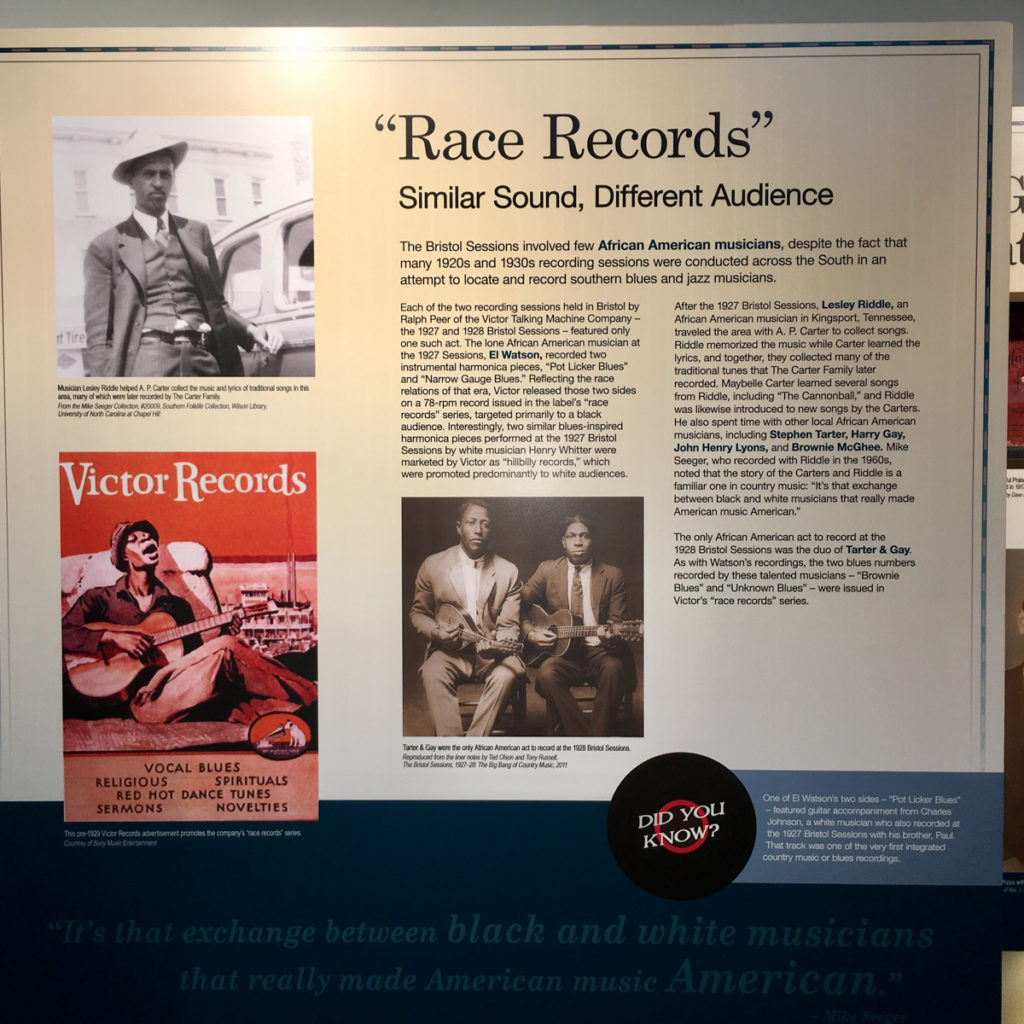

The Bristol Sessions involved few African American musicians. Each of the two Bristol recording sessions held by Ralph Peer of the Victor Talking Machine Company – the 1927 and 1928 Bristol Sessions – featured only one such act. At the 1927 Sessions, El Watson recorded two instrumental harmonica pieces, “Pot Licker Blues” and “Narrow Gauge Blues.” The fairly arbitrary categorization of genre is reflected in the marketing of Watson’s recordings – Victor released Watson’s two sides in the label’s “race records” series, while two similar blues-inspired harmonica pieces by white musician Henry Whitter were marketed as “hillbilly records” and promoted predominantly to white audiences. Watson also played the bones on some Johnson Brothers (a white duo) recordings at the 1927 Bristol Sessions, and Charles Johnson played guitar on Watson’s sides; these are some of the earliest integrated recordings of country and blues music. There is little information about El Watson to be found in the historical record, but we do know that Peer was very much impressed by Watson’s sound and musical skills, inviting him to record four more songs with Victor in New York: “Fox Chase,” “Sweet Bunch of Daisies,” “Bay Rum Blues,” and “One Sock Blues.” It’s also likely that he recorded with Columbia Records in Johnson City, Tennessee, in 1928.

The duo of Tarter & Gay recorded the next year at the 1928 Bristol Sessions. As with Watson’s recordings, the two numbers recorded by these talented musicians – “Brownie Blues” and “Unknown Blues” – were also issued in Victor’s “race records” series. Before they recorded in Bristol, Stephen Tarter and Harry Gay had performed live for white and black audiences at dances, and the style reflected on their Bristol Sessions recordings touches upon ragtime and stringband music, amongst others.

And then, of course, there’s Lesley Riddle, a hugely influential musician who worked closely with A. P. Carter in his search for songs and music worth playing and turning into hits. And don’t forget: Riddle has also been credited with sharing his style of guitar picking with Maybelle Carter, who built on this learning with the now well known and revered Carter scratch. His significance to the history of early commercial country music cannot be overstated – you can read all about his impact and influence in our blog post here and here.

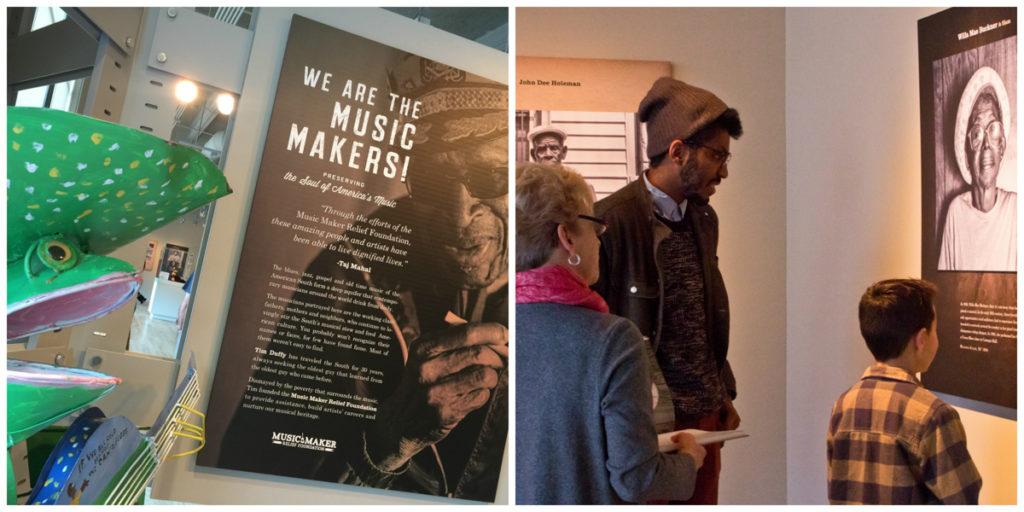

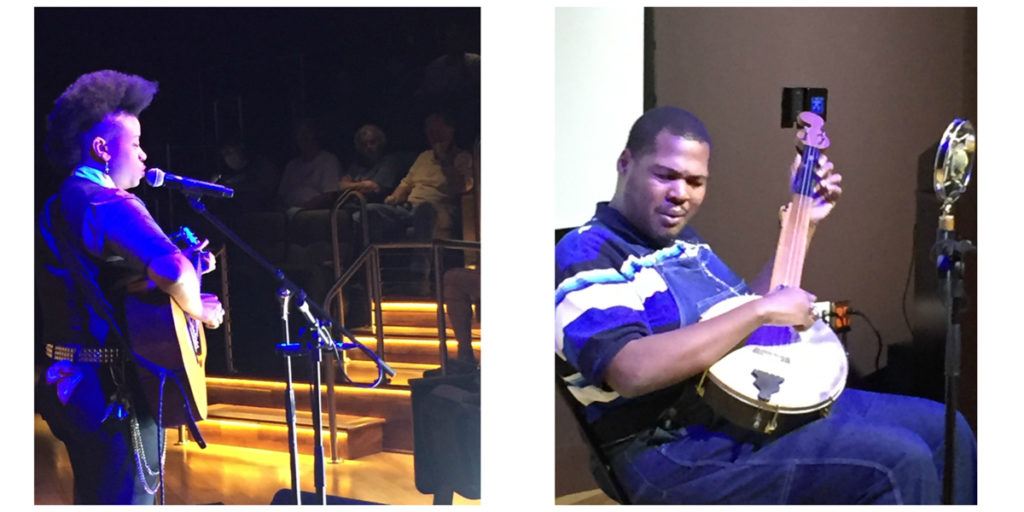

While Black History Month may be a starting point for talking about African American history in early country music, it is not the stopping point. This is why we have worked to share relevant content within the museum’s permanent exhibits and also to continue the conversation through special exhibits and public programming outside of this one month of the year – for example, the special exhibit We are the Music Makers: Preserving the Soul of American Music in 2016, our display of the Smithsonian poster exhibit A Place for All People, the live simulcast of the opening ceremony for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a roundtable discussion about the history of the local African American community, and engaging performances by a host of artists. to name a few.

Today there are criticisms aimed at setting aside a month or a week or a day of the year to commemorate important historical subjects – for instance, the question of whether setting aside a designated time to explore those histories means that they aren’t fully integrated into the study and understanding of American history. While in some ways the name of our museum – the Birthplace of Country Music Museum – might seem to narrow our focus, through exhibits, programming, and even collections we have tried to bring together the histories and voices of a variety of musicians and communities in order to underline just how much American music has been built and created from the intersection of different styles, different stories, different artists, and different backgrounds.